Stainerís Crucifixion is a work at which

it is easy to turn up oneís nose from what we like to think is

the sophisticated standpoint of the twenty-first century. Having

taken part in a number of performances of the work, both as a

member of the choir and as a soloist I do not subscribe to that

view even though I readily acknowledge that the work has its weaknesses.

It is true that the libretto can seem awkward and full of conventional

Victorian piety. However, as Barry Rose points out in his informed,

understanding note, the librettist expressed himself in the liturgical

language of the day. I do wonder, however, if it would have been

better if the libretto had been fashioned from the words of scripture.

As, for example, Elgar did in Apostles and Kingdom.

Perhaps it is not without significance that perhaps the most enduring

part of the work, ĎGod so loved the worldí sets words directly

taken from St. Johnís Gospel.

The music is also sometimes patronised these

days and it is true that Stainer breaks no new harmonic ground.

However, the sincerity of the piece is never in doubt. I think

one needs to take the music on the level that it is offered and

to acknowledge that its sustained popularity among English choirs

must count for something.

It is worth recalling the genesis of the piece.

Stainer, who was then in charge of the music at St Paulís Cathedral,

wrote it for the choir of another London church, Marylebone Parish

Church. Given that these days many English churches are struggling

to maintain any kind of choir, it is salutary to learn from Barry

Rose that the Marylebone choir of 1887 consisted of 30 men and

no less than 60 boys (altos and trebles.) The choir, which also

boasted salaried tenor and bass soloists, rehearsed every day

and a contemporary report stated that it was not uncommon for

the choir to attend up to 15 practices and services each week!

So, this wasnít, perhaps, a typical parish church choir. However,

Stainerís not inconsiderable achievement was to compose a cantata

which would be within the compass of most decent parish church

choirs of the day, even if they had to import soloists. The model

was, quite clearly, the passions of Bach Stainer had introduced

the St. Matthew Passion into Holy Week liturgies at St.

Paulís in 1873, within a year of taking up his appointment as

organist there. On a smaller scale, Stainer followed Bach in giving

his soloists a mixture of recitative and reflective arias while

the chorus commented on the action and also took part in it. Finally,

Stainer, like Bach, assigned a role to the congregation through

the interpolation of a number of newly composed hymns, which were

the equivalent of Bachís chorales. Stainer opted for organ accompaniment,

not least, Iím sure, because he envisaged his work being performed

in churches as an adjunct to Lenten liturgies. In this form Crucifixion

has been performed by countless church choirs and choral societies

every year since 1887.

I must say I was a little perturbed to find that

this recording was in a new orchestration by Barry Rose. It concerned

me that orchestral dress was bound to change the essential nature

of the work and make it into an inflated concert hall work, something

which it emphatically is not. In the event I need not have been

concerned at all. Yes, the use of an orchestra inevitably imparts

a different character to the work. However, Rose has done his

work with such skill, sympathy and understanding that the result

is never less than convincing. Indeed, while most performances

of Crucifixion will remain the preserve of organists (and

rightly so), Barry Rose has added a new dimension and I sincerely

hope his orchestral version will be taken up and widely performed.

He has not departed radically from the original

musical text apart from the addition of a few passing notes and

the odd timpani roll. What he has done, however, is to play on

the orchestra as a resourceful organist would do by using different

stops, to create a palette of different colours in the accompaniment.

One particularly good example of this is the fairly lengthy introduction

to the chorus ĎFling wide the gatesí (track 3) where the melody

moves from one instrument to another and each time the baton is

passed, so to speak, the change is seamless yet introduces a subtly

different dimension of colour. He does throw in some tiny brass

fanfares during the big tenor aria, ĎKing ever gloriousí (track

7) but I donít find this intrusive and, indeed, his judicious

use of the brass in this number adds an extra touch of resplendence.

Another particularly ear-catching passage is the bass recitative

"There was darkness" (track 16, 0í59") where I

find the sepulchral bass rumblings in the accompaniment work much

better in orchestral guise than when confined to the pedals of

the organ, as is usual.

Although not precisely detailed in the booklet

I think the orchestration consists of strings, single (?) woodwind,

horns, trumpets, trombones and timpani. The organ still makes

an important contribution to the proceedings. Perhaps itís not

too surprising that Barry Rose should have orchestrated the work

so well for he must be very familiar with it as an organist and

conductor. Indeed, he recorded the work many years ago when he

was organist at Guildford Cathedral and that recording, using

the cathedral choir, has recently reappeared on the Classics for

Pleasure label, though Iím afraid it is yoked in a double CD release

with Maunderís Olivet to Calvary. Now thereís a work of

conventional Victoriana, by the side of which Crucifixion appears

as a towering masterpiece!

