I have long been a frustrated admirer of Jongenís

music. Although it has always been widely appreciated, it has

been too rarely heard and recorded in the many long years after

his death in 1953, of which 2003 marks the fiftieth anniversary.

Now, at long last, it is slowly being given its due, at least

as far as recordings are concerned. Performances in concert or

recital are still a rare event, even in Belgium. Things, however,

are now on the change and this rehabilitation should go on throughout

2003. At the very least Jongenís representation in the record

catalogue will be greatly improved by the end of the year.

His considerable output includes many piano works,

often substantial ones, of which a mere handful has remained in

the repertoire. The present double-CD set, actually the first

volume of Pavaneís recording of his complete piano music, is a

real eye- and ear-opener. It has often been taken for granted

that Jongen only composed short, impressionistic miniatures, such

as the popular Two Pieces Op.33 or the neo-classical

Sonatina Op.88. That he never composed a full-fledged

piano sonata seems to have ruled him out as a serious composer

of piano music. He nevertheless composed piano works throughout

his long career. He was a gifted pianist who regularly played

in concerts. During World War I, he settled in England and founded

the Quatuor belge de Londres with, among others, Lionel

Tertis. His first opus was a Concerto symphonique Op.1

for piano and orchestra composed in 1892 (he was nineteen!) and

his last piano work Mazurka Op.126 bis dates from

1943. However he went on writing several pieces for piano duet

until 1950. His pieces for piano duets and two pianos will also

soon be available in brand new recordings to be released shortly

by Pavane.

Jongenís natural lyricism is always counterbalanced

by formal clarity, harmonic subtlety, refined elegance and some

earthly directness inherited from his Ardennes origins. His musical

gifts are expressed in healthy, straightforward dance rhythms

redolent of folk song, although he rarely quotes folk material.

His piano music perfectly sums up Jongenís musical make-up and

ideals. These were, for him, articles of faith which he stuck

to regardless of fashion. This may account for the neglect into

which his music plummeted after his death. His music, as with

that of Moeran or Ireland, may be eclectic in its various influences

but, just as Moeranís or Irelandís, it is unmistakably personal.

The earliest work here is the reasonably popular

diptych Two Pieces Op.33 of 1908 (Clair de lune

and Soleil à midi) which made much for Jongenís

reputation in the early 20th Century. In spite of whiffs

from Debussy or Ravel, the music brilliantly demonstrates Jongenís

idiomatic grasp of the instrumentís possibilities. The Deux

rondes wallonnes Op.40 of 1912, which he also orchestrated

as he did the Two Pieces Op.33 and the Petite

Suite Op.75, have long been quite popular (probably more

so in their orchestral guise). Both are based on Walloon folk

songs and the second round rhapsodises on a well-known cramignon

from Liège. The cramignon is a round dance related

to the French carmagnole. Crépuscule au Lac

Ogwen Op.52 was composed during his stay in England, as

was his Danse lente Op.56 for flute and harp or

piano. The Op. 52 work is an atmospheric miniature of the kind

that Ireland or Moeran might have written. In fact, Jongenís piano

music has much in common with that of these composers. Though

he never composed a traditional "grand" piano sonata,

Jongen nevertheless came near to it when he composed one of his

first major piano works, the substantial Suite en forme

de sonate Op.60. This is a real sonata in all but name,

in spite of the somewhat misleading titles of the movements: Sonatine,

La neige sur les Fagnes [a region in eastern Belgium where

Jongen owned a summer cottage], Menuet dansé and

Rondeau. The opening Sonatine pays homage to Scarlatti,

whereas La neige sur les Fagnes is a beautifully atmospheric

reverie, of which the dreamy mood is soon dispelled by

the elegant Minuet. This major work ends with a lively Rondeau,

a joyful, energetic peasant dance. As so many works with a similar

title, Petite Suite Op.75, which also exists in

orchestral guise, is music for children. Nevertheless this is

quite demanding on the pianistís part. It is a suite of colourful

vignettes conjuring up childrenís games and dreams. It is one

of his most appealing works with more than a touch of delicate

humour. The Neo-classical Sonatina Op.88 is probably

his best-known piano work, or Ė at least Ė the one that has secured

a permanent place in the repertoire. Quite deservedly so for its

brevity encompasses all major Jongen hallmarks Ďin a nutshellí.

The three Impromptus, Op.87, Op.99

and Op.126 No.1 (the latter his penultimate piano

work) were written at various periods of Jongenís prolific composing

career. All three are free fantasies of almost improvisatory character

and of great melodic charm. The 24 petits préludes

dans tous les tons Op.116, composed during the war years

in 1940-1941, are short character studies of great variety, never

outstaying their welcome. They are in turn dreamy, playful, tender,

lightly dancing, paying passing homage to Chopin (No.17) and to

Scarlatti (No.22) or greeting his daughterís third birthday (No.9).

The whole set is capped by a lively and brilliant Toccata-fanfare

of great verve followed by a peaceful, song-like epilogue (No.24

Pour conclure). This is another major achievement far transcending

the implied didactic purpose its title might suggest.

Diane Andersenís richly varied tonal palette,

effortless technique and poetic insight are ideally suited to

Jongenís superbly crafted, subtly varied and appealing music.

This is a real must for any Jongen lover. I am eagerly awaiting

Volume 2 and the opportunity to hear more of his music.

Hubert Culot

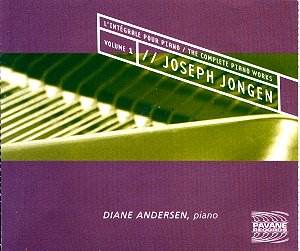

![]() Diane Andersen (piano)

Diane Andersen (piano)![]() PAVANE ADW 7475/6

[70:29 + 76:56]

PAVANE ADW 7475/6

[70:29 + 76:56]