Although in reality very brief, Handelís time in Italy

(1706-1710) represents one of his most productive periods. During this

tenure, Handel frequently returned to Rome, which is a mystery to many

musicologists, as he would have had no opportunity to perform or compose

opera there, the genre being banned at the time in that city. His sixty

or so Italian cantatas were written primarily for private Roman audiences.

Scholars debate as to whether or not the cantatas were a harbinger of

Handelís operatic style. Evidence toward this conclusion lies in the

composerís life-long habit of borrowing from earlier works. Much of

the material found in the cantatas turns up in later operas. On the

other hand, some cite the frequent use of chromatic melodies, contrapuntal

settings and other gestures intended to point up subtleties in the texts

as evidence of the stylistic originality of these pieces.

The keyboard suite presented here dates from 1720,

and is a response to the unauthorized publication of some of his other

harpsichord works. That the rhythmic hammering of a blacksmith inspired

the fourth movement air and variations is a legend of nineteenth century

invention. Originally attributed to Johann Sigismund Weiss (c.1690-1737),

the authenticity of the Sonata in D for flute and continuo was proven

by Handelís own self-borrowing habit. Themes from this sonata exist

in two earlier works, composed before Handel and Weiss actually met.

The air from Water Music is a transcription of Handelís own making.

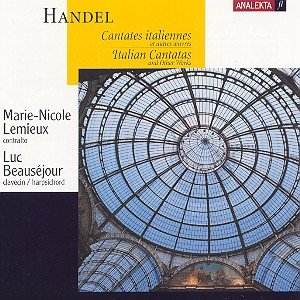

The star of this excellent recital is contralto Marie-Nicole

Lemieux. Recently the winner of a number of prestigious competitions,

this singer from Quebec is starting to enjoy a wide-ranging international

career. Hers is the rich, warm contralto of the Maureen Forrester tradition,

a rare thing indeed these days. She approaches baroque music with a

full throated sound, and shies away from the "early music"

affects that clutter a great deal of current performances. She leaps

into these melodramatic texts and portrays them with intense passion,

thus granting some credibility to what could otherwise be deemed as

eighteenth century soap opera material. One is only disappointed in

her singing when she attempts coloratura. While her legato singing is

glorious, the roulades in the faster passages simply are not clean enough

to be satisfying. They sound a bit too labored and I found myself working

with her to get through them instead of marveling at their execution.

Perhaps a little less of the Forrester approach here and a bit more

of Marilyn Horneís legendary passagework would improve matters.

Luc Beauséjour is not only a fine accompanist,

but his solo playing is one of the high points of this recital. He plays

with a grace and elegance that is delightful to hear. Although his virtuosity

is apparent, he never shoves it to the foreground. Instead he lets the

music speak for itself, rollicking along with it when appropriate, singing

into it in the more lyrical moments. He shines in whatever role he is

playing on this disc. Marie-Céline Labbéís flute playing

is stylish and elegant, although I might have wanted for a little less

decay at the ends of some phrases. She produces a lovely tone. Amanda

Keesmaat is a solid continuo cellist, giving exactly what is needed

to the ensemble.

Analektaís engineers have done splendid work. I was

particularly pleased that the harpsichord was recorded in a natural

ambience, not over amplified. Face it; the harpsichord is a light delicate

instrument that was more at home in salons than concert halls. Nothing

is more annoying than hearing this instrument with a microphone shoved

down its throat. Balances are perfect and this is one enjoyable listen.

Last but not least, this is one of the best program

booklets to come across my desk in some time. The notes are excellent,

we are provided with full translations and the cover art is beautiful.

Other labels should take note: this is how it is supposed to be done!

Kevin Sutton