The forthcoming 2003 Proms season will see the

British premiere of Kalevi Aho’s Ninth Symphony although

his extraordinarily wide ranging symphonic cycle has in fact now

reached twelve, the latest addition, Luosto Symphony, for

large orchestra, chamber orchestra, eleven "mountain musicians"

and two singers, being scheduled for its first performance on

the slopes of Luosto mountain in Lapland in August 2003.

Like the Ninth Symphony, which features

a concertante part for solo trombone, the Third Symphony

is a hybrid symphonic concerto. Aho did indeed start out with

the intention of writing a violin concerto before he realised

that the piece was taking him in a slightly different direction.

What we have therefore is very much a successful amalgam of the

two forms, a work of considerable technical virtuosity for the

soloist underpinned by an impressive sense of symphonic and organic

structure that is capable of being heard clearly upon first acquaintance.

In terms of language it is the ghost of Shostakovich that is most

clearly evident, an influence that the composer freely acknowledges.

Mahler is also evident on occasions and so, not surprisingly,

is Sibelius. Even at this relatively early stage of his career

however (he was only twenty two when he started work on the symphony)

Aho is able to weld these influences into something that is his

own, at the very least a work that demonstrates a powerful musical

imagination at work.

Cast in four movements, the first is predominantly

preoccupied with the soloist who enters after a quiet opening

passage on percussion. A freely elegiac melody slowly gains in

intensity until woodwind join well over three minutes into the

movement. The central section that follows makes considerable

use of high woodwind. There are also pre-echoes of the third movement

funeral march to come before the sorrowful mood returns. The violin

fades mysteriously into the distance with an accompaniment of

percussion taking us back to the opening material. At no point

in the opening movement do we hear the full orchestra. It is therefore

with considerable effect that Aho unleashes his forces in the

Prestissimo second movement with a vigorous brass dominated

call to arms that plays an important part in the ensuing material.

The orchestra dominate throughout this movement to the point that

the soloist is lost in the cacophony. The violin’s urgent interjections

are gradually overpowered until the opening call to arms returns.

The music grows in brutality until the final bars, which are hammered

out in rhythmic unison. The silencing of the soloist holds for

the entire Lento third movement, which opens and closes

with a sustained unison melody in the violins. The strings are

subsequently joined by the woodwind in a passage where Sibelius

is not too far away. The centre of the movement is essentially

a funeral march, perhaps the closest the symphony comes to Mahler.

The march builds inexorably to a dramatic climax amongst peeling

bells before the music subsides once more into the unison violin

melody with which it opened. Having been pushed aside by the orchestra

during the two central movements the final movement, marked Presto,

once again belongs to the soloist. He has an agile cadenza followed

by an extraordinary passage in which the violin is pitted against

martial percussion. Eventually the soloist is drowned out once

again before the work progresses towards its quiet, consolatory

conclusion.

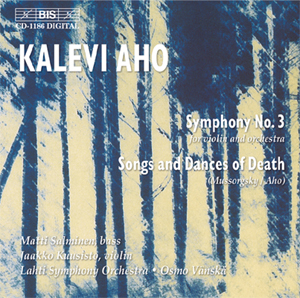

Young Finnish violinist Jaakko Kuusisto is a

more than able soloist in a part that is as demanding as you would

expect of any full blown concerto. The ever growing reputation

of the Lahti Symphony Orchestra under the authoritative direction

of Osmo Vänskä is justified by boldly confident playing

invoking a vivid atmosphere.

Aho’s orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Songs

and Dances of Death came about as the result of a request

for an arrangement suitable for performance by bass and orchestra.

Aho explains that his orchestration was conceived around a "psychological

instrumentation" whereby the specific instrumentation was

decided upon following careful analysis of the poems. The appointment

of instruments is suitably matched to the expressive content of

the words. The orchestration certainly adds drama to the profoundly

pessimistic nature of the poems, not least in the concluding song,

The Field Marshal. The battle scene of the opening possesses

particular presence. Matti Salminen proves a sonorous bass if

not always the most subtly expressive and the orchestra are once

again on fine form.

Overall, this is a disc not to be missed, both

for the undoubted stature of the symphony and the quality of the

recording. The BIS engineers have captured the orchestra and soloists

with an admirably natural sense of space, orchestral perspective

and sonic range. All in all it makes for an edge of the seat experience

and I would be surprised if I hear a better produced orchestral

recording this year. I have already have it earmarked as one of

my discs of 2003.

Christopher Thomas