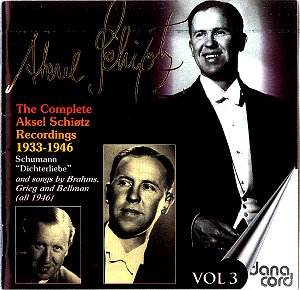

Once again I refer readers to my

review of Vol. 1 of this series for brief biographical notes on

Aksel Schiøtz. Vol. 3 completes the series of recordings he made

in London immediately after the war, accompanied by Gerald Moore and

produced by Walter Legge.

Although only a few months had passed since the recording

of Die schöne Müllerin, the voice has greater presence

and the piano sound more bloom. It is really remarkably good for its

age. The sheer luminous beauty and loving care of Moore’s playing would

be an inspiration to any singer. Schiøtz impresses, as ever,

for the ease of his delivery, the words and the vocal line apparently

at one, and for the musicality of his phrasing. Ich grolle nicht

is not rushed off its feet and there is everywhere the impression

that the deepest consideration has been transformed into the purest

feeling. I realise these are generalised words; it is so much easier

to give chapter and verse when things are wrong. However, a previously

unpublished version of this cycle with Folmer Jensen dating from 1942

is included in Vol. 8 so I hope to have the chance to make closer comparisons

in due course, and perhaps to gain some inkling as to why this

version seems so perfect.

The booklet prints Schiøtz’s own notes on performing

the cycle, written in 1970. At times this sort of thing can be embarrassing

– so many performers write one thing and do another. But Schiøtz

practices what he preaches, and so his notes make an illuminating supplement

to the performance itself. When the world is rather full of singers

who think that a song really begins when they start singing and

finishes with their last note, let us hear what Schiøtz

has to say about the postlude: "The beautiful and expressive piano

postlude recalls the mood of previous songs. It encompasses all the

misery and poetic love of Dichterliebe. The singer should try

to relive all the emotions he has been trying to express in these sixteen

gems of song, and he should stand still while he listens, together

with his audience, to the postlude".

I commented on the earlier discs that occasional hints

– a few strained high notes – could be heard of the tumour that was

growing in Schiøtz’s vocal chords. Although these 1946 recordings

were made closer still to the operation which effectively ended his

singing career, I have to say I found the voice in consistently good

form. My other reservation, regarding his use from time to time of a

downward portamento, is still present but worries me less in this more

romantic music. So here is a precious document indeed.

Walter Legge had plenty of projects lined up for Schiøtz,

including much Brahms, whose songs were very poorly represented in the

catalogues then. Alas, all there was time for were these three; a wonderfully

controlled Mainacht, pervaded by the calmness of the warm May

night, an upfront, cholesterol-free Sonntag and a Ständchen

which, though light and humorous, is not too fast to let us hear

the words. And three more Grieg (5 from 1943 were included in Vol. 2).

The two from op. 49 are wonderful songs, Grieg at his richest with piano

parts that look ahead to Debussy. While in A Poet’s last song Schiøtz’s

caressing rubato elevates a piece which could well sound four-square

and banal.

Carl Michael Bellmann was a poet and composer (most

of the melodies are actually folk tunes, and they all sound as if they

are) whose low-life portraits may seem a musical equivalent of Hogarth’s

work in London or the genre painting in nearby Holland. Whether his

work is quite rich enough, judged purely as music, for a non-Swedish

listener to take the trouble to study the translations (which are provided;

Danacord as always give a lesson in presentation to certain major companies)

and therefore appreciate the interaction of words and music, I rather

doubt. Schiøtz must have been fond of them, for earlier versions

of two of these pieces, and of several others, appear in Vol. 5. Even

without knowing a word of Swedish I can detect the clarity of diction

– speech-rhythm and musical rhythm seemingly as one – for which he was

famed.

Considering how attractive Buxtehude can be, I thought

this little cantata a relatively routine piece but, with Mogens Wöldike

at the helm, it gets a performance which stylistically sounds fairly

acceptable even today.

I hope I have made it clear that the lieder on this

CD are absolutely essential listening for all who care about Schumann,

Brahms and the singer’s art.

Christopher Howell