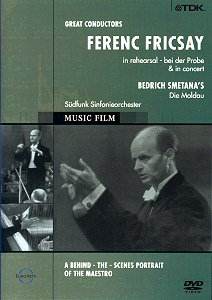

A relatively short while ago, I heard a well

known critic, who should have known better, describe Ferenc Fricsay

as an unknown conductor who was only now starting to get his just

recognition on disc. Did he not realize that in the 1950s and

1960s Fricsay vied with both Furtwängler and Karajan as DGG’s

primary conductor? How reputations are lost or dimmed with the

passing years. Full marks to TDK therefore for making this recording

available to us. Full marks also for making available the actual

performance resulting from these sessions.

As is common with this Great Conductors series,

the sound is reasonable broadcast quality mono sound with black

and white pictures. When this film was made in 1960, Fricsay was

only three years away from death, and the sight of the conductor

forcing his weakened body to obey his musical inspiration is most

moving.

He looks to be in very poor health as he rehearses

the orchestra, but quite soon, we forget his physical condition,

so intense is the musical inspiration and concentration from both

conductor and orchestra. One can hear very clearly how the performance

develops from shaky start to confident luxurious playing at the

end of the rehearsal. This time, we also get to hear the performance

in the concert hall and experience the reaction of the audience.

This material has been released before on CD as a bonus disc issued

by DG in their Ferenc Fricsay Portrait series. This was part of

a 10 disc set, no longer available, which cut a swathe though

Fricsay’s favourite composers. I wonder how many of you will remember

his absolutely superb performance of Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique

Symphony, long a first choice in the catalogue.

Fricsay, Hungarian by birth, spent most of his

active conducting career in West Germany. He conducted the Berlin

Philharmonic regularly, and was Chief conductor of the RIAS Symphony

Orchestra, Berlin, then to become the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra.

His mainstay characteristic was to urge his players to listen

to each other, and to concentrate on a chamber music style of

playing. This becomes clearly evident in the rehearsal. The result

of this was a delicacy in his interpretations and a wonderful

balance within the orchestra. He must have been a recording engineer’s

dream, similar to Sir Adrian Boult, who had a similar outlook

in relation to internal orchestral balances.

He was a superb Mozart conductor and what I find

incredible, given the pace of the period bands’ interpretations,

is the criticism of Fricsay’s Mozart opera performances that the

tempi are generally too fast. One is never satisfied!

His interpretations of the music of his compatriots,

Bartók and Kodaly have long been admired, and it is this

chamber style of playing that brings out the different strands

of the writing so clearly – none of the slow romantic mush which

disfigures many of the modern interpretations of these works.

Back to the current issue – there is a very moving

part of the rehearsal where Fricsay turns to the orchestra and

says "You know gentlemen, it is very good to be alive".

This is almost a cry from the heart of a very passionate interpreter

of Ma Vlast. More please, if there is any more from this

artist, hopefully now better known as a result of this very welcome

release.

John Phillips