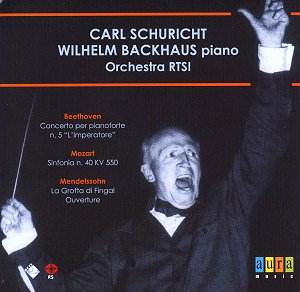

Carl Schuricht was eighty-one when he gave this concert

at the Kursaal Teatro Apollo in Lugano in April 1961. The Emperor

joins the small list of other surviving Beethoven accompanied performances

– Kempff in 1955 in the First and Arrau in 1959 in the Third – both

made with the Orchestre National de France. The Swiss Italian radio

broadcast captures the concert in very acceptable sound; little recession

or over prominence really mars the enjoyment. The Emperor is

by no means note perfect but it captures Backhaus and Schuricht in notably

grand and animated form. The latter encourages eloquent flute and oboe

contributions in the first movement with Backhaus taking on a strata

of chamber intimacy often glossed by more gimlet-eyed performers. There’s

no doubting his chordal power, however, when he chooses to unleash it.

Yes there are fluffs and finger slips in the second movement but this

is unusually alert and strong playing, with no oases of relaxation;

some may think it rather hard-nosed and impassive but others will appreciate

its relative tensile strength and also its refusal decoratively to linger.

This is a performance, for all its digital imperfections and relative

inflexibility, that knows precisely where it’s going. Venomous attacks

accompany Backhaus in the finale along with more dropped notes, an almost

inevitable corollary of concert making; again this is distinctive, frequently

distinguished, often granitic music making, the two men making a remarkable

alliance (the pianist, at seventy-seven was the conductor’s junior by

only four years).

Presumably Aura has reversed the running order of the

concert, beginning as they do with the Concerto and ending it with the

Hebrides Overture. The Mozart would have ended it and this receives

a most persuasive and distinguished reading. Schuricht elicits some

fine first violin playing in the opening movement – something that Hermann

Scherchen could not always manage to do from the same orchestra. In

the Andante one can hear the layering of string tone, a degree of heightened

expressivity and a sense of evolutionary momentum without undue haste

– all very impressive. His minuet is strong and rock solid and the finale,

with some individual touches of rubato, generally convincing. In fact

this is, in almost all respects, a consistently excellent performance

and one that is informed by imagination, technique, experience and an

acute ear. The Hebrides plays us out, with Schuricht’s crescendos timed

to perfection. In fact the whole disc shows him as a conductor of vastly

elevated talent.

Jonathan Woolf