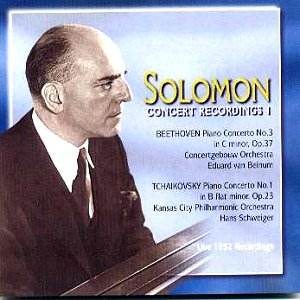

This is the first volume in a series devoted to live

Solomon performances and will fill his many admirers with anticipation

and enthusiasm. That the two concert performances here replicate two

of his best-known interpretations need not come as a disappointment.

Solomon recorded both the Beethoven C minor and the Tchaikovsky B flat

twice; the former with Boult in 1944 and Menges in 1956, the Tchaikovsky

with Harty in 1929, one of his first recordings, and again in 1949 with

Issay Dobrowen. These live performances date from a period of intense

travel, the Tchaikovsky, in Kansas, from the beginning of 1952 and the

Beethoven, recorded in Amsterdam, from the end; book-ending assiduous

and ceaseless performing.

The Beethoven is in good sound; it opens without particular

opulence but there is depth in bass sonorities and a just balance between

soloist and orchestra. There are some signs of a bronchial Dutch audience

but these are part of the on-the-wing performance. There are some little

differences between the now-three extant performances Solomon has left

us. In all three recordings his approach to the finale was essentially

stable; in the slow movement there is little difference in tempo between

van Beinum and Boult though with Herbert Menges (himself a pianist)

Solomon expands more. In the Allegro con brio his van Beinum and Menges

timings are almost identical; Boult was somewhat fleeter and inclined

to drive faster, inflecting the opening orchestral introduction, for

example, with myriad felicities. In Amsterdam there is sovereign clarity

in passagework in the opening movement. Dramatic and purposeful, there

is splendid unanimity between soloist and conductor with Solomon’s patrician

refinement as ever a thing of wonder. His control of dynamic contrast

and colouristic acumen are imperishable features of a thoroughly convincing

first movement. As was invariably the case he plays the Clara Schumann

cadenza. The Largo unfolds with measureless generosity. The Concertgebouw

woodwinds are on especially expressive form – the principal flute particularly

so – and van Beinum shapes the movement with real understanding (there

are a couple of scratches on the acetate in this movement but they are

of very little account). The tonal weight Solomon employs and his shades

of chordal colour and depth are as impressive as the way in which van

Beinum lightens string tone, where earlier the basses and cellos had

been strong and expressive. The finale goes with easy fluency, variegations

of tone and perfectly animated runs coalescing with the quietly humorous

spirit Solomon always engendered here. The close is brilliantly spirited

and well deserves the animated applause that night in Amsterdam.

The Tchaikovsky is, as Bryan Crimp justly notes, a

more outward-going and obviously virtuosic performance than the magisterial

1929 and 1949 commercial traversals. That said there is no trace of

ostentation or vulgarity here. Instead there is dashing technique in

the first movement with plenty of panache. The Kansas woodwinds certainly

pipe up strongly in this movement and one can savour the adrenalin rush

that Solomon could impart, from 7.00 onwards. Incendiary stuff. The

Prestissimo section of the Andantino semplice is rippling and deliciously

fleet, the return to the tempo primo negotiated well. It’s true that

the Kansas City orchestra is not the finest and also that there is some

congestion in the sound here and there but nothing enough to spoil pleasure

in Solomon’s drive and conviction. When it comes to the finale he does

drop one or two notes but this is heat of the moment playing even at

his accustomed tempo and nothing derails him from a triumphant conclusion.

The documentation is excellent and Crimp’s notes succinct.

We can look forward with confidence to the second volume of this series.

Both Brahms Concertos exist in off-air performances and it would be

good to hear Solomon’s speaking voice – he was recorded in interviews

on tour. Admirers await the next instalment with keen interest.

Jonathan Woolf