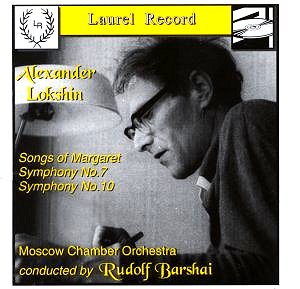

Rudolf Barshai has a special and mutually beneficent

relationship with Herschel Burke Gillbert's Laurel Record company. Barshai

collectors need to search out not only Barshai's Melodiya and EMI Classics

discs but also Laurel's Brahms symphonies (2 and 4) and his Mozart and

Rachmaninov.

It was Barshai who formed the Moscow Chamber Orchestra

and with them premiered Lokshin's Symphonies, 4, 5, 7, 9 and 10 as well

as the Songs of Margaret. Tragically Lokshin, who never trimmed

his sail to match the Soviet westerlies, died virtually forgotten in

his native USSR.

The Songs of Margaret are related to

the Trois Scènes du Faust de Goethe on BIS-CD-1156, a

work of 37 minutes duration by comparison with the 18 minutes of the

Songs of Margaret. It is written in a caustically romantic style

which I link with a work such as Nicholas Maw's Scenes and Arias.

Imagine a series of five 'mad scenes'. This is Puccini filtered through

Berg and through Shostakovich. There you have a broad approximation

of the style. The singer is called on to vault the skies more than once

(e.g. tr.4 1.09) and this she does consummately. It would have been

far too easy to portray Goethe's Margaret as inhumanly demented but

Lokshin's power also conveys compassion; indeed the cycle ends with

an overpowering sense of tender resolve.

The orchestra sounds bigger and bolder that the chamber

orchestra ‘tag’ lead me to believe and the Kharkiv-born soprano Ludmilla

Sokolenko meets every one of the volcanic challenges of the score with

power and emotional commitment. She has a grand operatic voice captured

unshrinkingly by the Melodiya engineers.

The 1970s must have been a time of giddy cornucopiac

activity for Lokshin. These two symphonies fall, temporally, either

side of the Margaret Songs. The Seventh Symphony is memorable

for its liquid horn solos, unmistakably old-time Russian in the introduction

(tr.8) and in Minamoto Saneaki (tr 12). The trumpet is just as

Slavonically blatant. Though normally sure-footed the engineers just

occasionally miscalculate. Was it really necessary, in The road is

paved with flowers for the engineers to pull back on the recording

levels. The music brilliantly captures the steady descent of the thermometer

towards the chilly end of mortality.

Three years and three symphonies onwards comes the

Tenth Symphony which embraces the words of one poet rather than

the Britten and Shostakovich anthology habit. The Tenth charts a mood

trajectory similar to that of the Seventh curving from a perspective

in which warmth is cooled by thoughts of death to autumn and wintry

bereavement; typically Russian.

The recording quality is cavernous. I note that these

recordings were in the studio within two to five years of the completion

of the compositions.

The words of the three works are printed in translation

in the 28 page insert booklet. They are given in English translations

by Walter Barshai. The sung words (Russian … as you would expect) are

not printed. I rather missed them and certainly it would have been good

to have them in transliteration; indeed this is preferable to giving

the words in Cyrillic (as happened with the recent Chandos set of Prokofiev's

The Story of a Real Man) which is likely to be of little direct

value to English monoglots wanting to follow the contours of the sung

words.

The booklet essays are well written and admirably preoccupied

with facts. The use of a bold font throughout is a minor distraction.

Powerfully intense traversals of a fascination with

death and bereavement. Typically Russian.

Rob Barnett