Leginska’s name has always been more honoured in the

breach. A notable propagandist for women musicians – she was a composer

and a conductor as well as a pianist – her reputation suffered inevitable

decline, one exacerbated by the relative paucity of her recordings.

The fact is that she had a most distinguished pedigree; a Leschetizky

pupil until she was sixteen, studies in Berlin, a performance of the

Henselt Concerto with Henry Wood whilst still in her mid-teens. Following

her (failed) marriage she went to America where she continued to study

– theory with Rubin Goldmark and composition with Ernest Bloch (three

operas of hers, Gale, The Rose and the Ring and Joan

of Arc, were written in the 1930s – she seems also to have excelled

at orchestral works). Like Iturbi shortly after her, conducting became

a passion and at thirty-seven she studied its technicalities with Robert

Heger and Eugene Goossens (an old friend) and in time became known as

one of the first major women conductors with a string of prestigious

engagements. She conducted – opera as well as orchestral concerts –

in London, Salzburg, New York and Boston. In 1932-33 she was conductor

of the Montreal Opera Company.

Leginska was born Ethel Liggins in Hull in 1886. It

was the snobbish Lady Maud Warrender who suggested the Slavic name to

enhance her career though she was hardly unique in feeling that an English

name was a hindrance to wider acceptability, not least in her own country.

She was one of the most interesting and picaresque of British pianists

born between Harold Bauer (b.1873) and Myra Hess (b.1890) – though one

arguably less talented than her now little known contemporary, the superb

Winifred Christie (b.1882). Like Bauer and Hess she gravitated fairly

early to America (Hess was appreciated early in America; her iconic

status in British musical life was not as secure as it now retrospectively

seems always to have been). This is apparently the first time that her

American Columbias, recorded in New York, have been reissued en bloc

and they disclose a musician of distinct and considerable - though not

unproblematic – gifts; sensitive, tonally splendid, with a command of

phraseology that is frequently compelling.

Schubert, Chopin, Rachmaninov and Liszt are the four

composers represented on these early electrics. The Four Impromptus

date from 1928 and were issued as Set No. 93. The B flat major embodies

a genuine nobility – albeit in a rather deadpan sort of way – but the

concluding F minor (No. 4 – Allegro scherzando) generates its

own internal momentum and is full of contrast, both colouristic and

in terms of depth of sound. The Six Moments Musicaux, together with

the Impromptus, represent her primary contribution to the discography

but are uneven. The first is full of fluency and tonal sagacity with

strong architectural wisdom but the second, in A flat major, is rather

earthbound with hints of metricality. The little F minor makes little

impression in her performance but the C sharp minor is a fine reading

– sonority, span and phrasing held in excellent equilibrium and no sign

of any sectionality in a piece that can tend to buckle in less perspicacious

hands. She is quite emphatic in the F minor (No. 5) and cultivates a

rather rugged view of the concluding Allegretto though not one without

interest. I was less taken by the Schubert-Tausig; rather finicky phrasing

to my ears – italicised and stolid. I admired the way she abjured the

speciously virtuosic, the overemphatic blunderbuss approach and the

contrast she cultivates between rigidity and the flowing central panel

of the music but I think it comes at too much of an overall cost.

Her Chopin is only so-so. The Prelude in D flat major

in particular fails to convince because of insufficient engagement and

poor tempo relationships. The Rachmaninov lacks fire; she seems to value

architecture at the expense of leonine drama (which is not the same

as vulgarity) so there’s a lack of dramatic etching in the G minor Prelude

and whilst her technique seems quite adequate for this and the C sharp

minor, no sparks fly. The Liszt is not unattractive, there’s some beautiful

treble-orientated sonority but again she hardly comes across as a romantic

virtuoso of declamatory vision.

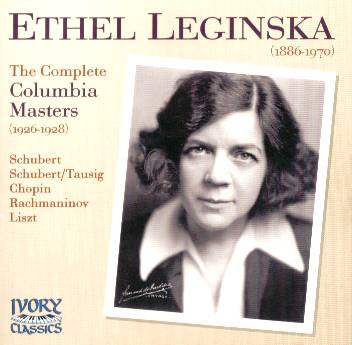

Notwithstanding these critical observations this is

a genuinely useful release. It restores important recordings to the

catalogue and does so moreover in a helpful and attractive way. The

transfers have been expertly handled and the booklet is both handsome

and full of pertinent biographical information; period photographs only

serve to enhance the attractiveness of the design – something of a model

booklet. Bonus points to the imaginative mind that thought to reproduce

the Columbia 78 label of one of the Moments Musicaux as part of the

jewel case. A class act.

Jonathan Woolf