This year marks fifty since the premature death from

cancer of the British lyric contralto Kathleen Ferrier. Her unique

voice never ceases to impact on the listener; it did so then and

still does now. She was a seminal figure; one of the first examples

of a ‘cross-over’ artist who entertained housewives, factory workers

and royalty in folk music, opera (limited), oratorio, lieder and

the vocal symphonies of Mahler (the latter thanks to Bruno Walter).

In this last respect Walter, and then Ferrier, prepared the way

for Klemperer to continue to establish that composer’s music in

Britain during the 1960s. This has led to Mahler’s huge popularity

today. Ferrier’s career lasted barely ten years from 1942 when she

emerged from her north-western roots where she was first a fine

pianist and then a serious singer from about 1938. As if guided

by a hand of destiny during those ten years, she was passed along

a chain-link fence within the music profession from one figure of

importance to another to progress her career. The list began with

her first teacher Dr Hutchinson, followed by Sargent (who advised

moving to London), agents Ibbs and Tillett, baritone Roy Henderson

(her next teacher), Pears, Britten, Glyndebourne, Festival directors

Rudolf Bing (Edinburgh) and Peter Diamand (Holland), Barbirolli

and Walter.

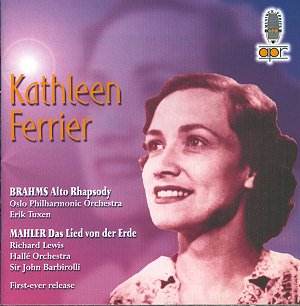

We still await the discovery of the buried treasure

of a recording of Ferrier singing the Angel in Elgar’s Dream

of Gerontius and conducted by Barbirolli. Meanwhile we have

the joys of these two new recordings, known about but not issued

until now, of familiar Ferrier fare. Scandinavia, like Holland,

appreciated Ferrier, and she toured there in 1949 including making

this recording of Brahms Alto Rhapsody (‘Alto Raspberry’

as she called it in her letters) for Norwegian Radio. She had

made a commercial recording for Decca in the expansive acoustics

of Kingsway Hall with the LPO under Clemens Krauss. This was a

disc she was particularly happy with and a work which sat so well

for her. Interestingly Tuxen’s is a swifter performance by three

minutes (than the one with Krauss) but not noticeably so for Ferrier,

who lingers and caresses her golden low register with comfortable

devotion.

The genesis of the recording of the Mahler is

quite extraordinary. On the night of the broadcast (Kathleen Ferrier’s

birthday, 22 April 1952) a young man called Gordon Rowley was

testing out his newly-acquired Ferrograph Mark I tape recorder

at his lodgings in Hertfordshire. In his own words he was literally

‘sticking a couple of wires in the back of my landlady’s antique

wireless set while she was out for the evening and hoping they

did not fall out again before the end. I also had to stop and

start between movements to cut the pauses or it would have overrun

the tape’. True the first seven bars were not recorded, the occasional

beat is missing in the sixth movement and some radio interference

intrudes at times in the last, but for all that this is a priceless

document for which we must offer grateful thanks to Mr Rowley

and to Bryan Crimp for his loving restoration. It is a truly remarkable

document. Its joys lie in the musical collaboration with Barbirolli

(she went on to make the famous Decca recording in Vienna with

Walter less than a month later) but not forgetting the vocal glories

of Richard Lewis in his prime. Barbirolli had conducted Das

Lied von der Erde in 1946 (though not with Ferrier) and did

not start to conduct any Mahler symphonies until a year after

she died in October 1953. However this dream team had given several

performances of the work just prior to making this broadcast.

That he adored the music is clear from the familiar groans and

grunts, as well as much string portamento in the Abschied.

There is also the remarkable playing of the Hallé, which

he had rebuilt during the war years (Janet Craxton is principal

oboe here, Oliver Bannister principal flute before he left Covent

Garden).

As for Ferrier, her diction is amazing with every

word coloured and imbued with emotion, the glorious voice utterly

free of the physical pain with which she was now having to cope.

Her fine performance with Walter may have justly earned its place

in recording history, and also because it is the last extant example

of her singing this work before death claimed her. However this

equally intense and moving account with Barbirolli has just as

much personal love and admiration between them: their shared love

of Mahler’s music, plus the glorious Lewis and the Hallé.

It is a recording for ‘ewig’. What more could one want? Oh yes,

that Dream of Gerontius of course.

Christopher Fifield

(‘Letters & Diaries of Kathleen Ferrier’

: to be published by Boydell & Brewer in October 2003)

|

Error processing SSI file

|