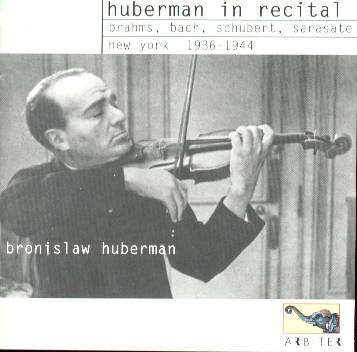

For so elite – if controversial – a musician Huberman’s

recordings are relatively sparse. Arbiter has therefore put us in their

debt by releasing a disc that expands his discography by including the

Brahms sonata in G – he’d famously played the Concerto as a boy in the

presence of the composer - and the Schubert Fantasie. And some idea

of his overwhelmingly involving Bach can be gauged from the Partita

in D minor which has survived albeit in less than perfect sound. We

should be grateful for the unsparing efforts of Seth Winner who worked

on the glass-based acetates, subsequently copied onto tape. The Bach

was made on a lacquer.

Huberman was one of the most individual of violinists

and one who still divides critical opinion. His Brahms (New York, April

1943) is an immensely generous performance but as ever critical debate

will turn to his tonal qualities. I find myself swept up by Huberman

even as I register doubt and objections. So for example his tone sounds

thin, and frequently very dry, the vibrato unwarmed, his portamenti

in the opening movement excessive and exaggerated in the interests of

maximal emotive impression. The dynamics are in a constant, vastly entertaining

and meaningful sense of flux – whether they are convincing is another

matter - and he does once or twice attack from under the note. There

are some minor technical problems but in the main his left hand is under

firm control. What will take a deal of getting used to (for those unfamiliar

with Huberman) is the problematical and anachronistically employed vibrato

usage – and the expressive whitening, a sudden bleaching, of tone in

which he engages. For all that this is decidedly not my idea of a forward

looking twentieth century violinist I cannot help but admit that the

latent power and seriousness of his conception has powerful attractions.

And his diminuendo on the last phrase of the first movement is striking

indeed. In the second movement he manages to etch deep meaning from

within the text – the means, tonal and otherwise by which he does so

are problematical but somewhat beside the point – as he develops an

unstoppable, almost oratorical grandeur. At moments like this one can

understand the near adulatory appeal of Huberman in central Europe (where

he was especially admired). There is a fusion of transcendence and philosophic

seriousness difficult to resist. It’s true that his tone remains unwarmed

and where vibrato is applied it is not uniform and continuous (though

Huberman was a near contemporary of Kreisler he never really absorbed

Kreisler’s modernising trends in that respect). Nevertheless Boris Roubakine

plays with witty charm and Huberman’s phrasal elasticity generates an

undeniable nobility and grandeur of expression. It should be noted that

there is a little damage on the acetates from about 5.20 onwards, some

pitch fluctuation as well but it’s temporary and has been limited.

The Bach Partita is an especially valuable survival,

dating from December 1942. He’d recorded the Concertos in A and in E

with the Vienna Philharmonic and Dobrowen on a single day in 1934 and

had recorded a few isolated movements from the Sonatas and Partitas

but this Partita (with the Chaconne) - although it’s made a commercial

appearance before - is intensely interesting. The sound is poorer than

the Brahms and there are some swishes but we can still hear a great

deal and listen through the impediments to the heart of Huberman’s performance.

His vibrato in the Courante is slow and very wide and especially employed

as a climactic expressive device, and at paragraphal or phrase endings

- rather like a monumental full stop. But there is wonderful clarity

of voicings and he opens the Sarabande in powerfully dramatic fashion,

taking the movement by the scruff of its neck; notes positively leap

from the grooves. As for the Chaconne it is once more a question of

greater architectural and emotive issues taking precedence over niceties

of bowing or vibrato usage. Those who think that, in William Primrose’s

words, Huberman "scratches abominably" will find ample documentary

evidence to support the charge. Those, equally, who revere his magnetic

drive, will use these performances as evidence for the defence, should

such be necessary.

In the extremely difficult Schubert Fantasie – a graveyard

for the unwary duo – his and Roubakine’s sagacity is fully developed.

Whilst I admired the contours of the performance and the exceptional

control exercised by both men there were times when I wasn’t able, fully,

to reconcile romantic impress with the dictates of the structure. The

on/off vibrato usage and the occasionally desiccated tone – this performance

dates from a concert in January 1944 – are not ultimately to the work’s

advantage. Sarasate’s Romanza Andaluza is a part of his accepted

commercial discography (he recorded it twice, in 1924 acoustically and

again in 1930, both times with Siegfried Schulze) and here the pianist

is unidentified (though it might be Schulze). It’s the earliest item

here by far, recorded in April 1936, but in good sound. This heats up

very nicely indeed and is on balance the best of the now extant recordings.

The endemically slow and wide vibrato is no hindrance here to some marvellous

theatricality and panache.

This is a release of striking importance to those interested

in the development of violin playing in the twentieth century. The good

notes are by Allan Evans who cites revealing comments made by Felix

Galimir; the transfers are surely of pretty optimum quality. Striking

then and exciting too, revealing an indelible talent whose live performances

take on renewed almost miraculous life here.

Jonathan Woolf