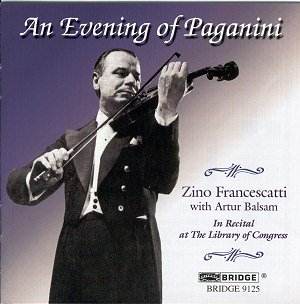

The latest release in Bridge’s archive

material of live concerts from The Library of Congress brings to the

fore Zino Francescatti in a recital dating from 1954. He was teamed

with Artur Balsam, born in 1906, and four years younger than his violinist

partner. Balsam has already made several appearances in this series

as either sonata partner of Nathan Milstein or alongside the Budapest

Quartet. Francescatti was fifty-two and at the height of his fame. Though

he was a contemporary of Heifetz – actually a year younger – Francescatti

has always seemed very much younger and the reason seems to have been

the telescoping of his international career. Heifetz sprang to fame

as a teenager but it took the Frenchman much longer to establish his

career - by which time Heifetz had enjoyed comfortable celebrity for

over two decades. Though Francescatti made recordings in 1921 (last

available on Biddulph) he wasn’t to tour America

until 1939, having previously confined himself to a European career.

It wasn’t until the War’s end that his career really took off.

He had studied with his father,

an Italian violinist who had himself studied

with Camillo Sivori, reputedly Paganini’s only pupil. Francescatti had

a considerable affinity with Paganini and in 1947 recorded eight of

the Caprices for Columbia (Nos 9, 13,

14, 15, 20, 21 and 22) with Balsam in the then fashionably spurious

piano accompanied versions, in arrangements by Mario Pilati. I Palpiti

was committed to disc, again with Balsam, two years later. The Carnival

of Venice variations, similarly with Balsam, were recorded in April

1954 in a limited edition for Columbia (PE 19) though

I’m not sure how much publicity this received. Unusually Bridge doesn’t

date this Library of Congress recital – all of their other recitals

are precisely dated – but it must have been quite near the Columbia recording

date, which was April 30th 1954. As

for the Concerto, Francescatti’s recording with the Philadelphia and Ormandy

was a much-admired traversal, dating from January 1950 (sleeve-note

writer Eric Wen in his otherwise excellent notes is mistaken in ascribing

the accompaniment to Mitropoulos and the New York Philharmonic).

The recital highlights all Francescatti’s

greatest qualities; technically magnificent, tonally expressive, lyric

and with exceptional elegance. He possessed a very fast vibrato and

one - as has been often noted – of some considerable oscillation (though

not at all analogous to, say, Ruggiero Ricci’s or to the older generation

of French violinists whose employment of finger tip vibrato led to nanny

goat tonal production. Renée Chemet, born only fourteen years before

Francescatti, is the most obvious example). So whilst this recital is

ancillary to Francescatti’s commercial discography it is still tremendously

exciting to hear the piano-accompanied Concerto and the 17th

Caprice (otherwise unrecorded by him). He starts the Concerto a little

slowly but we can hear some fabulous electric trills, harmonics superbly

in tune – Francescatti’s intonation was invariably dead centre – and

his unflappable concentration in the face of an off-stage crash. His

fast vibrato is powerfully suited to the work and his flying staccatos

are thrown off with devilish precision. He is elegant in the Carnival

of Venice but also full of flair and drive. The pizzicati episode might

turn many a violinist green with envy, even now. The Caprices differ

from the commercially recognised performances inasmuch as Francescatti

uses his own arrangements for Nos. 13, 17 and 24 – and these are all

ringing and characterful performances, bringing out the lyric possibilities

of the individual pieces. No. 15 is especially successful in its terpsichorean

panache and he drives No. 21, the A major, to a drama fuelled conclusion.

His bowing in No. 9 is remarkable and the only slight disappointment

his own rather pat ending to No. 24. I Palpiti is similarly negotiated with the utmost in lyric panache. As

ever with Francescatti, beauty of tone is never lost, no matter how

perilous the demands placed upon him.

Fiddle fanciers won’t hesitate;

those who know Francescatti’s Concerto with Ormandy may not have the

1947 Caprices. But there isn’t a huge amount of live Francescatti around

and as far as I’m concerned you can never have too much of a good thing.

Jonathan Woolf