In general I like transcriptions of Bach, especially

when they give us a "new" concerto for a previously

neglected instrument. And I am particularly pleased to see more

investigation of the place of the lute/guitar in the works of

J. S. Bach as I feel that these instruments and Spanish music

in general played a greater part in his musical æsthetic

than has been heretofore generally acknowledged.

Sharon Isbin was studying rocket science when

she made her public performance debut at the age of 14 in Minnesota.

The experience was so positive she changed careers and went on

to study Bach with Rosalyn Tureck for ten years, and is now head

of the guitar department at Juilliard School of Music.

You may be asking what Tureck has to do with

the guitar. Others, including myself, are asking what Tureck has

to do with Bach; although I was able to enjoy Tureck’s recent

Goldberg Variations recording by taking advantage of the

option offered on the CD to speed up the performance. In general

I do not care for her Bach performances and disagree with her

written comments.

Miss Isbin’s approach to the guitar is to emphasise

choppy phrasing and to attempt the greatest possible dynamic range

on the instrument. Loud notes are plucked so strongly that at

times they squawk annoyingly, while the quietest notes are brushed

with the finger so lightly that they are barely audible above

the finger noise. This range is put at the service of an exaggerated

‘original performance practice’ aesthetic which greatly accents

phrases, resulting in a jerky, at times actually stumbling, forward

motion. Add to this a sympathy with Tureck’s ‘I’ve got a secret

I won’t tell’ philosophy towards Baroque ornamentation, namely

that there was a secret code known to all baroque keyboard artists

and to no one else. This secret is said to have dictated an absolutely

correct ornamentation to each phrase of the music, which was then

to be played this way at all times and under all circumstances.

Needless to say, I don’t believe it, and I don’t feel that the

results heard here reinforce the philosophy.

Ornamentation in the Baroque was a personal communication

from the performer to his or her audience. Apart from frequent

application of a few generally agreed stylistic conventions, ornamentation

was strictly a matter of the occasion and would be different from

one performer to another, from the same performer on different

instruments, and from the same performer and instrument on different

occasions. Any strict canon of ornamentation, including written

tables from the baroque period or carefully written out ornamentations

on specific baroque and earlier manuscripts, are in all cases

to be taken as advisory only. They are to be considered by the

performer as optional and as subordinate to his or her informed

judgement and musical taste. Ornaments should enliven a performance,

add grace, verve, energy, tears, sighs, a little showmanship,

maybe even playfulness.

Of course we must not make the mistake of allowing

what a musical performer writes to affect our perception of the

musical performance at hand, any more than we should consider

an actor’s politics when we enjoy live drama. Tureck’s ornamentation

of a musical phrase expresses her own taste and judgement, and

should be accepted as such wherever she says she got it from,

and the same in regards to her students. The sins of the teacher

should not irrupt into our perception of the student’s work. So

if Isbin’s ornamentation sounds like something she got out of

a book, and it does, it has to be considered to be her fault and

no one else’s. She chose the book, and she can open it or close

it at will.

The most successful performance on the disk is

the Albinoni. Since this work is usually played with gushing,

passionate sentimentality, a relatively crisp version as we have

here is a refreshing change. The Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring

is done smoothly; here the strong phrasing adds passion without

sentimentality and the embellished guitar part adds interest.

This is the only version of this chestnut I could actually recommend

to anyone. I would really like to hear Isbin play an arrangement

of the Aria from Bach’s Orchestral Suite in D, BWV 1068.

If she brings this off as well as I think she would, she could

make Thurston Dart sit up in his grave and start applauding. Her

performance of the Bach Lute prelude BWV 999 does not involve

antic phrasing or routine ornamentation, and comes across directly

and pleasantly, with a total absence of distracting finger noise.

But one misses the energy and drama one finds in Lindberg and

Bream.

The Concerto BWV 1041 is disappointing, perhaps

mostly due to recording perspective. Comparing it to Simon Standage

and Trevor Pinnock, as far along the ‘original performance practice’

scale as I’m prepared to go, Isbin/Griffiths intrude with gratuitous

accents that add nothing in drama. During the tutti passages

the guitar’s loud notes obliterate the orchestra, while the quieter

notes in the same phrase disappear. During the solos, the guitar

is merely a little too far forward. The slow movement is much

more successfully balanced, tempi and ornaments are well chosen,

but the orchestra is still just a little too bouncy. Again, in

the final allegro assai the soloist would have been better

advised merely to double the strings during the tutti passages,

rather than insisting on having something to say at every moment.

The Vivaldi Concerto R 93 is played extremely

well and very enjoyably by both Bream and Isbin. Bream plays on

a lute with a small group of soloists, achieving a real chamber

music feel, although at times the harpsichord is too prominent.

His performance of the slow movement is breathtakingly beautiful.

Isbin plays in front of a string orchestra and in both Vivaldi

works gives us a fully ornamented repeat in the slow movement.

The difference is almost intangible, with Bream giving us a focused

intensity and Isbin being more scholarly. Isbin’s concentration

during R 82 is less than during R 93. What did I say above? Just

a little more straightforward musicianship and less acrobatics

and research would be an improvement.

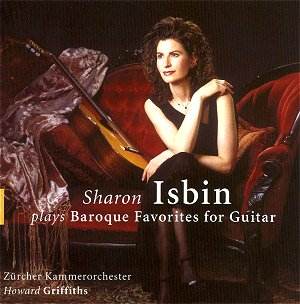

As I am probably too fond of saying, when I was

a kid all the world’s great string players were ugly old Jewish

men with beautiful souls. Now more and more virtuoso string performers

seem to be pretty girls, or at least attractive women, and the

CD packages are graced with ‘friendly’ pictures which seem to

be getting a little more intimate each time. I have the feeling

that if this trend continues we are not far from our first nude

centerfold in a CD booklet.

Paul Shoemaker