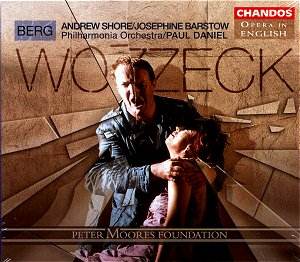

I have to nail my colours to the mast straightaway

and say I am generally of the opinion that opera should be performed

in the language intended for it by the composer. So it is a surprise

(and a happy one) to report that this English language version

of Wozzeck is an almost unqualified success. This is probably

due to two things. One is that the German language lends itself

better than most to being translated into English. The other is

the quality of Richard Stokes’s version, which is intelligent,

literate and, above all, musical.

I have a number of CD versions of Wozzeck

in my collection, as well as two video productions. My long-standing

favourite is Dohnanyi with the VPO on Decca, sumptuously recorded,

superbly played and with outstanding vocal leads. Whilst this

new English version is unique from the language point of view,

it is possible to compare all other aspects, and the Chandos is

not wanting in any major area. I was privileged, in the early

1990s, to see the Opera North production on which this recording

is based and remember vividly being bowled over by Andrew Shore’s

memorable assumption of the title role, as well as Deborah Warner’s

spare, Expressionist production. I was also mightily impressed

by Paul Daniel’s handling of the orchestra. In his hands we were

treated to an almost Straussian richness of sound, a revelling

in Berg’s originality of texture and a keen ear for the longer

line, so that detail did not overtake the bigger picture. Ten

years on, Shore’s performance has matured into something deeper

and even more moving, and Daniel’s conducting has similarly accrued

the kind of authority that puts it up with the best.

Although Wozzeck is an ensemble piece,

it is important that the two main protagonists, the pathetic anti-hero

Wozzeck and his ‘harlot with a heart’ partner Marie, are totally

believable. Some recorded performances (Fischer-Dieskau comes

to mind) rather ham it up, overdoing the sprechstimme and

going over the top in certain scenes, such as the death of Marie.

Andrew Shore strikes me as achieving a near ideal balance of mania,

helplessness and nobility. He is determined that we should not

just feel sorry for Wozzeck’s plight, but that we should understand

the wider social implications – that Wozzeck is a victim of the

system. The very opening sets the scene perfectly; Wozzeck is

shaving the Captain, his immediate superior, who taunts and mocks

him constantly. Wozzeck responds monosyllabically ‘Just so, Herr

Hauptmann’. When we get to the great four-note refrain that acts

as a kind of humanist motto ‘Wir arme Leut’ (usually translated

as ‘We poor folk’ but here set as ‘Wretches like us’, which perfectly

fits the musical pattern), Shore and Daniel broaden the phrase

just a touch, investing it with the kind of dignity that Berg

surely intended. This is one example of many throughout the performance

where Shore illuminates phrases, responding to the excellent translation

with real insight. He does not really let go until the final act,

where he wanders around desperately yelling ‘Murder, murder!’

in a state of crazed panic, yet even here we feel someone should

help him instead of condemning him, as we know would happen.

As Marie, Dame Josephine Barstow gives a performance

of equal depth and sincerity.

At times she doesn’t quite sound common enough,

with a rather cultured ‘opera’ accent apparent in some of the

venomous exchanges with Margret (Act 1, scene 3). But she is unbearably

moving in Act 3, as she reads to her child from the Bible the

story of the adulterous woman. Her exchanges with Wozzeck tingle

with tension. When she finally gives herself to the Drum Major

at the end of Act 1, her delivery of the words ‘Why should I care?

Who could give a damn?’ seem to sum up the whole tragedy of her

pitiful life.

Talking of the Drum Major, there’s a marvellously

bullish portrayal from Alan Woodrow here. He does not shirk from

the extremities of the character, which are here highlighted by

the translation. As he drunkenly assaults Wozzeck in the barracks

(Act 2, scene 5) he pulls no punches with the lines ‘Bas**rd,

shall I rip your tongue from your gullet and wrap it round your

f***ing neck?’ This is typical of a scene where one is shocked

anew at the effectiveness of this piece in English, almost like

hearing it for the first time. All the other characters seem to

relish being able to sing a translation of this quality; indeed,

I was happily able to read through the full text (included in

the booklet) just for the sheer pleasure of the language.

The Philharmonia Orchestra plays superbly, and

though they may not have the razor-sharp ensemble of Dohnanyi’s

Vienna forces, the strings display great tonal weight and the

many instrumental solos have real character. In Daniel’s expert

hands, the famous D minor Interlude, effectively a symphonic summing

up of the opera, has opulence and gravitas and sounds (quite appropriately)

like a miniature Mahler slow movement. Certainly the recording

Chandos gives them helps the aural experience, with superb presence,

clarity and bloom on the sound. Notes are by a staunch supporter

of this Chandos series, the Earl of Harewood, who gives his own

interesting slant on the piece, including his first acquaintance

with it in Boult’s famous 1949 concert performance.

Wozzeck is a relatively short opera and

many, including Dohnanyi, include a filler (in his case, a superb

performance of its spiritual ancestor, Schoenberg’s Erwartung).

There is nothing here, though I understand Chandos are offering

the set at mid-price. This should entice people to try it, for

it certainly provides many new insights and rewards, and makes

comparison almost pointless. Whether you feel (like me) that you

really know the work, I guarantee this is worth hearing, and will

give you a fresh and illuminating perspective on one of the twentieth

century’s most harrowing and original masterpieces.

Tony Haywood