Though the public has always preferred the Préludes

to the Etudes – a fair number of the composer’s best known pieces are

to be found in the first book of the former – I wonder if Fou Ts’ong

feels especially drawn to the Etudes. He responds vividly and precisely

to their wayward humour, their love of strange note-patterns and their

wry, acerbic harmonies. He does not attempt misty, half-heard sonorities,

but his sound retains a glistening quality which compels the attention.

And I think it is to this side of the Préludes

that he responds in particular. He is unfailingly effective in the humoristic

ones such as La sérénade interrompue, Minstrels

or Général Lavine; and in Hommage à S.

Pickwick he scores a success with what is generally considered to

be one of Debussy’s weaker pieces. Equally fine are those which call

for élan or joi de vivre – Les Collines d’Anacapri

and La Danse de Puck, for example. He is not afraid to play

out when the marking is mezzo forte or forte and, while his pedalling

is very subtle, he also keeps many passages clean – try the opening

of Feux d’Artifice – which are often covered in a haze of pedal.

He can sometimes seem to lack the subtle half-lights – his fairies in

Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses are a surprisingly

riotous lot, in contrast to the sensitive and poetic, even if robust,

treatment of Ondine. He creates an exquisitely beautiful atmosphere

in Des pas sur la neige, and produces some ravishingly poetical

atmospheres in the later stages of La terrasse des audiences,

making his slightly arid and over-present treatment of the opening pages

the more puzzling. One appreciates that he does not want to sentimentalise

La fille aux cheveux de lin, but here and in Bruyères

he verges on the uncaring.

These twenty-four Préludes cover a wide poetic

spectrum and many famous recordings of them have been made. Probably

no single version is going to provide the unanswerably definitive solution

to each piece, or even one listener’s favourite interpretation of each

single one. It is likely that any version will have a few disappointments

along the way. I shall never throw away my Gieseking, and those few

left us by Guido Agosti should be heard. But Fou Ts’ong now joins the

elect and whenever I am considering Debussy interpretation his will

be among the versions I shall want to hear. It is particularly recommended

if you want your Debussy fairly up-front and hedonistic (but sometimes

also mischievous); maybe a little less so if your preference is for

something more intangible. The very fine recording is a further attraction.

I quote Peter Charleton’s note about Feuilles mortes and leave

you to decide whether this sort of thing (there is one for every Prélude)

will increase the value of the package.

A terrible portrayal of despair, the poet’s mind

seeing in "Dead Leaves" a life sunk into a brittle shell tossed

and scuttling on the sodden ground. A quickened pace bestirs us from

self-contemplation. A shaft of light penetrates but then it fades. The

leaves are again noticed but somehow they are now different.

But to give Charleton his due, his generalised introductory

comments to both the Préludes and the Etudes are helpful. A little

more care over the booklet production would not have come amiss. Debussy’s

middle name appears as "Achile" and the date of his death,

correctly given on the cover, is anticipated to 1917 in the notes.

Christopher Howell

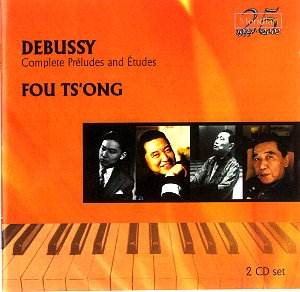

![]() Fou Ts’ong (pianoforte)

Fou Ts’ong (pianoforte)

![]() MERIDIAN CDE 84483/4-2

[2 CDs: 66’15"+70’56"]

MERIDIAN CDE 84483/4-2

[2 CDs: 66’15"+70’56"]