Is Ginastera as popular as he ought to be? He is reasonably

represented in the record catalogue (though his operas are noticeably

absent) but I can't help feeling that his music ought to be more popular

than it is. Perhaps he has the misfortune to be still regarded as a

Nationalist composer, at best a sort of Argentinian Bartók. His

music has gone through distinct phases, starting with works in a purely

nationalistic folk-idiom he gradually absorbed and sublimated the folk

material. Experimenting with serialism in the 1950s, his style developed

into something unique which, whilst still owing something to his Argentinian

roots, is worlds apart from kitsch folkloric extravaganzas.

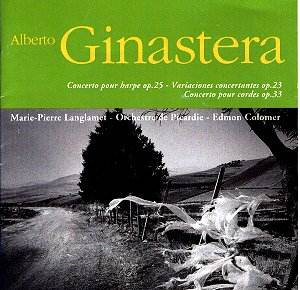

The Harp Concerto was written in 1956 but only

received its first performance in 1965 when Nicanor Zabaleta performed

it with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy. An attractive

work which flirts with dissonance whilst remaining attractively melodic,

it is well scored so that the harp is never overwhelmed by the orchestra.

In the first movement, highly rhythmic sections on the full orchestra

alternate with rather more rhapsodic episodes which allow the harp to

shine. It concludes with a surprisingly quiet finale. This leads in

to the rather Bartókian slow movement. The rather angular melodic

material, hauntingly played, creates an atmospheric movement. This leads,

via a surprisingly low key cadenza, into the finale which is driven

along by the underlying syncopated rhythms. The Orchestra de Picardie

respond very well to Ginastera's taut rhythms and harpist Marie-Pierre

Langlamet relishes the opportunities that Ginastera gives her. It is

not a bravura work, but the solo parts contains much that is subtle

and attractive.

In the Variaciones Concertantes, written

in 1953, we reach one of Ginastera's most well known and attractive

orchestral works. In the composer's own take on concerto grosso form,

a series of 12 variations on an original theme provide solo opportunities

for most of the section principals in the orchestra. The harp and cello

introduce the theme in a prelude suffused with warm Latin light, the

composer then carefully shapes the different variations so that the

resulting work has a satisfactory shape, concluding with a rousing rondo,

a sort of South American fiesta. All the principals play well and the

different variations show the orchestra off well, though there was the

odd moment of uncertain tuning. The most virtuoso variations are probably

the giocoso flute one and the clarinet scherzo, but the horns have a

striking pastorale moment and the trumpet and trombone a rather rhythmic

one.

The Concerto for Strings was written for Ormandy

and the Philadelphia Orchestra and was premiered in 1966. Ginastera's

style had developed, during the late 1950s and 1960s he had been writing

music in his own, distinctive brand of serialism. The composer himself

described the 'Concerto for Strings' as belonging to his neo-expressionist

period. Like the Variaciones Concertantes the concerto calls

for a solo quintet (2 violins, viola, cello and double-bass) to contrast

with the main body of the strings. This is tougher music than the other

two pieces on this disc. And lacking woodwind and brass, it does not

have the attractive gloss which Ginastera's brilliant orchestration

gives. But it is a strong piece and given a fine performance here. It

begins with a series of variations for each of the members of the solo

quintet. The cadenza-like theme is stated first by the first violin

and incorporates quarter tones. The second movement is the suitably

titled Scherzo Fantastico. The slow movement is a beautifully anguished

Adagio which leads to a hard-driven, fast and furious finale. This is

strong music and at times the strings of the Orchestre de Picardie seemed

a little stretched, but they give a tremendous performance and their

lean tone suits this masterly work. I Musici di Montreal on Chandos

have the benefit of a somewhat clearer recording and give a technically

brilliant performance. But their disc is devoted simply to string music

from a variety of composers, rather than the current discís rather illuminating

survey of Ginasteraís music.

The Orchestre de Picardie is composed of 35 musicians

and gives around two dozen concert a year both in Picardie and in the

larger towns in France. Their musical director, Edmon Colomer, is a

Spaniard. He seems entirely in sympathy with Ginastera's music and the

orchestra respond well to his direction. You could imagine performances

given with lusher string tone perhaps, but I rather think that the Orchestre

de Picardie's lean tone serve this music well. They have also recorded

discs of music by Honegger and Milhaud, so it is enterprising of them

to commit a whole disc to the South American, Ginastera.

You can gain some insight into the reasons for the

critical reaction to Ginastera in Europe when you consider the sort

of music being produced by the European avant-garde at this time. No

matter how much he experimented with serialism, Ginastera's brand of

well crafted, approachable music must have seem enormously old fashioned.

But in today's rather more forgiving, pluralistic society there is no

reason why this attractive music should not get the success it deserves.

Robert Hugill