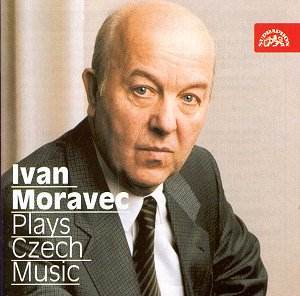

There has been a welcome resurgence of interest in

the art of Ivan Moravec of late. One of Philips’ ‘Great Pianists of

the Century’, this and other more recent releases have brought his pianism

to the attention of those perhaps only imperfectly aware that he is

one of the master pianists of our age. This Supraphon CD of material

taped in 1962 and 1984 was released in 2000, the year of Moravec’s seventieth

birthday. The following year I saw him in the Queen Elizabeth Hall,

playing Chopin in a recital of characteristic modesty and unspectacular

greatness. He stands now with Jan Herman and Rudolf Firkusny in the

triumvirate of the greatest Czech pianists to have recorded and this

disc gives yet more evidence of his colouristic sensitivity, tonal beauty

and musical buoyancy.

The Smetana A Minor Polka is played with lilting affection

and with a flexibility of rubato that never slides into the flaccid.

The piece has a simple but not simplistic melodic appeal and Moravec

can either glitteringly harden his tone when necessary or bathe passages

in half-lights of almost spectral beauty. He catches the delicacy and

the dreaminess of Hulan (The Lancer) from the 1879 Czech Dances

laced as it is with something of the nostalgia of Schumann. The variations

are in Moravec’s hands decorative flecks in the right hand whilst the

lift is strong and even, dynamically gradient and noble. Obkrocak

is convulsively exuberant and the Furiant if anything even more dramatically

successful a conception. At 1’30 Moravec leans on the right hand passages

slightly; the effect is one of infinite rhythmic elasticity far removed

from mannerism. He is capable of tremendous depth of unforced tone –

never hardening or becoming brittle and as here the effect is one of

drama and excitement. He infuses the G Minor Polka with an appropriate

sense of theatricality and a secure sense of rubato whilst Memories

of Plzen, one of the weaker pieces, is still prettily insistent.

When he turns to Suk he does so with acute sensitivity. His O Matince

displays a wealth of characteristic virtues. He is not over inclined

to linger – he is significantly fleeter and less dreamy than Slovak

pianist Marian Lapsansky on a rival disc for example. In the first of

the cycle of five he eschews sentimentality and promotes instead a simple

gravity of utterance; the adagio has a surging, verdant freshness to

it, its slight air of melancholy subsumed into the patina of Moravec’s

lyricism. The uniform depth of his bass in the third, How Mother

sang at night to the sick child, is a subtly ominous foreshadowing

of the next, Mother’s Heart. Moravec never draws attention to

the programmatic nature – or at least to the descriptive nature of the

movement’s titles – but instead lets the music grow from within;

in the last piece, Remembrance, he is by turns, and wholly sensitively,

agitated, sonorous, veiled and regretful.

He plays the Humoresque with requisite flourish – it’s

an immature, rather fin de siècle piece whereas Pisen lasky

is also one of Suk’s early works and one of his most famous. Moravec

stabs away at the insistent bass notes that run throughout, tying the

work securely to something rather more than mere effulgent ardour. His

rubato is at the service of the work’s moods, his tone unselfconsciously

ravishing. Korte’s Sonata was composed between 1951-53 and a prizewinner

at the Bolzano Competition. Opening in stentorian fashion a neo-baroque

passage intervenes which itself relaxes into a romanticised episode

that winds down before a return to the opening brittle flourish. Elements

of conjunction and opposition pervade the second of the two movements

– strident neo-baroque once again but here undergoing a process of translation.

The triumphant baroque theme resurfaces once more in an intriguing procedural

development; this makes the work sound far more mannered and artificial

than it actually is and Moravec’s advocacy speaks of his own admiration.

All but O Matince derive from a live

recording at the Dvořák Hall of the Rudolfinum in 1984; the audience

is commendably silent, except for occasional applause, though Moravec’s

guttural commentary, a kind of wounded yelp, is also audible at one

or two moments. The disc has been beautifully transferred and

enshrines yet more testimony to Moravec’s exalted status amongst contemporary

musicians.

Jonathan Woolf