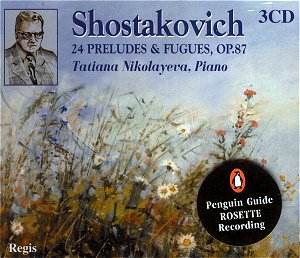

Dmitri Shostakovich’s monumental set of twenty-four

Preludes and Fugues bears much similarity to Bach’s Well-Tempered

Clavier in terms of expression, architecture, mastery of form

and emotional impact. There are two primary differences between

them. The first is that the Shostakovich music is often either

brutal or sarcastic. Secondly Shostakovich progresses his way

through the set using the circle of fifths as Chopin did in his

Opus 28 Preludes instead of employing the sequence of semi-tones

used by Bach.

Shostakovich’s Opus 87 has not received a great

many recordings over the decades. Of recent vintage, there is

only Vladimir Ashkenazy on Decca, Keith Jarrett on ECM, Konstantin

Scherbakov on Naxos, and Boris Petrushansky on the Dynamic label.

Each of these sets is very rewarding, although Keith Jarrett sometimes

appears to have no idea that he’s performing the music of a Russian

composer and not music for the local Hotel lounge.

There is another performer of this music on record,

and she is Tatiana Nikolayeva. Her intimacy and identification

with the work easily overshadows the other artists who have made

recordings. Nikolayeva kept encouraging Shostakovich to finish

the cycle and was also responsible for its State approval and

publication in 1952. Further, she gave the first public performance

of Opus 87 and was even rehearsed by Shostakovich.

If memory serves, Nikolayeva has recorded Opus 87 three different

times. I have not heard the earliest recording but am very familiar

with the 1987 performances as well as the 1990 readings for Hyperion.

The 1987 recordings have traditionally been in the hands of BMG/Melodiya

with reissues and deletions through the years, but Regis Records

has evidently been able to secure a licence for these performances.

My hope is that they will remain in circulation for years to come.

[While you may be able to find copies of the BMG-Melodiya set,

officially it went out of the catalogue two years ago when, it

is understood, BMG were told by the owners that the licence had

expired. Ed.]

I don’t want to make light of other artists in

this repertoire, but Nikolayeva has the inside track. She is the

only one who consistently enters and explores the Shostakovich

soundworld and his struggles to write the music he wanted to without

being sent to the Siberian wasteland. As it stands, this 1987

set only has competition from Nikolayeva’s Hyperion performances.

These are the two that I am comparing for the purposes of the

review.

Overall, I would have great trouble making a

selection between Nikolayeva’s two recordings. The 1987 set has

a primitive and brutal strength, while the Hyperion is more cosmopolitan.

Concerning sound characteristics, the 1990 sound is stark and

a little wet in comparison to the very dry and clinical sound

of the 1987 recordings.

There are too many pieces of music to detail,

so I’ll just mention a few of the preludes and fugues. The Prelude

in E minor is a flat-out masterpiece. Its bleakness and despair

is all-encompassing, although the music eventually modulates to

the key of A flat major as hope rises to prominence. However,

the E minor ends in bitter irony as befits a dictatorship that

had its grip on every aspect of human endeavor. Both Nikolayeva

versions are exceptional, but I do prefer the 1990 performance

for its more intense bleakness.

The Prelude in D major is a delightful piece

of child-like wonder. Playful arpeggiated chords contrasted by

a consistent bass line project a pristine quality of complete

innocence. Again, the two Nikolayeva versions are superb, particularly

in the right hand projection. The D major Fugue is also playful

but conveys a maturation process that is robust and full of energy.

Here the earlier Nikolayeva possesses the greater energy helped

significantly by her incisive sequence of repeated stuttering

notes.

The 1987 performance of the Prelude in B minor

is an absolute triumph. This is very strong music that depicts

in my mind a hero who is being subjected to and beaten down by

the Soviet system. The piece has an ‘industrial strength’ element

that Nikolayeva plays to the hilt, while her most recent effort

is a tad sluggish. In the B minor Fugue, our hero has learned

humility and wisdom, now being in a much better position to combat

oppression. Both Nikolayeva performances extend to over 7 minutes

and offer a full-course meal of emotional content and shadings.

The Fugue in B flat minor is a most interesting

piece as Shostakovich takes us to a freely floating environment

as if gliding through outer space. However, the long coda transfers

us to the key of B flat major where a beacon of light shows the

way to the security of home. Nikolayeva’s outstanding performance

is transcendent in the coda where she gives me the most positive

feeling of finding home after the free-fall.

The Prelude and Fugue in E flat major is another highlight for

the 1987 set. The Prelude alternates an heroic chorale with a

satirical caprice. At the conclusion, the two sections meld into

one. Nikolayeva’s most endearing trait here is how well she invests

the caprice with an exquisite ‘music-box’ sound. The Fugue is

loaded with chromatic inflections and gives me the image of a

person attempting to climb out of a hole but always losing ground.

Nikolayeva is riveting with her stern demeanor and intricate display

of the chromatic elements.

For music depicting humans out of control, the

Prelude and Fugue in B flat major is essential listening. In the

Prelude, running semiquavers have center stage and keep pestering

the bass line. In the Fugue, everyone is emotionally scattered

and hyper with no idea of what they are doing. Nikolayeva’s 1987

readings have ambiguity and confusion written all over with a

vivid sense of irony. Her 1990 performance of the Prelude is a

little too soft-grained for my tastes.

In the Preludes and Fugues in G minor and F major,

both Nikolayeva efforts eclipse all alternatives. They are much

slower than the competition, and the measured tempos allow them

to convey fantastic detail and emotional depth and nuance.

The final series is in D minor, and Shostakovich

makes a majestic exit. This series conveys just about every emotion

encountered in the previous keys and seems to provide a history

of living under the Soviet juggernaut. Again, the Nikolayeva twins

have no peers.

I am sure that I can verbally provide just a

small percentage of the full measure of Shostakovich’s masterful

Opus 87. You must experience it for yourself, and Nikolayeva is

the only sure means to reach a significant understanding of Shostakovich’s

psychology, astounding architecture, and the outside forces that

permeate his music.

The only issue remaining is whether the remastering

effort by Paul Arden-Taylor on the Regis set results in better

sound than for the Melodiya transfers. Arden-Taylor gives the

music a darker and richer tone that appears more appealing initially,

but with time one notices a slightly constricted quality; in comparison,

the Melodiya sound blossoms. I see little point in buying the

Regis set if you already own the Melodiya.

In conclusion, those of you who don’t have a

Nikolayeva set of the Shostakovich Opus 87 Preludes and Fugues

need to get at least one. I feel that both the music and performer

transcend classical music categories, making it a simultaneously

uplifting and draining experience for all listeners. Opus 87 is

timeless and one of the masterworks of the classical repertoire.

In Tatiana Nikolayeva, we have the perfect champion to guide us

through Shostakovich’s unique musical labyrinth. Do keep in mind

that listening to the set once or twice will reveal only a small

fraction its worth. I still hear new ideas and connections after

many years of frequent exposure.

Don Satz