John Wesley studied at Lincoln College, Oxford

and it was there, with his brother Charles, that he formed the

Holy Club designed to give the like-minded young men a disciplined

regime of holy living. It was that regime which led to the name

Methodism, at first applied satirically. Singing hymns was always

a large part of the Wesley's itinerant evangelism and their first

collection of hymns was published in 1738.

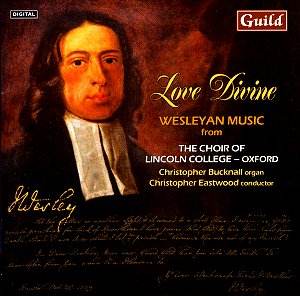

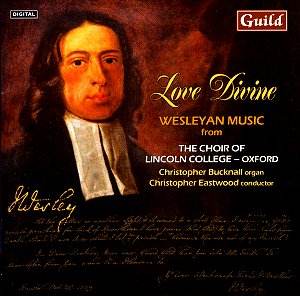

This disc, recorded by the choir of Lincoln College

is designed to celebrate the Wesley's connection to the College.

But the disc is not what it might first appear to be as the choir

sing just six hymns by the Wesleys and it is to Samuel Sebastian

Wesley that the bulk of the programme belongs.

There is just one hymn by John Wesley (a translation

from the German) and five by Charles Wesley. Of these, only one

(Lo! He comes with clouds descending') is sung to the tune that

was associated with it by the Wesleys. All the others have acquired

new tunes subsequently and the choir sing these more familiar

versions. Another hymn, ('Rejoice the Lord is King') was set by

Handel, who was an older contemporary of the Wesleys, but this

setting was not published until Samuel Sebastian Wesley (the grandson

of Charles) published it in the 19th century.

Besides one of his hymns, setting his grandfather's

words, the choir sing six of Samuel Sebastian's anthems. Organist

of Hereford, Exeter, Winchester and Gloucester Cathedrals and

Leeds Parish Church, Samuel Sebastian did much to reform Anglican

church music and introduce contemporary harmony and forms into

the rather stale and old-fashioned Anglican anthem.

This is an attractive programme and it is useful

to have the collection of Samuel Sebastian's anthems. But his

sublimely Anglican anthems rather dilute the Methodist fervour

of Johns and Charles's hymns, a fervour further diluted by using

the traditional tunes rather than ones known to John and Charles.

A case could be made for a programme devoted to the Wesley family,

but then you would surely have to include something by Samuel

Sebastian's father, Samuel Wesley. Samuel Wesley was a child prodigy

(writing his first oratorio at the age of eight). Whilst his music

might not stand extensive revival, a programme devoted to his

father, uncle and son could have fitted in one of his own pieces

and it would have made a far stronger selection. What we are left

with sounds like typical fare from the college services. This

is no bad thing, but the programme had the potential to be something

more memorable.

That said, the choir of Lincoln College make

a wonderfully clean wholesome sound and sound ideal in this music.

A choir with female sopranos and a mixture of female and male

altos, the choir has all the virtues (and the odd problem) that

come with young voices. The upper parts can make an ethereally

pure sound and all voices sing with crispness and liveliness.

But the inner parts can lack definition, there are occasional

moments of untidiness and the extremes of Samuel Sebastian's bass

parts tax the young baritones in the choir.

The choir fields a fine array of soloists, particularly

Silvie Garnsey who contributes a lovely pure, clean treble solo

in Samuel Sebastian's 'Blessed be God the Father'. Where the soloists

act as a semi-chorus, then they sound heavenly. But the soloists

are taxed by the more complex, operatically inspired solo passages

in Samuel Sebastian's anthems. In chapel, on a Sunday evening,

they undoubtedly make a fine impression, but on record the fine

detail and experience is lacking so that these solo passages lack

finesse.

They are not always helped by the conductor,

Christopher Eastwood (for two tracks he and organist Christopher

Bucknall enterprisingly swap roles). He does not have an adequate

feel for the structure of Samuel Sebastian's extensive multi-section

structures. Samuel Sebastian started his working life at the English

Opera House and brought these influences to bear in his early

anthems. Too often, you feel that conductor, choir and soloists,

consider each section as a separate entity and any overall structural

feeling is lost. This may, however, be a fault of the recording

process if the anthems were recorded in sections.

Regarding the hymns, some radical rethinking

was called for. The choir sing them musically enough, varying

between unison and harmony. They would make an inspiring backing

during college services. But listening to these hymns on a CD

player, they all sound terribly slow and not a little dreary.

Rather than perform them in the standard congregational way, choir,

organist and conductor should have remade them anew as small anthems,

suitable for armchair listening. In the hymns, the choir's diction

is adequate, but entirely lacks the feeling for the text and the

fervour that would surely come from the original performances.

Rather than giving us an insight into Charles Wesley's revolutionary

hymnody, these performances resound with comfortable Anglicanism.

Whilst Samuel Sebastian Wesley's anthems remain

popular on anthologies of English choral and cathedral music,

collections of his anthems are rarer. Both the New College collection

on CRD and Worcester College's collection on Hyperion seem to

have been deleted. So if you are interested in a collection of

Samuel Sebastian's anthems, then consider this collection. But

if you are interested in John and Charles Wesley's hymns, then

I suggest that you look elsewhere.

Robert Hugill

see also

review by John Portwood