As with other so-called one-work composers, and what

a misnomer that is, all of them wrote far more than one. Rezniček’s

reputation, if he has one at all, is based on the overture to his

opera Donna Diana. Now having got that over with,

one can assess him. Normally described by his biographers as a modernist,

that also proves to be not the case, for much of his music sounds

like Strauss, Humperdinck, Pfitzner and of course Wagner. Indeed,

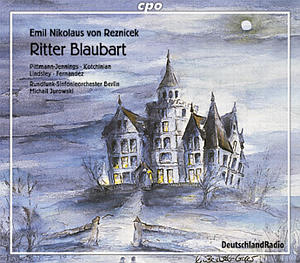

as far as the opera Ritter Blaubart is concerned, it would

not take much to divert into the Ring or Lohengrin

in many places in this attractive work. Rezniček was an exact

contemporary of Mahler, but born where Mahler always aspired to

go (and finally made it too), the Austrian capital, Vienna. Rezniček

died at the age of 85, like Strauss who was four years his junior,

and in the same year as Webern. It is clear from what one hears

here that, unlike Webern, he took a wide berth of the route

adopted by the Second Viennese School and stuck instead to the path

of the classical-romantic tradition. The ‘von’ in his name indicates

an aristocratic background, which gave him a useful headstart when

it came to his education. His grandfather had been a respected figure

in the world of military music. Following his student years, Rezniček

took the Kapellmeister path at small theatres. He was also a military

music director in Prague, where his first three operas had great

success, before settling in Berlin in 1902, and again (for good)

in 1909 after three years in Warsaw.

In 1923 Richard Specht considered Ritter Blaubart

to be the summit of Rezniček’s music, and it’s hard to disagree

with him that this is well-written, solidly crafted music, if

densely scored in places. Count Bluebeard (he ‘actually’ had a

thick, dark, black beard if legend is to be believed) was

famed for his unusual sex appeal and prowess, and was doomed to

bear a destiny which led women into ruin. Such was the attraction

of this tale that one finds settings going back to Grétry

in 1789, followed by Offenbach, Dukas and Bartók, so the

story has lost little of its impact over the years. Rezniček’s

librettist was Herbert Eulenberg, whose play was performed for

the first time in Berlin in 1906, but suffered at the hands of

faction fighting and political intrigue within theatrical circles.

It enjoyed more deserved praise when it reappeared (necessarily

shortened) as the libretto of Rezniček’s opera after its

celebrated premiere in Darmstadt in 1920 conducted by the Hans

Richter-protégé Michael Balling. In Berlin the opera thrived under

Leo Blech’s guidance with 27 performances in the six years

following its first staging there on 31 October 1920.

Though the story is an utterly gloomy one, it

gives wonderful scope for a kaleidoscopic range of emotion and

dramatic situation. Blaubart kills his first wife when he finds

her in the arms of her lover, but then goes on to kill her five

successors because they have dared to enter a room in which his

initial secret is locked. By the time Judith, daughter of Count

Nikolaus, has become his seventh wife, the locked room contains

the heads of her six predecessors. In his absence she is entrusted

with the room’s golden key and, despite being warned not to enter,

disobeys him. Because the key immediately becomes indelibly stained

with blood, the secret is out and she suffers the same fate as

all his other wives. At her burial Blaubart seduces her sister

Agnes, who agrees to follow him back to his castle. Blaubart’s

blind servant Josua seeks to forestall her fate by setting fire

to the castle in an attempt to destroy all the evidence. But this

only serves to make Blaubart confess to Agnes what he has done

to her sister, and, in despair she promptly throws herself from

a balcony leaving Blaubart to perish in the flames.

Melodramatic though this all is, the musical

result is impressive, and the performance here under Michail Jurowski

utterly convincing. All the soloists are more than equal to the

task, some of it as demanding as anything Wagner ever made of

his singers. The orchestral interludes, which frankly contain

the best music (begging the question why Rezniček

never put together a purely orchestral tone poem consisting of

this music) are superbly played by the Berlin Radio Orchestra.

Rezniček now deserves more than to be regarded as the composer

of just one overture, that of Donna Diana, and cpo

has done his cause proud with the release of this opera.

Christopher Fifield

|

Error processing SSI file

|