Barry Roseís orchestral version of Crucifixion

was commissioned by the Guildford Philharmonic Orchestra and

its first performance took place in Guildford Cathedral on 31

March 2001, the centenary of Stainerís death. This recording,

I imagine, uses pretty much the same forces and both composer

and orchestrator have been well served by the performers. I believe

that the orchestra is at least semi-professional. I spotted a

couple of familiar names in the list of personnel. The playing

is uniformly excellent. The players are sensitive to dynamics

and rubato of which there is quite a bit, not all of it marked

in my score but itís always convincingly done. They never overdo

things. The choir too excels. Twenty-nine singers are listed.

Once again, I suspect that there is at least a leavening of professionals

and by the sound of things the singers are mainly young; they

certainly sound young. Their tone is fresh and focused, there

is abundant evidence of attention to detail and the singing is

bright and committed. The small male solo roles are very well

taken by choir members, as Stainer directs. The choir sings the

hymns. In performances I think itís desirable to cut a few of

the verses in the longer hymns (ten verses of ĎCross of Jesusí

on track 5 is rather a lot even though it is a good tune) but,

clearly a recording must be complete. Rose varies the accompaniment

intelligently and assigns some verses to different sections of

the choir so as to provide welcome and necessary variety. I hope

the sopranos and altos wonít be offended if I say that I especially

enjoyed the verses sung by the men in unison.

It is unfortunate that the workís Achilles heel

lies in the choruses. One of them, ĎGod so loved the worldí (track

9) is very fine, deserving of its popularity as a separate anthem.

Itís splendidly done here. However, the other two "big"

choruses, ĎFling wide the gatesí (track 3) and, even more so,

ĎFrom the throne of His Crossí (track 18) are very much the weak

links in the piece. Both are terribly repetitious and Stainer

stretches thin musical material a very long way. If both had been

half as long as they are it would have been much better. Not even

the good performances they receive here can convince me that either

has much musical merit, Iím afraid.

What of the soloists? Iím not entirely convinced

by tenor, Peter Auty. He has a good voice but aspects of his delivery

trouble me. I find some of his vowel sounds jar somewhat (for

instance track 7, 2í02", at the words "Thou Son of God".)

I felt that there was just a trace, but a discernable and (for

me) distracting one, of an Italianate, operatic hue to much of

his singing. It was only later that I read in his biography that

he has done a good deal of opera. Iím afraid I donít find much

sweetness in his tone and, while there must be an heroic ring

(especially for ĎKing ever gloriousí) the type of voice I think

Iím looking for in this role is the lighter more "traditionally

English" tenor voice, as exemplified by, say John Mark Ainsley.

This, of course, is a wholly subjective view and other listeners

may well form a different, more positive opinion.

Roderick Williams is another matter. He has a

firm, well-focused baritone, which he uses with great intelligence.

Coincidentally, Iíve just been listening for pleasure to the new

recording of Dysonís Quo Vadis to which he makes a telling

and fine contribution. He uses vocal colour imaginatively but

by no means excessively. Indeed, he seems to have realised that

the best way to sing the solo roles in this work is in a straightforward

way with sincerity and directness, resisting the temptation to

try to "do" too much with the music. His is a dignified

and thoroughly musical performance which I appreciated very much.

Iíve said a lot about Barry Rose as orchestrator

but little about his conducting. I mean it as a compliment when

I say that one scarcely notices the conducting. He is clearly

the master of the score and he keeps things on a tight rein, injecting

pace and vigour where necessary but also not afraid to use rubato

to underscore key points. His is a fluent and idiomatic reading

of the piece. His direction, allied to the addition of orchestral

colouring, relates the work more closely than I had previously

realised to Elgarís early cantatas (though those contain better

music.)

The recorded sound is first rate, being clear

and well balanced. Presentation is good. The full text is provided

and, as I said earlier, Barry Rose contributes an excellent, readable

essay about the work itself and the background to his orchestration.

Hearing Stainerís piece now in an orchestral version makes me

wonder why the task has not been undertaken before. However, now

that it has been done I can report that it is hard to think that

it could have been done more successfully or with greater sympathy

and sensitivity. Barry Rose deserves congratulations on a fine

achievement and it is to be hoped that more performances will

follow.

This is a very good CD which I warmly commend

to all lovers of the English choral tradition.

John Quinn

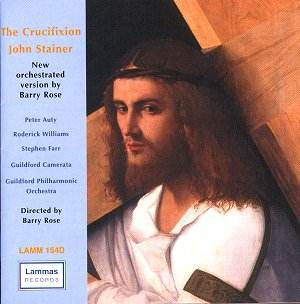

![]() orch. Barry Rose (2001)

orch. Barry Rose (2001)

![]() LAMMAS LAMM 154D [67í34"]

LAMMAS LAMM 154D [67í34"]