AVAILABILITY

www.musicandarts.com

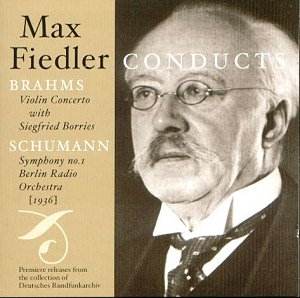

In his judiciously written biographical essay

Mark Kluge aptly notes that Fiedler’s association with Brahms

is not quite as authoritative as some have believed it to be.

It’s true that Fiedler played the piano solo at a rehearsal of

the Second Concerto, at the subsequent concert of which Brahms

was the soloist – but it has always been alleged that Brahms had

heard Fiedler conduct the symphonies and had thus added his imprimatur

to the younger man’s conducting. For this there is no evidence

at all. Though his conducting career began quite late Fiedler

soon began to travel internationally – New York, London – and

was soon appointed Music Director in Boston, a position he held

until he returned to Germany in 1908 and a post in Essen.

That his recordings were relatively few in number

and that so many were of the music of Brahms has led, perhaps

inevitably, to the view that if he wasn’t a Brahms acolyte then

he was, at least, a specialist. He recorded the Second (1931)

and the Fourth (1930) – though the dates given in brackets are

subject to small controversy and may be out by a year – though

not the odd numbered symphonies. The Second Piano Concerto, which

he’d played on that famous occasion so many years before in 1883,

he recorded with Elly Ney in 1939. The Academic Festival Overture

had long before, in 1931, also been recorded. We can now add to

Fiedler’s Brahmsian discography this live performance of the Violin

Concerto with the eminent soloist-leader of the Berlin Orchestra,

Siegfried Borries, then twenty-four. It’s a major discovery for

Fiedler devotees. He opens the first movement slowly, grandly,

with a touch of rhetorical brooding but soon accelerates into

lyrical passages. Indeed his marshalling of the score throughout

is marked by powerful concentration and strong romantic gestures.

His soloist, Borries, was at the early stages of his distinguished

career; indeed had only been leader of the orchestra for a couple

of years. His vibrato can take on a youthful beat from time to

time, sometimes tending toward the smeary; but his eloquently

expressive response to the first movement shows itself in all

sorts of telling little details and the most fundamental is his

vibrato usage. He responds with ardour - but with rather too much

differentiated tone - to the lyrico-expressive demands made on

him by the score. The result is emotive but occasionally too fractured

a response. Fiedler meanwhile offers flexibility and nuance in

support – strong bass accents predominate – whilst Borries’ arsenal

of portamenti are instructively quick but pervasive; he even makes

a downward L-shaped portamento with a very fluttery quality to

it indeed (I liked it but it certainly won’t be to all tastes).

The slow movement has a good oboe solo. Borries

brings his relatively small tone to bear with acumen – he transmits

colour through a coiled tone with a degree of warmth and affection.

I much prefer him to a later Berlin Philharmonic leader now being

touted as the Great German Violinist, Gerhard Taschner. Borries’

reading is affectionate without the aristocratic bearing that

some others bring here. His finale is good – no gypsy abandon,

perhaps, but equally no vulgarity. It possesses verve, which is

important, if more than somewhat undisciplined orchestrally and

the orchestra is not on especially scrupulous form throughout,

it has to be said.

Coupled with the Brahms is Schumann’s First Symphony.

This is a far more contentious reading and to those indifferent

to this kind of performance it will sound maddeningly indulgent.

As with the Brahms it again opens emphatically but it’s also full

of rhythmic retardation and a pervasive, creeping sense of etiolation.

When we reach the eruptive Allegro section of the first movement

we have, so to speak, rhythmically lost our bearings. Tempo fluctuations

abound in the best subjectivist tradition and a sense of almost

wilful late nineteenth century drama. I have to say I didn’t detect

much of a divining thread running through the movement; all I

did find was sectionality even though one can’t but admit the

sonorous and emotive texture of much of the conducting. The slow

movement is again objectively terribly slow. This leads to cumulative

successive peaks of tension and orchestral crisis – tension and

release – but ones that carry with them inherent limitations and

dangers. The expressive depth that is certainly present does become

somewhat compromised by the lack of spine and drive. The final

two movements go considerably – though by no means absolutely

– better. I was glad to hear the performance but it’s one that

I struggled with for some time.

Now for the problem and that’s the sound. Though

it’s stated clearly that this is a release from the collection

of the Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv the sound quality is distinctly

muddy. After a while one’s ear adjusts but there’s a deal of adjusting

to be done. No transfer engineer or process is noted so I rather

wonder how closely this resembles the original in the Berlin archive.

I hope it won’t spoil enthusiasm for the disc which is most eloquent

proof, in the case of the Brahms, of Fiedler’s standing in repertoire

congenial to him and, as it were, him to it.

Jonathan Woolf