Early music in the mid-1990s was obsessed with Venice.

With all the reconstructions of great moments in the history of that

favoured republic, ranging from Eliot Gardner's Monteverdi Vespers

recorded in St Mark's Basilica, through Paul McCreesh's Venetian

Coronation and Robert King's Lo Sposalizio Ascension Day

Ceremony recreation, to McCreesh's Music for San Rocco recorded

beneath the great Tintoretto canvases of the Scuola Grande of

the same name, it certainly appears as if Venice was the last word in

grand ceremonial. But it wasn't. Around the same period of the High

Baroque in the mid-17th century the sovereign Archbishopric of Salzburg

was a centre of counter-reformation majesty, helped by the completion

of the great cathedral in time for the celebrations of the 1100th anniversary

of the founding of the See. For that occasion Heinrich Biber, Salzburg’s

greatest musical luminary before Mozart, composed his vast 53 part Missa

Salisburgensis. Paul McCreesh and his Gabrieli Consort recorded

it for Archiv in Romsey Abbey, but Ton Koopman was able to go one better

for Erato with a live recording in Salzburg Cathedral itself. This new

Alia Vox recording of the 15 part Requeim follows in that mould, and

if recording Venetian music in St Mark’s was sumptuous, recording Salisburgensian

music in the enormous spaces of the baroque triumph that is Salzburg

Cathedral is something else altogether.

The 15 part Requiem was most likely composed for the

funeral of the man who was probably the greatest ruler Salzburg ever

had, Prince-Archbishop Maximilian Gandolph, Biber’s patron and a great

promoter of the arts in general, who died suddenly on 3 May, 1687. He

lay in state for six days, before being carried in procession to his

cathedral where this solemn Requiem was performed, having been composed

and rehearsed in the intervening six days. Biber must be considered

the major musical figure between Monteverdi and Bach and the more of

his sacred works that become available on recordings the more this view

will be confirmed. The Requiem à 15 may have been composed quickly,

but it shows no signs of it at all. It is unusual in several ways, not

least the key of A major (Biber’s other later Requiem is in the more

sombre key of F minor) and the inclusion of two festive trumpets and

timpani. While Biber considers aspects of death at various times in

this work the overall feeling is not one of sombre mourning but, possibly

befitting a great and genuinely much-loved ruler, of calm grandeur and

the confident assurance of victory and heavenly glory.

Biber understood these things, and so too does Jordi

Savall. This writer has long been a fan of Savall and his various groups,

but still he never ceases to amaze. There is something of a Midas Touch

in the man’s work. Maybe he just surrounds himself with the best musicians

to be had and lets them do their thing, but considering that this Requiem

was recorded live it is a remarkable performance. Certainly one would

expect excitement and drama from a live performance, but to get all

that together with a perfection of intonation and pacing, and a polish

and blend in both the instrumental and vocal ensembles almost defies

belief. The thing that is most exciting here is the tangible atmosphere

of the great space inside Salzburg Cathedral. The Mass opens with a

Marcia Funebre for trumpets and drums, representing the procession

arriving in the Cathedral. This opens with slow drum beats ringing around

the huge acoustic in a most unsettling way. The spaces really are vast

and the resonance can be nothing but a nightmare for the recording engineers.

What is even more remarkable is that the photos in the very glossy packaging

clearly show that the performers were distributed in front of the high

altar and in the four organ lofts that surround the crossing. These

are a good twenty feet up, and separated by huge spaces. Contemporary

engravings show us that this was how major musical events were performed.

How any sense of ensemble is possible one cannot imagine, but Savall

manages. The whole work proceeds in this stately manner without any

flagging or diminution of the beauty. It is a remarkable achievement.

The disc opens with the more well-known 10 part Battalia

for strings. This work uses several devices that are still considered

‘modern’ in our times - hitting the strings with the wood of the bow;

paper under the strings of the basses to imitate a snare drum, and,

perhaps most shocking of all, the simultaneous rendering of eight folk

songs in different keys and time signatures to illustrate drunken soldiers.

It sounds avant garde now; how it appeared in 1673 we can only

imagine. This is a 2002 recording, not made live, but in a generous

acoustic nonetheless. The playing is as sprightly and polished as one

would expect and the ensemble is suitable tight and vigorous. It is

somewhat surprising that the overall effect is not as exciting as one

would imagine it would be, given the interpreters. It is certainly extremely

listenable, but the presto is not breakneck speed, and the snap

pizzicato doesn’t feel so tangibly dangerous. Maybe one ends up expecting

too much of every Savall performance, but this is one work where the

extremes he does so well really do seem to be there for the exploring.

The feeling is just a little tame.

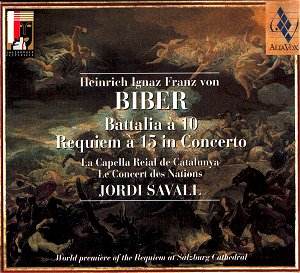

Even if the Battalia were not there at all and the

disc was only 44’ long it would be worth every penny for the Requiem

alone. Presentation is of the usual Alia Vox high standard. There is

an informative booklet essay - a little too heavily weighted towards

the much shorter Battalia than seems really necessary - and a good selection

of colour photos, all in attractive design. But how one would have loved

to be there at the concert! The recording is the next best thing.

Peter Wells