It is difficult for us to understand what actually

goes on in a police state dictatorship. Prokofiev had fled to the West

at the beginning of the Russian Revolution and had had many successes—and

a few failures. When he returned to Russia in 1933, it was the result

of a personal deal he made with Stalin, and Stalin, for all his many

failures and vices, kept that compact till his death in 1953 (Prokofiev

died the same day). We now realise that Prokofiev wrote whatever he

wanted to in Russia. The Party functionaries could challenge him but

Prokofiev thumbed his nose at them and they couldn’t hurt him. The closest

they got to him was when Prokofiev divorced his wife—she thereby lost

her ‘protection’ and was at once arrested on a trumped up charge and

sent to a prison camp.

When the West first heard Prokofiev’s great Romeo

and Juliet music, his setting himself upon the pedestal with Tchaikovsky,

they were puzzled by the music, called it "satirical." Prokofiev

had been concerned about the final scene, and considered for a while

changing to a happy ending. "Dead people can’t dance," he

said. His solution to the problem, having Romeo dance with Juliet’s

presumed dead body proved achingly effective, as did the brilliant use

of the military snare drum in the music to symbolise the inexorable

working of fate. Romeo and Juliet is, after all, an anti-war

statement. Soviet productions tended to suggest that Juliet’s family

were the evil wealthy capitalists and Romeo’s family the common people,

injecting some Marxist class struggle into the plot; but this was easily

removed from most Western productions. Today the music does not bewilder,

and we luxuriate in its beauty and power. Those who have never seen

the ballet probably cannot imagine how a Shakespeare play could be translated

to a wordless medium, but here it is; almost every detail of the story

is expressed with great colour and intensity.

The all time great video performance of this work is

the Soviet film from 1954 with the Bolshoi Ballet, with choreography

by Leonid Lavrovsky, Gennadi Rozhdestvensky conducting, and with Galina

Ulanova and Yuri Zhdanov in the title roles. Faded colour and wavery

sound notwithstanding, one must have this version! It is one

of the greatest films of all time, and certainly the very greatest ballet

film. Every frame looks like a Renaissance painting. The impact of this

film is shattering; I could only bear to watch half of it in a day.

This choreography makes almost exclusive use of the motions of classical

ballet. The outdoor scenes were actually filmed out of doors on an enormously

spacious village set in the sunlight with real mountains and clouds

in the background, or at night with the wind blowing the funeral torches

into knives of light. The Maazel recording on Decca of the complete

score runs to 140 minutes. All ballet versions are cut to some degree;

here a number of dances had to be cut to bring the running time down

to 91 minutes, but all the familiar tunes seem to be there. This version

is available on video tape and laserdisc from collector sources—try

searching the ‘net under "Ulanova Juliet." Buy what

is available now and hope we will some day soon have a completely restored

version with newly recorded sound.

Another available La Scala version is from 1982 with

Rudolf Nureyev as choreographer and dancing the role of Romeo. At 129

minutes’ length, it nevertheless cuts some familiar music, replacing

it with repetitions of other music. This is deceptively advertised as

"Nureyev-Fonteyn" but in fact Dame Margot Fonteyn here plays

only the bit part of Juliet’s mother, a pantomime role, and Juliet is

played by Carla Fracci. Nureyev’s choreography not surprisingly expands

the part of Romeo and gives him many opportunities to perform his famous

leaps. There are many fine moments in this version—the stage lighting,

the costumes, some of the bits of ‘business.’ I especially liked the

first big fight scene where the dancers, the men aggressively egged

on by the women, start out with their fists and only later use their

swords. But the choreography naively misses not a single opportunity

for a grand gesture or a set piece by the corps de ballet, so that by

the end there is nothing left but some tiresome and bathetic pantomime.

The picture and sound are adequate but undistinguished. If you collect

versions of this ballet you will want this one, too, but not as the

only version in your collection.

