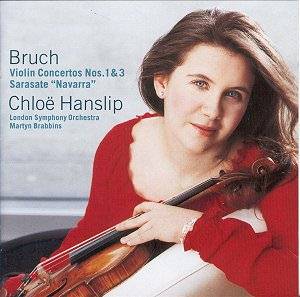

There is no doubt about the talent of

the young violinist Chloë Hanslip. Strip away the hype (not helped by

some appalling booklet photographs, including one in a Toulouse-Lautrec-like

pose on the ‘wobbly’ Millennium Bridge in London in which she appears

to be freezing cold) and the rest is admirable, and I lauded her first CD fairly

unequivocally. That she is technically up to the task is in no doubt,

on the other hand her emotional level is currently fired by the freshness

of youth matched by enthusiasm and love of the music she plays, and

Bruch’s first concerto is clearly one such work. True, she over-indulges

here and there, the pauses and some of the slowing downs she inserts

are excessive, but the finale catches fire and she more than rises to

its challenges. Brabbins and the LSO provide matching accompaniments

(what Hanslip, inevitably for her age, lacks in angst, the orchestral

sound more than compensates for) and just about keep up when, coming

down the final straight, Hanslip puts her foot down hard on the accelerator

pedal and rushes to the finishing line. She tackles the third concerto

head-on, technically far harder than the first, a brave choice and an

excellent performance too, full of muscle in the outer Allegros and

lyrically sensitive in the Adagio, though occasional misjudgements of

intonation in wide leaps from one end of her borrowed Guaneri del Gesu

to the other are hopefully not going to develop into bad habits.

There’s a nice concluding filler with

her partner from her Brit Awards appearance, Mikhail Ovrutsky, in the

unusual Navarra by the Spanish virtuoso Sarasate (who worked

closely with Bruch on more than one occasion), performed by both of

them with plenty of stylish Spanish flavour and technical panache, guitar-imitations

and all. All ‘too silly’ as the Major used to say when interrupting

Monty Python sketches, but great fun nonetheless.

Julian Haycock’s booklet notes no doubt

made full use of my biography, to which I have no objection whatsoever,

though it’s a pity that in so doing, he did not correct my original

error in mathematics when I described Bruch’s wife Clara as sixteen

years old when he married her in 1880, when she was in fact ten years

older than that (born in 1854). Other factual errors also need correction.

Max stayed with her till the end of her days, not the other way around

for she predeceased him by a year, and it was Cambridge, not Oxford,

which awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in 1893. Neither do I recall

that the first violin concerto ‘thrilled the first night, creating a

sensation’. Apart from Bruch quoting from Joachim’s letter to the composer

that it had ‘a resounding success’, therefore we are relying on double

hearsay, we have no reports of that performance. As to Ferdinand David

(hardly ‘elderly’ at 58), described as ‘was allowed to put his oar in’

with a performance, it somehow sits ill as a version of the events.

By the way, not all the photos are bad and some bear an uncanny resemblance

to Tasmin Little - no bad comparison there either.

Christopher Fifield