Wilhelm Middelschulte was one of the two men Ferruccio

Busoni referred to as ‘the Gothics of Chicago’ (the other was the contrapuntal

theorist Bernhard Ziehn). After passing almost a century in near-complete

obscurity, Middelschulte appears at last to be emerging into the light.

In 2000 cpo released a CD of his organ music – the Toccata on ‘Ein'

fest Burg’, Contrapuntal Symphony, Two Studies on the

Chorale ‘Vater unser im Himmelreich’, Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue,

Perpetuum mobile and Chaconne – played by Jürgen Sonnentheil

(cpo 999 739-2). On 18 February 2003 the ever-venturesome Jane Parker-Smith

included his transcription of the Chaconne from the D minor Partita

(Bach-Busoni-Middelschulte: the list of names is growing) and his own

D minor Passacaglia in her concert in the Royal Festival Hall series

of organ recitals. Parker-Smith, indeed, is a Middelschulte enthusiast,

with his entire output in her collection. Perhaps his time is coming.

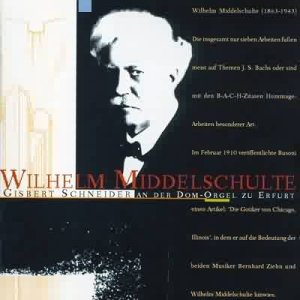

Sonnentheil was beaten to the draw, in fact, by Gisbert

Schneider, whose CD of Middelschulte organ music appeared from the German

label Cybele in 1999, although it is only now that it has come to my

attention. It is, in all fairness a magnificent CD, presenting magnificent

music. Middelschulte was a natural contrapuntal thinker, and his writing

suits the organ perfectly. The pieces presented here show him thinking

on a large scale, too: the Passacaglia, dark and severe, clocks in at

almost fourteen minutes, while the five-movement Concerto on a Theme

by Johann Sebastian Bach takes 35, and the Canonic Fantasy and

Fugue accounts for 25. The Concerto is a stunning demonstration

of Middelschulte’s musical imagination: the theme is that of the fugue

from the E minor Prelude and Fugue, BWV548, a chromatic wedge shape

which obviously cried out to Middelschulte with its latent developmental

possibilities. But the work is no Bachian imitation: Middelschulte writes

his own music, in rigorous and exciting counterpoint – it’s the organ

equivalent, if you like, of Busoni’s Fantasia contrappuntistica,

and one hears immediately why Middelschulte commanded Busoni’s respect.

The Concerto’s first movement contains a double fugue, the scherzo is

a canon at the octave, the Adagio a surprisingly brisk passacaglia,

the Intermezzo a fearsomely difficult pedal solo almost four minutes

in length, and the Finale a passacaglia with 39 variations, where I

don’t think he quite sustains the tension for all of its length, though

the music is never anything less than impressive. Likewise the Canonic

Fantasy and Fugue, where just now and again the onwards impetus

sometimes sags. What amazes here is Middelschulte’s contrapuntal virtuosity:

the Fantasy consists of no fewer than 43 canons on BACH, presented in

a bewildering variety of ways, and the fugue – presenting first the

BACH fugal subject from the nineteenth fugue of The Art of Fugue,

then the fugue theme from the D minor Toccata and Fugue, BWV565, the

‘Confiteor’ from the Mass in B minor, and finally the principal theme

of The Musical Offering – ends, God help me, by combining all

four! It’s a dazzling display of the contrapuntist’s art, and it’s thrilling

music, too, the closing bars blazing out in emphatic glory.

Gisbert Schneider gives heroic performances – this

must be appallingly difficult music to play, but there’s no hint of

strain in what he does; Parker-Smith perhaps played the Passacaglia

more sheerly excitingly, but it’s hardly fair to compare a recording

with a live performance. Friedhelm Onkelbach’s notes are helpful and

detailed, with six music examples to keep us au fait with what’s

going on in the music. The recorded sound I found a little distant on

first listening, but my ears soon adapted, and when the Erfurt Cathedral

organ is working on full power, it makes a magnificent noise.

Martin Anderson

![]() Gisbert Schneider (organ

of Erfurt Cathedral)

Gisbert Schneider (organ

of Erfurt Cathedral) ![]() CYBELE 050.201 [74.31]

CYBELE 050.201 [74.31]