If all the music by the British-based composer, pianist,

teacher, publisher and piano manufacturer Muzio Clementi were as rewarding

as the lyrically spontaneous Molto adagio, sostenuto, e cantabile

of op. 40/1 or the first movement of op. 40/2 with its strong introduction

and splendidly driving Allegro con fuoco, it would probably be

under our fingers and in our concert halls with as much frequency as

late Haydn. On the other hand, if it were all as dry as the wretched

canons that make up the third movement of op. 40/1 we should scarcely

find time for him at all.

Most honoured in the schoolroom, where his six Sonatinas

remain the standard gateway to the classics – and rightly so, for their

lively invention and formal clarity put them on a higher level than

most similar works – Clementi was plainly far more important than the

struggling student realises. Much admired by Beethoven (less so by Mozart),

his long series of sonatas has always intrigued musicologists for its

anticipation, in the earlier works, of certain aspects of the Beethovenian

style, and for the proto-romanticism of a number of passages in the

later pieces. Indeed, the exact relationship between Beethoven and Clementi

is not always easy to establish. The first movement of op. 40/3, for

example, after an imposing introduction, leads into a D major theme

so identical in its pianistic texture (but not notes) to the opening

of Beethoven’s op. 28, also in D major, that one can only gasp at such

a blatant "crib". Clementi published this sonata in 1802,

the Beethoven had been published in 1801, so Clementi could have

seen the Beethoven, grabbed his pen and pinched the idea in time for

his own sonata, but do we actually know when Clementi wrote this

work? The booklet notes, while noting the similarity, do not offer a

date for composition. We know for sure that Clementi’s previous sonata

publication was in 1798, allowing the logical assumption that op. 40

was composed gradually in the intervening three years. Furthermore,

as early as 1799 the publication of four new sonatas by Clementi had

been announced. They were not issued, but what could they have been

if not those of op. 40, maybe withheld for revision? The "crib",

then, may in reality be a remarkable coincidence.

A fascinating if frustrating composer, no one has ever

accused Clementi of excessive brevity. Just six sonatas on two well-filled

discs suggests in itself something closer to Schubertian heavenly lengths

than Beethovenian concentration, and the undoubted inspiration of the

celebrated "Didone abbandonata" sonata is weakened by its

sprawling structure. Pianists often turn to these sonatas in their own

music studios, but less often feel impelled to play them in public.

In many ways the greatest satisfaction is to be found in Clementi’s

earlier and more disciplined sonatas; however, this album gives us some

of his last works, op. 40, published in 1802 as already said, and op.

50 which though published in 1821 is thought to have been written around

1805.

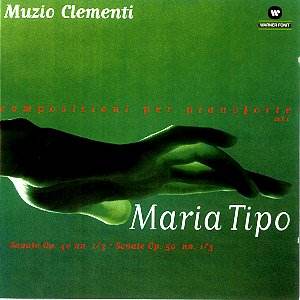

Maria Tipo has been a widely respected name in Italy

over the last few decades and plays with clarity and musicality. She

is capable of great vitality and also shows much poetic sensibility.

If I am not altogether convinced, this regards a problem which only

an expert in Clementi editions can resolve. I shall start by declaring

that I have before me the Henle Edition, edited by Sonja Gerlach and

Alan Tyson, of op. 40/1-2 and op. 50/1. Over the last 50 years Henle

have established a reputation for the rigour and scholarship of their

Urtext editions and Alan Tyson is one of the leading experts in Clementi.

The correctness of this text is presumably beyond doubt. The trouble

is that it was not available to Maria Tipo since it was published in

1982. I also have, for these same three sonatas plus op. 40/3 and op.

50/3, a French edition published by Heugel in 1924. This has numerous

divergences as regards dynamics and phrasing though they seem to agree

over the actual notes. Whether these divergences derive from variant

readings of Clementi’s own text or from the "creative" editing

considered acceptable in those days I have no way of knowing. In any

case, what Maria Tipo plays is often different again. Maybe she is "doing

her own thing" but I have never supposed her to be that sort of

pianist and I suspect she is scrupulously following some Italian edition

current at the time of the recording.

To take one example, from b. 99 of the first movement

the Henle Edition (you can follow this up on disc 1 between 4’ 56"

and 5’ 18" of track 1) marks a steep crescendo leading to forte

and then fortissimo at b. 103. The music then storms forward

till the dramatic pause at b. 109. The Heugel edition is identical save

for a the omission of a few extra sforzandos. But Tipo

makes a longer, more gradual crescendo and then tapers away to reach

piano before the pause, which is therefore not dramatic at all.

Surely the effect would be much stronger as written in Henle and Heugel?

Then the slow movement which follows has, in Henle,

numerous accents, sforzandos and hairpin crescendos and

diminuendos which, if observed, would create an altogether more

intense effect than the gently poetic rendering we have from Maria Tipo,

who frequently reverses the indications entirely. In this case the Heugel

edition contains precious few of these expression marks. Now if Clementi

had really left the music as bare of expression marks as the Heugel

edition (and maybe that followed by Tipo) lets us suppose, then Tipo’s

solutions would be perfectly acceptable. But I cannot believe that Alan

Tyson added all these things without just authority, and the nature

of the music is thereby changed.

However, while Maria Tipo may be the victim of a poor

edition, and cannot be blamed for this since the Henle was not available

to her, at the same time her general approach (maybe under the influence

of this edition) does seem inclined towards lessening the stronger qualities

of the music. While I accept that to storm about in Clementi as if he

were Beethoven can be counter-productive, I find her too willing to

stem the flow and drift into a poetic revery of her own. Take the opening

of op. 50/1. After just four bars of strong music there comes a passage

marked dolce and con espressione. Tipo is certainly that,

but does she have to lose all sense of direction so early in the movement?

Certainly, Clementi must take his share of the blame, but a more forward-moving

performance might have shown him in better light. The suspicion arises,

as the discs procede their agreeable way, that one is listening to a

vast collection of cadenzas.

You will gather that I am rather perplexed as to whether

this is the best presentation of some often very fine music. The booklet

contains two excellent essays, but you’ll be better off if you can read

them in the original Italian, thereby avoiding such quaint phrases as

the following: "The second movement, ‘Molto Adagio, sostenuto e

cantabile’ has a very sweet beginning but then crumbles into a perhaps

excessive proliferation of flowering that shadow the ‘cantabile’ qualities".

"Of the three Sonatas the first is perhaps the less interesting,

if not in the wide ‘Allegro maestoso e con sentimento’, so rich in figure

inventions and characterized by an orchestra like sounding pianism".

Christopher Howell