This is a doubly felicitous release as it gives us

concerto performances recorded privately in the 1960s and also enlarges

Morini’s discography. She recorded the Bruch G minor with the Berlin

Radio Symphony and Fricsay but neither the Spohr nor the Wieniawski

were otherwise commercially recorded. A Sevcik student at the age of

seven, Trieste-born Morini made her debut with Nikisch at the age of

twelve and was soon taking prestigious engagements as well as embarking

on a series of recordings for Grammophon and Polydor in the 1920s. Despite

early success in America in 1930 – and renewed ones following her enforced

emigration a few years later - her career slowly petered out. The unpleasant

details of the theft of her Stradivarius and all personal papers shortly

after her death aged ninety-one in 1995 make for grim reading.

These performances with Frederic Waldman and his Musica

Aeterna Orchestra were recorded privately on acetate by a pupil of the

conductor’s. Though Morini was tagged the Word’s Greatest Woman Violinist

– a publicist’s puff if ever there was one and a self-limiting one to

boot – she was indeed an unusually refined and elegant player. She had

a small tone, lyrically deployed, with a strong albeit not invincible

(but still remarkable) technique, reliable intonation but without a

distinctive tonalist’s colouration. This could work to her advantage

in baroque and classical works but was sometimes less than ideal in

broader more obviously romanticised canvases (though she was admired

in Brahms and Tchaikovsky).

The acoustic is quite dry but acceptably so and the

acetates have come up fresh and full of detail. One immediately notices

in the first of the performances, that of the Spohr (recorded in 1963

and the earliest of the trio), that Morini’s vibrato is extremely sparing.

She makes one particularly gauche slide in the opening Allegro but otherwise

her portamenti are as sparing as her vibrato is controlled though there

are no lack of finger position changes and other intensifying devices

to wring colour and spice from the score. Problems reside in her lower

two strings which by this time – she was 62 – sound rather dry and unwarmed

and her lack of charismatic power at climaxes and before orchestral

tutti. The upper strings sound - in Morini’s terms – fine, sweet and

tight but the disparity between them and the consequent unequalized

scale is quite noticeable. The result is rather a case of two distinct

voices; tight and sweet upper and far more slow and dull sounding lower.

There is a compensatory amount of sheer elegance in the slow movement

and some elfin playing as well – mobility and technical address - and

in the finale her dancing confidence is spiced with delicious humour.

The Bruch (from 1966) opens chastely, without theatrical flourish (but

with a momentarily distracting pre-echo). Morini avoids the oratorical

and deigns to dig into the string; she’s not for making a big sound,

preferring instead clarity of passagework and forward-looking drive

without specious drama. She controls the line of the Adagio with affectionate

generosity but again the vibrato usage is idiosyncratic and in some

ways pre-Kreislerian in its abjuring of constant application. In the

finale, attractively played and phrased though it is, the lack of tonal

opulence may come as a burden for those used to more passionate and

powerful players.

The Wieniawski features a nice flautist who sparkles

in the Allegro moderato opening movement (and distracts one perhaps

from Morini’s temporary flatness). Her playing should in toto

be seen as independent of the prevailing orthodoxy or orthodoxies of

then contemporary violin playing. This is a work that one associates

most strongly with Elman, Heifetz and Stern and their individual sonorities

could not be more distinct from Morini’s way with the work. Some of

her passagework sounds scratchy (maybe not helped by the recording)

and tonally somewhat unlovely but there are piquant slides and a general

stylishness that can communicate something of her obvious appeal. Waldman

is a robust collaborator and he points the slow movement to good effect

allowing her to shape the line with affection. There is occasional lack

of colour in her playing – as in the finale – and the coolish temperament

is not what might look for in a work like this but there’s little doubting

her fine style and sense of momentum.

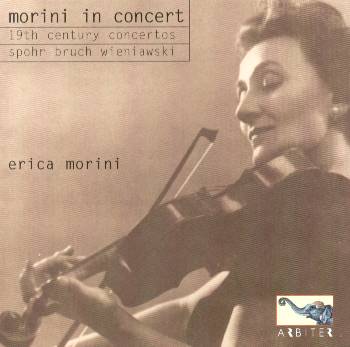

This is one of a number of Morini discs that Arbiter

have in their catalogue. With Allan Evans’s useful notes and some nice

accompanying details – programmes, photographs – this is a tempting

prospect. Those who want to acquaint themselves further with Erica Morini’s

very individual talent will find much to occupy them here.

Jonathan Woolf