This was chosen as Recording of the Month

last month - see review

EMI are to be congratulated on such adventurous

programming, teaming these relatively lesser known concertos.

It would have been so much easier and probably more commercially

appealing to have recorded Walton’s much better known and more

immediately appealing Violin Concerto rather than the one for

Viola. But as Malcolm Macdonald says in

his erudite booklet note, we have the opportunity to compare these

two concertos. Although written ten years apart, they were composed

when the two men were in their early twenties (Britten was, 26;

Walton 25). Both follow a strikingly modern pattern, which had

been used by Prokofiev for his First Violin Concerto of 1916-17.

This broke the tradition of the great Classical and Romantic concertos.

Both concertos follow a similar format: a moderately paced, predominantly

lyrical first movement, a highly rhythmic central scherzo and

a substantial, far lengthier (Britten, 15:10; Walton, 16:23 here)

wide-ranging finale that sums of the argument of the whole work.

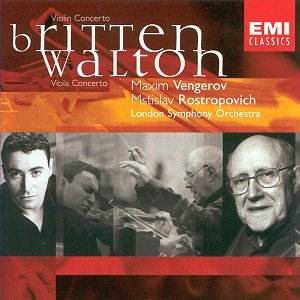

Clearly the idea of the

partnership of Maxim Vengerov and Mstislav Rostropovich is a powerful

one. With producer John Fraser in the control room they do not

disappoint. Nice that Fraser gets a prominent credit on the album

after many years of excellent service for EMI supervising so many

excellent recordings.

Britten began work

on his Violin Concerto in 1938 and completed it a few days after

World War II broke out. It was premiered in New York on 29 March

1940 by the Spanish violinist Antonio Brosa, a refugee from Franco’s

regime. The New York Philharmonic Orchestra was conducted by Barbirolli.

Britten had met Brosa in the mid-1930s and had performed with

him in the Barcelona in 1936 shortly before the outbreak of the

Spanish Civil War. Appropriately, Britten uses Spanish rhythms

and spectral hints of flamenco. The frequent restlessness and

harsh voice of the orchestra, with, for example, its persistently

nagging drum rhythm surely reflects the growing international

tension of those days. The violin sings serenely, pacifyingly,

then ultimately in lamentation.. Vengerov’s beautifully refined

and eloquent reading explores depths of emotional involvement

while he shows his usual quicksilver dexterity in the wild sardonic

scherzo. Both conductor and soloist point up the Prokofiev inspiration

of this movement. Throughout, Rostropovich provides a very colourful

and dramatic accompaniment with the orchestral tapestry nicely

balanced and transparent.

It was Sir Thomas Beecham

who suggested, in 1928, that Walton should write a Viola

Concerto for Lionel Tertis. Christopher Palmer commented, "It

was a work of such obvious mastery that it established Walton’s

place in the vanguard of contemporary English music." At

the time, however, Walton confessed that he knew little about

the viola except that it made a rather awful sound! Nevertheless,

he rose to the challenge and completed its composition at Amalfi

south of the Bay of Naples. Alas, Tertis, returned it declaring

it too modern. Understandably, Walton was deeply hurt. However

the German viola player and composer Paul Hindemith agreed to

premiere the Concerto. Tertis later apologized to Walton for having

turned the work down and requested further performances of the

work. In 1961 Walton revised the score reducing the size of the

orchestra using double (rather than triple) woodwind, eliminating

one trumpet and the tuba, but adding a harp. This is heard mainly

in its lower registers to balance the viola adding a gentle anchoring

ostinato, and heard most affectingly in the final Allegro moderato

movement as a lovely ostinato figure. This might suggest lapping-water

and, combined with the brilliant surrounding orchestral texture,

conveys the colour and light of a Mediterranean coastline.

For this recording, Vengerov

uses a Stradivari ‘Archinto’ viola of 1696 lent by the Royal Academy

of Music, London from which he produces the most beautiful tone.

I cannot remember this concerto’s sweet sad lyricism and romantic

yearning more movingly communicated. The mercurial Rondo with

its perky syncopations has attack and brio aplenty. Overall Vengerov

and Rostropovich give a deeply satisfying reading, rising, with

aplomb, to the Concerto’s challenges typified by wide intervals,

looping arabesques, and irregular and syncopated rhythmic patterns.

Memorable and deeply satisfying

performances of two major British string concertos. Unhesitatingly

recommended.

Ian Lace

See also review by

Marc Bridle