Isaac Stern once had a poor rehearsal of the Beethoven

Concerto with the RPO conducted by Beecham. Going to apologise the conductor

patted him aside and said things would be better in the following morningís

rehearsal. Come the morning and the violinist was handed a meticulously

marked score. Beecham had been up into the small hours noting points

to the librarian to mark. Stern played the rehearsal magnificently and

remembered the incident for the rest of his life Ė one of the highlights

he said of his career. Which might seem odd, when one considers Beechamís

reputation for slovenly indifference and the sometimes-fashionable opinion

of him as incapable of handling symphonic super-structures.

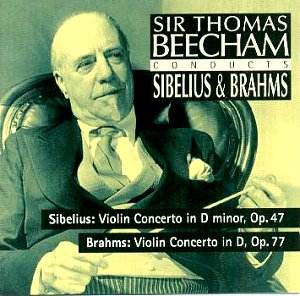

No sign of that here. In the case of the Sibelius he

was, Stokowskiís then-unissued slightly earlier recording notwithstanding,

a discographic pioneer. His recording with Heifetz, a scintillating

collaboration and easily the greatest of their not untroubled recordings,

remains devastating to this day. This later 1951 traversal with a very

different violinist is on a lower level of engagement. Though he was

to re-record it in 1969 with Ormandy and the Philadelphia Iím not convinced

it was Sternís kind of work. Some of the syntax of the opening movement

seems subtly but unambiguously to elude him. This is not a question

of different phrasal emphases because their accumulation does sap the

movement of motivic strength and for all Sternís agility and intelligence

the movement remorselessly fails quite to cohere. Some passages are

rushed through, others are overemphatic, as if his interpretation is

not yet centred or settled Ė and the result is that some phrases are

not given their full value for all the frequently glorious tonal resources

at Sternís disposal. As a result of all this the conclusion of the movement

is not suitably climactic. I felt much the same in the Adagio Ė magnificent

depth of tone but inadequate engagement with the material and, most

surprisingly for the violinist, he fails to ignite the finale in that

spirit of unstoppable, granitic inevitability that the best performances

generate.

He recorded the Brahms three times, firstly with Beecham,

secondly with Ormandy and the Philadelphia in 1959 and finally with

Mehta and the New York Philharmonic. Here Stern really comes into his

own. Brahms was always one of his strongest interpretations. I well

remember the quizzical look Stern shot the Festival Hall audience on

one of his last London visits after a performance of the Op 108 Sonata

with Emanuel Ax Ė to rather tepid applause the look seemed to say "Not

good enough for you?" With Beechamís big, plush conducting Stern

digs into his arsenal of colouristic devices, his battery of tonal reserves.

There is considerable tonal effulgence in the first movement (though

Beecham can be a little dogged in the tuttis) but when it comes to the

cadenza Stern is truly aloft. The naturalness of his phrasing in the

Adagio is magnificent, his tone superbly equalized; tremendous warmth.

And the finale is properly bracing and alive, technically splendid,

stylistically apt.

No complaints about the remastering or about Graham

Melville-Masonís notes. This disc catches something of the sympathetic

collaboration that existed between both musicians and the Brahms is

certainly a standout recording.

Jonathan Woolf