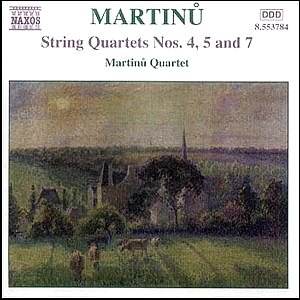

Naxos has quietly been doing a

grand job on behalf of the music of Bohuslav Martinů. We

have two volumes of the chamber music, all six symphonies also

his major choral and orchestral work ‘The Epic of Gilgamesh’ and

now the complete string quartets in three volumes. There is an

element of ‘anorakism’ in us all but it’s worth saying

that if you were to buy that lot, the composer’s most significant

compositions, it would set you back only about Ł40.

These three quartets make strange bedfellows.

The 4th is a typically Czech work. I suppose if Janáček

had lived on into the 1930s he might have written a third quartet

like this. The 5th is a very fine and intense

work more in the style of Bartók; dissonant, aggressive

and rhythmic. The 7th is neo-classical and to emphasise

that it has three movements with a central Andante and a final

allegro seeming to update Vivaldi.

But why do composers

write seven or more quartets? Aren’t there enough in the world?

Martinů was very prolific and sometimes one wonders in certain

works if the composer really had anything to say. The 7th

quartet for me is like that. Its twenty-one minutes is stretched

out into ramblings and note spinning without much point ‘signifying

nothing’, unless I’m missing a point somewhere about music of

the neo-classical era. Martinů’s tendency towards

notespinning is especially noticeable in the immediate post-war

period once he had settled into the security of life in New York.

This is, of course, a very personal view.

The other two quartets are fortunately quite

different. They pre-date the time when Martinů

was driven out of his native homeland by the Nazis in 1940. As

such they have more of the earthy Czech quality we associate with

works like ‘In memory of Lidice’, finished in 1943 but started

well before the war, and the Field Mass (1939). These quartets

are each four movement pieces with typically hard-driven scherzos

full of momentum and wonderful singing cross-rhythms. Each has

a lyrical Adagio slow movement.

Czech dances never seem to be far away not only

in the scherzos but, for instance in the first movement of the

4th quartet written in Paris. This also has a typically

contrasting second subject. The fourth movement likewise "draws

on Moravian and Czech sources for its inspiration". I quote

the booklet notes by a writer who has in common with

Martinů the fact that (for Naxos and Marco Polo at least)

he is wonderfully prolific, Keith Anderson. Not only does he succinctly

write about the composer’s life he also gives us analytical notes

that are helpful and not overly academic. Of the 5th

quartet he tells us that: "political circumstances prevented

its performance in 1939 and that it had to wait until 1958 for

its 1st performance". It is the longest and finest

of the three with a substantial finale, which grows from a suspense

laden Lento into a rollicking Allegro. It must have been very

frustrating for the composer to wait almost twenty years before

he could hear it. But surely Martinů

knew Bartók’s 3rd Quartet of 1927.

I have to say that I have not heard these works

before and I therefore feel unable to criticize the performances

and to draw comparisons. However I must warn purchasers that the

recording seems to be rather top heavy. The cello playing of Jitka

Vlasankova may need to be more decisive and clear being here rather

subsumed within the group. I shall blame the recording for this.

The simple expedient of turning up the bass on the amplifier moderates

the effect.

The quartet players are pictured within but why,

again, has Naxos taken over seven years to release this disc?

Gary Higginson

see also review

by Kevin Sutton