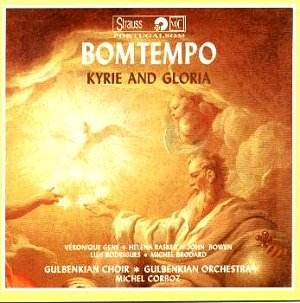

Bomtempo had risen to the position of first oboist

in the band at the Portuguese Royal Court but following political unrest

left first for Paris and later for London. It was in the French capital,

in 1818, that he wrote the Kyrie and Gloria and he subsequently

revised it in Lisbon in 1821 for its first performance, after his return

from self-imposed exile. I know Bomtempo mainly through his piano works

and it has been enjoyable to listen to the Kyrie and Gloria, works that

may not be formally or musically over-ambitious but which, within their

compass, still manage to be lyrical and are full of some refined orchestral

pointing.

The Kyrie is a reflective, somewhat tense work with

an ascending and descending bass line, aspirant and which builds in

volume and fervour. Though essentially homophonic there is plenty to

stimulate both vocally and instrumentally. The Gloria opens with a strongly

punctuated drive, the soloists making their presence felt, with plenty

of expressive choral moulding, supported by apposite diminuendi. The

string pointing in the Laudamus Te is reminiscent of Haydn in its elegance

and a fine duet between soprano Véronique Gens and tenor John

Bowen is supported by strong choral "pillars", well crafted

and dramatically cogent. Bowen is fine but Gens is the standout here.

In the succeeding Domine Deus Luís Rodrigues and Michel Brodard

are accompanied by strings, bassoon and trumpets; itís the close of

the movement in which resides the greatest surprise Ė a choral section

of beguiling plangency. Qui tollis is a trio for soprano, contralto

and bass. Italianate and long Ė in this performance itís over sixteen-minutes

it doesnít in truth possess quite the level of thematic material to

sustain that breadth but there are charming things here. The piping

clarinet for example makes an important appearance, At 3.50 the soloists

sing over a clarinet and pizzicato basses; the clarinet adds warmth

and the movement here becomes suffused in Italianate lyricism. Mezzo

Helena Rasker has a well-modulated depth and more importantly focuses

and blends her tone with Gens and Brodard. The strong edit as the movement

ends is probably due to audience noise and is reflective, I guess, of

the fact that this is a live performance recorded in the auditorium

of the Gulbenkian Foundation (the following day was presumably a repeat

performance or was used for patching, the notes arenít clear on the

point). Qui sedes generates a fine sense of momentum, a lively curve

of melody, one that becomes increasingly fervent with sure choral contributions.

The Cum Sancto Spiritu is performed with only one of its sections so

whilst itís an affirmatory way in which to end itís also very short

at 1.51.

So a successful work and performance, the first of

modern times. The experienced Michel Corboz directs with real sensitivity

not least in the important matter of the orchestral part, which because

it generally abjures monumental tuttis, relies instead on colouristic

inflection for maximum effect. Thus chamber sonorities predominate as

well as concertante sections. The choruses are involved and active ingredients

of Bomtempoís pattern and the Gulbenkian choir acquit themselves well.

Itís not a masterpiece and its Haydnesque character is very evident

but thatís no reason at all not to investigate a charmingly assured

work such as this.

Jonathan Woolf