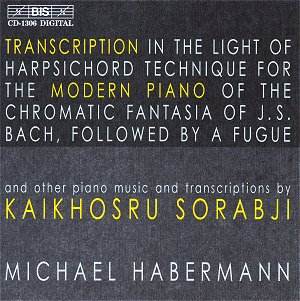

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji was one of the great individuals

of music. His magnum opus, the Opus Clavicembalisticum, still

inspires awe and not a little fear in the hearts of all sane pianists,

and remains his most (in)famous work (Geoffrey Douglas Madge recorded

this on BIS CD1062-4).

On this disc the pianist is Michael Habermann,

who specialises in Sorabji’s music and has given a number of first

performances (he also provides fascinating liner notes). As a

labour of love this can hardly be bettered, for the 1 hour 8 minutes

playing time is gripping from first note to last.

One would have thought that Ravel’s Rapsodie

espagnole was heady enough, but obviously not for Sorabji

(Habermann quotes a letter in which Sorabji also refers to a transcription

of the Closing Scene of Richard Strauss’ Salome … now that

I would like to hear). The Ravel/Sorabji Rapsodie espagnole

was premièred by Habermann in Stockholm in 1998 and is

required listening. Sorabji takes Ravel’s individual sound-world

and filters it through his own, so that Ravel’s harmonies become

more cloudy than veiled, eventually becoming more and more obscure

and tending towards clusters. The finale, ‘Feria’, is tough in

the extreme. Habermann responds with breathtaking aplomb. This

is such an exhilarating performance, I suggest the listener takes

a break after it!.

Habermann refers to the Passeggiata Veneziana

as, ‘one of Sorabji’s greatest compositions’, stating that, ‘it

is the most challenging of the transcriptions in that the original

material serves as a springboard for fantastic escapades’. It

certainly is no walk-over of a piece, but complementing the virtuosity

of the notes is the virtuosity of the composer, whether in the

stellar evocations of the opening or in the emergence of the theme

(the ‘Barcarolle’ from Offenbach’s Contes d’Hoffmann) from

decadently perfumed harmonies. It is typical of this composer

in that over-the-top technical complexities (in the ‘Tarantella’

section) are immediately juxtaposed with extremely decadent passages

(the tempo/expression mark in the latter part is, ‘Notturnino.

Sonnolento, languidamente voluttuoso. Sonorità sempre piena

e calorosa’).

The solo piano version of Variation 56 from the

Symphonic Variations is based on the ‘graveyard’ finale

of Chopin’s Second Piano Sonata (1839). The same ominous movement

is there, but ‘opened out’. This is more of a transformation of

Chopin than anything else and makes for tremendously exciting

listening. Given Sorabji’s penchant for extremes, it should come

as no surprise that the Quasi habanera is really quite

sleazy.

The Bach/Sorabji item shows a firm and confident

hand at work (the fugue that follows the Chromatic Fantasia,

referred to in the title, is the D minor, BWV948). Habermann is

particularly successful in projecting the fugue’s granite-like

sonorities.

Finally, the Pasticcio capriccioso on

Chopin’s Op. 64 No. 1. It is difficult to top Habermann’s own

commentary: ‘Embellishment and added-note harmonies assume mammoth

proportions. The ending of the Pasticcio is almost catastrophic

in nature’. It is an ideal way in which to end the disc, exuding

style and humour whilst simultaneously prickling with difficulties.

BIS are to be congratulated on their adventurous

programming. This disc may immediately seem to be for pianophiles

only, but in fact it offers a fascinating window into Sorabji’s

unique world.

Colin Clarke