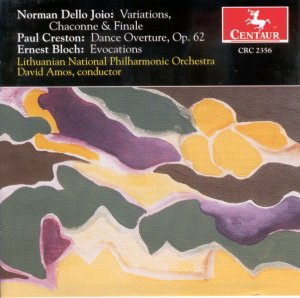

These three classics of 20th century American

music together play for less than an hour.

The Dello Joio is his most accessible

concert work. Originally dubbed Three Symphonic Dances it

was premiered in Chicago by Fritz Reiner. It is the most substantial

piece here. Right from the start it radiates a glow which rises

to what I can best term a cool yet amiable spirituality. Apart

from one vulgar variation which breaks the mood this refrigerated

counterpart to Barber's Adagio works extremely well. The

character is well sustained into the warmer emotional heroics

of the Chaconne where the mood at times touches on Howard

Hanson's and Roy Harris's symphonic style. The Harris fingerprints

are very strong towards the end of the movement especially the

martellato blasts which lift and punctuate the closing

pages leading into the very brief finale - Allegro vivo.

That movement should be thought of in company with the flashing

energy of the Piston Second Symphony finale and Wirén's

Serenade for Strings. This is the first time I have come across

something of Dello Joio's that works as well as say Britten's

Simple Symphony or Janáček's

Sinfonietta. Dello Joio came from a musical family

and when hit by the Depression Norman's dance band supplemented

the family income. In this he was like Benjamin Frankel in London

though the two composers adopted completely different idioms:

Dello Joio kept to his tonal ‘True North’ while Frankel found

sustenance in Bergian dissonance albeit masterfully orchestrated.

Dance is a common thread through Creston's

music. Piece after piece are dance-linked and several of the movements

from his six symphonies are dance episodes. The overture is uproarious

without being vulgar. It has a high rhythmic charge and is good

entertainment music. It is the sort of thing that would go well

with the Kabalevsky Colas Breugnon overture, William Mathias's

ebullient Dance Overture, Alan Rawsthorne's Street

Corner, Bernstein's Candide, Copland's Outdoor Overture

and Arthur Butterworth's still unrecorded Mancunians overture.

It is more than mere high spirits as the poetic idyll of 6.09-9.11

demonstrates. The fairground jerkiness of the end suggests the

composer took his eyes off the ball for a little while and allowed

things to relax into the folksy vigour of Roy Harris's Folksong

Symphony (No. 4).

The Bloch is a serious reflection on Oriental

culture. It began life as Esquisses Orientales in 1930

but after much tinkering and revision over a period of eight years

emerged in its current form. The first movement (Contemplation)

is impressionistic, the second (Houang Ti), as befits a

God of War, rattles and blares with tearing gestures linked

to the saw-toothed fanfares from his 'Jewish' pieces. The third,

Springtime, is a pastoral idyll which resonates with voices

from Ravel's Daphnis et Chloe. Do not look for conscious

or obvious chinoiserie in this music. There is less of that than

in Bantock's delicate Four Chinese Pictures (pretty well

contemporaneous with the Bloch) or the Lambert or Bliss song cycles

of the 1920s.

Good and thoroughly detailed notes by Brendan

Wehrung.

This is a well judged collection. While we may

lament that a couple more works were not added the concert is

a very satisfying one which is likely to win new friends for all

three composers.

Rob Barnett