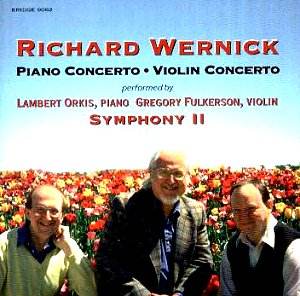

Richard Wernick was a pupil of a number of distinguished

talents – Ernst Toch, Aaron Copland and Boris Blacher amongst them.

He was himself a teacher for nearly thirty years at the University of

Chicago; not that there is anything remotely academic or didactic about

these two strongly characterised and powerfully argued concertos. As

Bernard Jacobson’s notes judiciously aver Wernick’s music fuses technical

expertise and a highly personalised use of tonal and near tonal elements.

Structurally individual as well, Wernick’s concertos resist confident

critical judgement. He belongs to no convenient "school" and

his often rough hewn and angular music is full of the most impressive

sonorities and conjunctions.

The Piano Concerto was composed between 1989

and 1990, commissioned by the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington

and Mstislav Rostropovich – and it was premiered by them and by Lambert

Orkis in February 1991. A complex fantasia first movement ("Tintinnabula

Academiae Musicae") opens with some viciously saturnine trombones

contrasted with the solo piano’s almost pointillist displacements before

some resolute and decisive rhythmic attacks. By some way the longest

of the three movements it gathers itself in intensity and complexity

and by the time of its final peroration the orchestra has grown impressively

stentorian, with brass dominant, percussion strong and the piano taking

an ever more expansive role. The slow movement is static, rather romantic,

with Mahlerian hints, bedecked with some rather keeningly expressive

orchestral solos. The middle section however, in utter contrast, is

fractious and active, insinuating with percussive drive before a sense

of dappled calm returns, flecked and rapturous and yearning. The brisk

finale ("Réjouissance") is ebullient, with virtuoso

percussion and driving, unstoppable culminatory spirit.

The Violin Concerto was written a few years

earlier, in 1984, and was premiered in 1986 by Gregory Fulkerson with

the Philadelphia Orchestra and Riccardo Muti. Wernick, something of

a master of oppositional trajectory, sets up nervous energy in profusion

in the first movement – in which the edgy solo violin is contrasted

with the assured orchestral responses. The massed orchestra is more

powerful, slow moving and less nimble than the protagonist who, finally,

at the short movement’s conclusion has the last, decisive word. In the

slow movement – the longest at over twelve minutes – Wernick explores

incremental changes of texture and tempo, discovering moments of almost

spectral intensity, assailed, but never consumed, by the orchestra’s

jabbing, baleful brass. The finale follows immediately from the involved

complexity of the slow movement. It’s tough, pungent, rhythmically exultant

but attempting to resolve thematic material previously left unresolved.

It is intriguing that the full-scale cadenza toward the end of the work

is not at all experimental but firmly in "The Tradition".

It seems in some oblique way to recognise some hierarchical place in

the syntax of the concerto form in which to explore thematic material.

And it does so in a confirmatory and affirmatory way, drawing together

strands that lead satisfactorily to the conclusion of the work.

Wernick uses dissonant counterpoint; his rhythms are

dramatic and driving; his orchestration is colourful, his lineage eclectic,

his gift for oppositions, for characterisation strong. These are tough

works in many ways and I wouldn’t want to pretend otherwise, but they

are creatively tough and journey with intense drama and feeling.

Jonathan Woolf