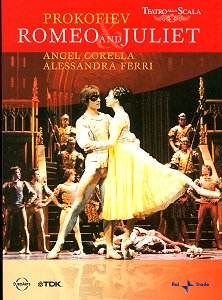

This La Scala 2000 performance is with choreography

utterly unlike any of the other versions. Picture and sound are excellent.

The orchestra plays extremely well, having only a little trouble early

on with some of the polyrhythmic passages; they lack only that tiniest

bit of sharp rhythmic edge other renowned orchestras have brought to

this music. The colours are soft. One wishes that the lighting contrast

had been more varied between those scenes which occur out of doors or

at night as compared to those occurring indoors. I confess to being

a little put off by the spectacle of a crowd of identical young men

in glistening tights and swelling baskets prancing around the stage—red

for Capulets, green for Montagues, virtually naked from the sternum

down except for the merest film of iridescent Spandex. In the Ulanova/Zhdanov

film every fighter had his own unique, violent persona with authentically

rugged costumes that did not hinder the motions of the dance. At La

Scala 2000 the fight scenes are vigorous, but not savage; they were

notably more violent in La Scala 1982. This is, after all, a parable

in protest against war and the horror of violence is part of the message.

The acting is exceptionally vivid, especially Ms. Ferri

as Juliet whose body language conveys every thought from moment to moment.

She doesn’t need to speak for you to know what’s she’s thinking and

saying, and Corella is in every way her worthy partner. In this version

Romeo and Juliet die unblessed by Friar Lawrence. The familial elders

do not rapproche on stage, denying us even that mere hint of

a happy ending.

For La Scala to have mounted at least two strong productions

of this story may have to do with a little more than just the quality

of the music. The story not only takes place in Italy, but was originally

an Italian story. Prokofiev’s source was Shakespeare, Shakespeare’s

source was Arthur Brooke, and Brooke’s source was Mateo Bandello whose

work derives from numerous Italian plays, and them perhaps ultimately

from the ancient Greek tragedy of Pyramus and Thisbe. But several of

the familiar characters we know are Shakespeare’s alone.

Regrettably I was unable to obtain in reasonable time

a DVD copy of the widely acclaimed 1966 Royal Ballet performance with

Nureyev as Romeo and Fonteyn as Juliet, choreography by Kenneth MacMillan,

and with John Lanchberry conducting the Orchestra of the Royal Opera

House, running 125 minutes. Reviewers overall praised the chemistry

between the star dancers, many commented that although Fonteyn did not

look 14 years old, she nevertheless danced flawlessly. Neither picture

quality nor sound quality were found outstanding even by 1966 standards.

Apparently the PAL versions are better than the NTSC. Some found fault

with the video direction. I was also unable to obtain the 1992 DVD version

by Ken Nagano and the Lyon Opera Ballet with choreography by Angelin

Preljocaj and starring Pascale Doye as Juliet and Nicholas Dufloux as

Romeo. This production is sharply revisionist, set in the severe environment

of a Communist dictatorship and using about half of the score padded

out with repeats to fill an 85 minute production. Some critics enjoyed

it, but all agreed it is not to be recommended to persons seeking the

classical ballet scenario.

Well, what is my advice? If you must have the best

and are not put off by dated video and sound quality, you want the Ulanova/Zhdanov

version and/or the Nureyev/Fonteyn 1966. If you don’t know much about

ballet and want a good show overall, your choice is Ulanova/Zhdanov.

If you must have the finest sound and picture quality available in a

classic version, your only choice is Ferri/Corella. If you want the

prettiest Juliet and the handsomest Romeo surrounded by beautiful bodies

in a classic version, again, your choice is Ferri/Corella. For the best

costume and set design the nod might go to Nureyev/Fracci at La Scala

1982, with Ulanova/Zhdanov a very close runner up. If you want to explore

the unusual, include Nagano’s Doye/Dufloux version. If you dearly love

the music and the ballet and have the space and money, there are significant

virtues in all these performances and you will want them all.

Paul Shoemaker