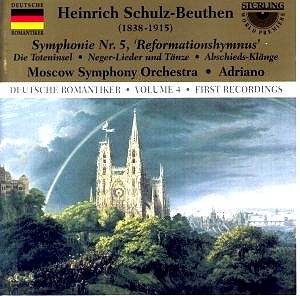

This adventurous album is released in Sterling’s ‘Deutsche

Romantiker’ series and, once again, we have Adriano to thank for unearthing

more interesting Late Romantic gems. As he says in his erudite notes

(for this album he also edited the manuscript of the main work, Schulz-Beuthen’s

‘Reformation Symphony’), the works of Brahms, Bruckner, Mahler and Richard

Strauss have tended to overshadow so much other Late Romantic German

music of which the work of Heinrich Schulz-Beuthen is just one example.

Schulz-Beuthen’s Symphony No. 5 (The Reformation Symphony)

is, as Rob Barnett has pointed out in his review of this recording also

on this site, is based on Martin Luther’s 1529 hymn, Ein fest burg

ist unser Gott. Schulz-Beuthen may well have had Luther’s 400th

anniversary in mind when he composed this 18+ minute work. The opening

movement opens powerfully and proceeds in pomp and swagger with chivalric

motifs and grand flourishes for music that Elgar would have marked nobilmente.

Indeed there is a little to remind one of Elgar here; but there

is, alas, just that bit of banality too that reminds this reviewer of

music for the silent cinema. The second more successful movement begins

with the organ, cello and later woodwinds in a quieter lyrical mood,

intoning a theme, the beauty of which develops with each repetition.

This theme alternates with louder, dignified, stately ecclesiastical

material. The third movement returns to the swagger of the first movement

with fanfares blazing. The finale builds on this mood so that the work

ends after a solemn processional, and serener solo religioso

material for the organ, in a huge climax like that of Saint-Saëns

Organ Symphony. Although this symphony can in no way rival that work

or Alexander Guilmant’s Symphony No. 1 for Organ and Orchestra, it has

to be an action adventure film director’s dream.

The most satisfying work in this programme is Die

Toteninsel (The Isle of the Dead) composed in 1909. It is every

bit as dramatic and effective as Rachmaninov’s more famous composition

and Max Reger’s version within his Böcklin Suite. [Böcklin

seems to have been very preoccupied with this subject for he painted

this gloomy but powerfully evocative scene in five different versions

between 1880 and 1886]. The power of the opening with darkly commanding

throaty brass has great impact and creates a brooding, funereal atmosphere.

This material on each of its successive return carries more than a hint

of menace and there is a very atmospheric and convincing evocation of

the little boat sailing over deep and turbulent waters towards the mysterious

island with its towering mausoleum cliffs and cypress trees. But Schulz-Beuthen

also has a luscious romantic theme for his lyrical interludes suggesting

the loves and serener domestic life of the deceased and the expressive

cello solo in the centre of the tone poem hints at some personal tragedy

or loss.

The Negro Songs and Dances are charming and

unpretentious melodious little pieces that may have originated in the

U.S.A. but sound equally middle-European in Schulz-Beuthen’s adaptations.

The best-known piece is the well-known song Oh Susannah! - given

a nicely sentimental, nostalgic air here. The opening Allegro animato

trips and trots along genially with plenty of exercise for the triangle

which returns upstage in the merry dance that is the fourth Allegro

movement. The second piece, Moderato assai is a bitter sweet

salon confection that yearns and sighs - and it might well have been

penned by Brahms. Tambourine is to the fore with brass interjections

in the Allegretto con spirito, gaio assai. This is followed by

the coy sad little Moderato, molto malinconico. In higher spirits

comes an Allegretto scherzando, a rustic dance that bubbles and

laughs its way along. An Andantino doloroso brings back the clouds

but the piece ends in determined optimism (Solenne e maestoso: Andante)

with fanfares dominating over cosy nostalgia.

The equally charming Sounds of Farewell is a

little suite for strings that seems to carry over the character and

atmosphere of the Negro Songs and Dances into its vivacious opening

movement, there are those lively trotting rhythms and the nostalgic

cosiness again. The second movement is a lovely sweeping, yearningly

romantic melody that had me thinking of Elgar’s Serenade for Strings.

The Allegretto moderato, third movement trips along prettily

and then proudly shrugs in its centre. The fourth piece is quieter and

autumnally reflective.

Once again Adriano has unearthed some appealing music

that deserves to be more widely known – particularly Schulz-Beuthen’s

version of The Isle of the Dead. This may not be the cream of

Late Romantic German music but it could lay claim to being near ‘the

top of the milk’.

Ian Lace

See also Review

by Rob Barnett