Readers of classical record reviews often find

it bewildering that the same performance can elicit extremely

wide differences in opinion. I am even surprised when another

reviewerís conclusions are the opposite of mine. Upon reflection,

itís only natural that opinions might greatly diverge. Beyond

basic music structure including the element of contrast, music

is a highly emotional field. It has been with us since the beginning

of humankind because of its impact on our hearts and souls, not

our brains. The best a reviewer can do is point out general preferences

and/or prejudices in order to give readers a fighting chance to

break through the spectrum of personal opinion and make favorable

buying decisions.

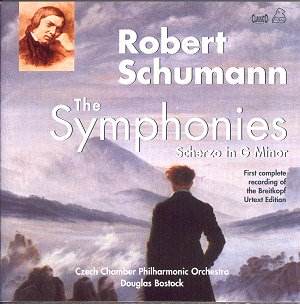

Douglas Bostock, the conductor of this new set

of Schumannís Symphonies, has consistently received a mix of glowing

and disappointing reviews. At one end, he is considered a lumbering

and clumsy conductor who generally employs inadequate orchestras

and dispenses with any meaningful subtlety. At the other end,

he is praised as an electrifying force whose recordings fully

merit space alongside the best interpretations on record.

My review might add to a readerís confusion,

but I hope it will shed a little additional light on Douglas Bostock.

In releasing a set of Schumannís Symphonies, both ClassicO and

Bostock have entered a very highly recorded field. There are literally

hundreds of recorded performances with a staggering number of

them being exceptional.

First, Bostockís Schumann is hardly electrifying.

He does well at conveying the musicís drama and forward momentum,

but thereís nothing in these performances of a thrilling nature.

Also, the volume controls need to be set very high in order for

any sense of excitement to come through. In comparison, the Sawallisch

readings are exciting even at low volume, as he consistently maintains

strong tension.

A second concern is that the sound is on the

diffuse side. Weak definition causes a reduction in tension, and

thatís never a favorable condition in Schumannís Allegros. Thirdly,

versions of Schumannís symphonies such as Sawallischís impart

a strong dignity and stature that Bostockís often rounded attacks

do not allow. This is most noticeable in slow movements, the trios

of the Scherzos, and in the slow introductions to the symphonies

such as the fanfare of the 1st Symphony where Bostock

only offers a small percentage of the nobility flowing through

Sawallischís performances.

To Bostockís credit, I do not notice any lumbering

quality to his interpretations, and the orchestra fullfills its

responsibilities in admirable fashion. Bostock isnít the man to

take full opportunity of nuance and subtlety, but heís hardly

on automatic pilot.

Finally, ClassicO touts its set of the Schumann

Symphonies as being true to Schumannís wishes through use of the

Breitkopf Urtext Edition which is based on Joachim Draheimís critical

new edition that was published between 1993 and 2001. As the liner

notes state, "The recording represents a consistent musical

transposition of this new edition and refuses to make any compromises

with a tradition marred by an overly free and negligent treatment

of Schumannís original indications pertaining to the instrumentation

and tempo".

Such smug statements may sound convincing, but

I detect little difference between Bostockís and Sawallischís

approaches. For better or worse, the new edition does not change

the flavor of the music in the least. Bostock is a little leaner

in texture than Sawallisch, but the difference is not of major

proportions.

In conclusion, the new ClassicO set of Schumannís

Symphonies is rewarding but not among the most compelling accounts

on disc. A diffuse soundstage, lack of definition on Bostockís

part, and a significant deficiency of nobility hamper the performances

to the degree that I cannot recommend the set when better recordings

are available at no more than the mid-price range from Sawallish

on EMI, Kubelik on Deutsche Grammophon, and Szell on Sony.

Don Satz