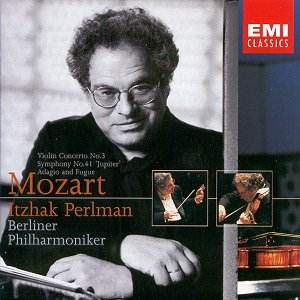

Perlman’s particular blend of virtuosity, big-boned,

muscular tone quality and musical intelligence have given much pleasure

over the years. It is pretty obvious from the packaging here that EMI

are making him (rather than Mozart) the reason for buying yet another

‘Jupiter’ and G major Concerto, so the question has to be – is

it really worth a full price outlay? I’m afraid, despite good things

along the way, that the answer is a very firm ‘no’.

The reasons are apparent from the start of the concerto,

which is the most recorded of the five. The opening allegro resolutely

refuses to take wing, with a stodgy basic tempo and smoothed-out phrasing

keeping things earthbound. A comparison with my current favourite among

modern instrument performances, a DG disc featuring the Camerata Academica

Salzburg under Augustin Dumay, who is also the soloist, serves to reinforce

the shortcomings in Perlman’s version. Dumay adopts a marginally brisker

pulse but, more importantly, he makes sure that there is dynamic contrast

between forte and piano, gives weight to accents and finds

an inner rhythmic life almost wholly missing on the EMI. The slow movement’s

operatic feel is nicely played up by Perlman, who finds the ‘long line’

in the phrasing, but even here there is precious little charm or elegance.

The pared down Berlin Philharmonic play well enough, though there is

little point in nodding to period practice by reducing forces and then

giving the most flat-footed of romantic readings. The rondo finale is

not much better, with wind detail blurred and accents again rather under-played;

Dumay’s Salzburg forces find just the right balance, and the sheer enthusiasm

and buoyancy is thoroughly infectious, as indeed it should be.

The great ‘Jupiter’ Symphony suffers many of

the same traits. There is certainly an epic quality that places the

work, correctly, as one of the greatest of pre-Beethoven symphonic statements.

The problem lies once more in a refusal to play up the inherent contrasts

in the music. It is one thing to share a long, epic journey but there

is little sense of the piece having the sort of ‘restless grandeur’

that Andrew Huth’s liner note mentions. The record catalogue boasts

a plethora of worthy contenders, my own current frontrunner being Charles

Mackerras and the Prague Chamber Orchestra (Telarc), a performance brimming

with life, colour and imagination. Yes, Mackerras is a little unyielding,

even aggressive in places, but he makes you sit up and take notice.

The miracle of counterpoint that is the finale should surely sweep you

along with its energy and momentum. In Perlman’s hands there is a flicker

of excitement here and there, but the basic feeling is one of being

underwhelmed, and I had to agree with the BBC Music Magazine, who found

the whole performance ‘heavy and featureless’.

The short, dark Adagio and Fugue in C minor

suits Perlman’s approach best on the disc, with Berlin brass resplendent

and the stately, funereal tempo apt, but this is hardly enough to sway

matters. The recording quality is good, and fans of the artist may well

want to investigate this release, but for anyone who cares about Mozart,

this is something of a non-starter, particularly given the wealth of

competition, much of it at medium or budget price.

Tony Haywood