This is the third and final volume in Tahra’s celebratory

series that takes Jochum’s 1902 year of birth as a welcome pretext for

twelve CDs packaged with distinction in black and white/sepia tinted

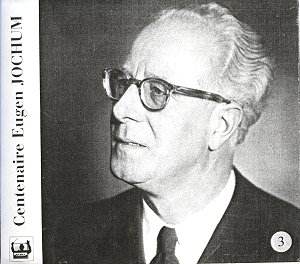

boxes. The Three Ages of Jochum in fact, for each box sports a photograph

of the conductor, left facing for reasons of conformity, another thoughtful

Tahra touch – the curled and wiry haired, quietly smiling and bespectacled

youth of Volume One leads on to the silver haired, quiet gaze of the

middle aged man and the august and benign strength of the elderly Jochum,

his dramatic Roman nose obscured by the omnipresent glasses.

What is the least likely repertoire one can think of

when it comes to Jochum? Coleridge-Taylor maybe or Mascagni? For all

his benign appearance one doesn’t much associate him with frivolity

or lollipops. And so, no Coleridge-Taylor and no Mascagni of course

but leafing through the repertoire listing which is included in volume

three – the first volume includes a biography and the second a discography

– is a most intriguing experience. So at random here are some surprises

– at least to me – amongst his repertoire;

Fricker’s First Symphony, Glazunov’s Violin Concerto, Honegger’s Fourth

Symphony (though he was an avid performer of the Fifth), Janáček’s

Glagolitic Mass, Kletzki’s Violin Concerto, Krenek’s Johnny spielt auf,

Lassus, Malipiero’s Cello Concerto,

a lot of Frank Martin, Martinů’s Concerto for two pianos and Concerto

grosso, Roussel’s Fourth Symphony, Sibelius’ Seventh and Violin Concerto,

Tippett’s Ritual Dances, Vaughan William’s Tallis Fantasia; and too

many Dutch works to mention, not at all surprising given his

close association with the Concertgebouw. The final volume however is

both a consolidation of expected verities and a welcome exploration

of the Franco-Belgian repertoire that again is not much part of Jochum’s

discographic inheritance; Debussy, Berlioz and Franck.

There’s plenty of clarity and purpose in his Debussy

and if the 1963 sound is a little cramped it doesn’t do too much damage.

I liked Sirènes for its boldness and for the singing of the women

of the Toonkunstkoor choir that, although rather recessed and indistinct,

still manages to register strongly. Benvenuto receives an affectionate

and occasionally quite brash reading – Jochum first began conducting

it in 1935 and along with Romeo and Juliet was the only Berlioz in his

repertoire. With Wagner we are on known territory. The Good Friday Music

(Concertgebouw, 1972, live – as are all these performances in this last

volume with the exception of the Berlin Schubert) is splendidly eloquent

and nuanced whilst the overture to the Mastersingers is resilient, strong

and firmly handled. Elly Ameling joins the Concertgebouw for Bach’s

Wedding Cantata, taped in 1973. With her are Hermann Krebbers and oboist

Cees van der Kraan as well as an unnamed harpsichordist. Ameling had

an almost perfect voice for Bach, pure yet vibrant, well supported at

the bottom and yet capable of secure extension at the top. Here she

steals in with exquisitely controlled breathing almost before one has

noticed her. The coffee house intimacy of the Cantata is reinforced

by the refinement and appositeness of the accompanying instrumentalists

– a small band – and by the soloists, principally Kraan (excellent)

and Krebbers (delightful). Ameling’s affectionate phrasing and winning

way with words and mood register even more strongly as the cantata develops

– this is a well paced and durable performance. When it comes to César

Franck one finds Jochum relishing the Wagnerian moments as well as some

beautifully veiled string tone. The rise and fall of his phrasing is

charted with determination though his overall conception is certainly

not over fast. It’s a strong, good but not outstanding performance.

Brahms’ Fourth Symphony opens with a slow but intensely

elastic sense of sculpted movement; wind detail is very much to the

fore in the opening Allegro as well as some splendidly subjective phrasing.

I don’t suppose anyone has vested the Andante with as much unstoppable

and emotion laden hysteria as Knappertsbusch in concert in Cologne in

1957. Jochum is of course far more decorous, seeing to sectional discipline

even within a chastely emotive patina, bringing sophisticated technique

and purposeful individuality. And how well he encourages some diaphanously

draped flutes in the Allegretto – truly delightful – and negotiates

some powerful ritardandos in the finale where strong weight of tone

reinforces the sense of the strain that Jochum seeks to convey. His

first violin entries are clearly audible here and not covered by the

brass as they sometimes can be and he balances sections with great acuity,

as one would expect. Something has gone wrong with the timing and tracking

here though; the Allegretto lasts six minutes not twelve and the tracking

of the finale doesn’t start until half way through the movement. The

Grieg Concerto teams Emil Gilels with Jochum and his "second"

orchestra once more, the Concertgebouw. This is a strongly characterised

reading and very communicative, Jochum shaping feminine woodwind responses

to Gilels’s masculine passagework. The pianist takes care though to

shape his phrases with requisite finesse and both men seem in one accord

in the Adagio, which is full of poetic spirit, and in the bracing and

increasingly driven finale. The final and most recent performance is

of the Schubert, the Great, in a May 1986 performance with the

RIAS Orchestra of Berlin. Strong and songful in the first movement Jochum

is occasionally gaunt and resolute in the Adagio. He is also very slow

here but despite this it is no valedictory reading, no autumnal leave

taking. On the contrary it’s a frequently candid, considered, well-paced

and thoughtful traversal, flecked with moments of disruptive splendour.

There is much distinguished music making in this and

in the two other Jochum sets that form this centenary tribute. As I

wrote in my introduction to Volume I this now must stand as a cornerstone

edition for those interested in the broad sweep of Jochum’s discography.

Presentation is impressive, documentation thorough and intriguing in

equal measure and the whole edition a conspicuously fine example of

thoughtful intelligence applied to a most worthy object of homage.

Jonathan Woolf

Volume 1 Volume2