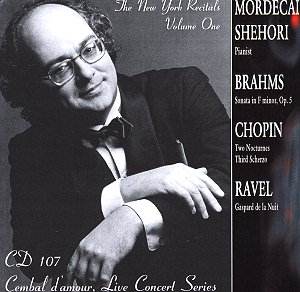

Mordecai Shehori, Israeli-born, studied with the Rumanian

pianist Mindru Katz, whose legacy he has furthered by issuing performances

on Shehori’s own Cembal d’Amour label. Further studies with Beveridge

Webster and Claude Frank followed and Shehori was fortunate enough –

and talented enough – to come into Horowitz’s orbit, experiences about

which he reminisced thoughtfully and perceptively in Harold Schonberg’s

biography of Horowitz. For his recital at the Metropolitan Museum of

Art, which he gave a quarter of a century ago now, in April 1977 he

chose a demanding programme that tested technique and stylistic affinity.

The Brahms Op. 5 Sonata is a big, bold work and receives a commensurately

big, bold performance. In the opening Allegro Maestoso he is powerful

and propulsive from the initial bars and is on splendidly energetic

form. Even in the Andante he is strongly active without any sense of

rhythmic lassitude – he clearly sees this, rightly, as a youthful and

passionate work and makes no attempt to subvert that – and in the poco

piu lento section of the movement he is inwardly reflective but at a

still reasonable tempo. There are oases of romantic repose in the Finale

but Shehori’s playing is strongly forward-looking and takes a long line

in all the movements.

The trio of Chopin pieces make an intelligent grouping.

In the F minor Prelude he is excellent at contrastive playing – the

sense of romantic dreaminess and the urgency of the romantic passion

are all coalesced - and in the succeeding B major we see another side

of Shehori. Here his teasing rubati are joined by the leading voices

of the right hand and a sense of his not playing a proper legato but

preferring instead to concentrate on an intriguing use of rhythmic displacement.

His Scherzo is strong willed and passionate, with his strong, active

rhythmic sense fully engaged. In the difficult conclusion to the piece

he ties the left hand well, creating excitement in profusion and driving

to an overwhelming finish – undeniably dramatic, if perhaps rather too

much so. The recital here ends with Gaspard de la Nuit. Comparison with

so towering a Ravelian as Gieseking is instructive. Shehori isn’t as

even in Ondine as the older man; in Le Gibet Shehori prefers

insistence and intensity whereas Gieseking’s priorities are the pictorialism

of the swaying and of the church bells. Shehori’s Scarbo is certainly

malign and not to be trifled with and noticeably more athletic than

Gieseking’s.

This is a strongly characterised recital by a musician

well versed in matters of text and performance practice. My abiding

impression is of his Brahms, so full of youthful and vigorous action,

so keen to press on to the next thematic view, and so satisfying in

execution.

Jonathan Woolf