I refer readers to my review

of Vol. 1 of this major series for a brief biographical sketch of

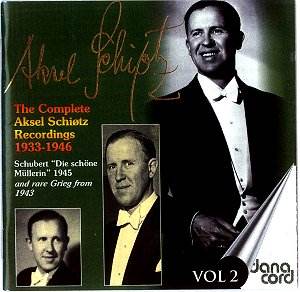

the Danish tenor Aksel Schiøtz. Vol. 2 immediately goes to the

heart of things with one of the major recordings on which Schiøtz’s

reputation stands, the 1945 Müllerin with Gerald Moore.

A recording of this cycle was begun in 1939-40, accompanied

by Herman D. Koppel who, being Jewish, fled to Sweden in 1940. Due to

this and to the Danish people’s understandably strong feelings against

the German language in those years the project, like Schiøtz’s

own international career, was put on hold. Also in 1939, Schiøtz

had recorded the first and eighth songs of the cycle in London with

Gerald Moore so it was entirely apt that in 1945 he was rushed onto

a military aeroplane and became the first singer to sing German lieder

on the BBC after the war. The chosen work was Die schöne Müllerin,

which he then recorded for HMV. The 1939-40 recordings comprise

half the cycle (8 songs with Koppel plus the two with Moore) and are

included in Vol. 4. I hope to compare the different versions in due

course.

Detailed comment is hardly necessary at this stage.

This recording has always represented an ideal for a certain type of

interpretation. Firstly, for the use of a fresh-sounding, light tenor

(the songs are all sung in the original keys), emphasising the youthful

innocence of the protagonist. Secondly, for a basically non-interventionist

approach. Non-interventionist is not a synonym for unimaginative, at

least not in this case; it is sufficient to hear how the singer differentiates

between the several stanzas in the first song. All the strophic songs,

in fact, are worth studying as examples of just what can be done to

vary such pieces by vocal colouring rather than by pulling them about.

The young man’s progress from green innocence to a delusion and despair

with which he cannot cope are charted by vocal and verbal colouring,

without any hint of the hysterical ranting which interpreters of a different

kind have seen fit to apply. The brook’s final lullaby, ironically assuaging

in view of the fact that the damage has now been done, is moving in

the extreme (as a concession to 78 side-lengths, the fourth stanza is

omitted).

Moore for his part provides the ideal backdrop. The

earlier songs are pervaded by the trickling waters of the brook, followed

by apparent calm as the young man ceases his journeying to take employment

at the mill, rising to drama as he realises the girl’s indifference

and moves on again. There has been a tendency of late to take Gerald

Moore too much for granted. He laboured long and well to have the profession

of piano accompanist recognised on the same level of dignity as that

of piano soloist, but more recently it has become common to prefer,

for instance, to Fischer-Dieskau’s records with Moore, later ones using

pianists who are primarily soloists or conductors. Let us remember that

Moore was a great pianist in his own right, and let us reflect what

an art it takes to accompany with equal success such very different

interpreters of the same music as Schiøtz and Fischer-Dieskau.

And let us also remember that the professional accompanist has to be

able to play all this repertoire in a wide variety of keys (I know most

songs are published in at least two keys, but many singers find themselves

most comfortable in another key again). Has the solo pianist ever thought

how much more complicated his life would be if he had to be able to

transpose all his Beethoven sonatas up and down according to the occasion?

Reservations? These are the same as I expressed over

the first volume. Among many high notes which are perfectly placed,

there is an occasional sense of strain. Schiøtz’s vocal chords

were by now compromised by cancer and the operation which would effectively

end his career was only a year off. I shall compare the 1939-40 recordings

from this point of view with great interest. Also, the slight trace

of a downward portamento (hear the first phrase of the brook’s lullaby)

continues not to be to my taste; again, I shall be interested to see

whether this habit is present in his earlier recordings, and to what

extent.

The Grieg songs, recorded for the composer’s centenary,

are put across with much freshness. The op. 33 songs came my way recently

in Vol. 4 of Monica Groop’s survey (BIS-CD-1257). While generally admiring

her singing I queried her tendency to adopt at times a note-by-note

approach where a more legato line might be expected. However, I made

this comment with some diffidence, wondering whether the nature of the

Norwegian language imposed this manner of singing. The notes here comment:

"The Vinje poems are originally in the poet’s own characterful

dialect. Schiøtz sings them in Danish softer grammar." So,

while noting that Schiøtz provides the legato line I missed in

Groop, I still do not know whether she has some linguistic justification

for what she does.

The booklet not only provides much information about

Schiøtz and the recordings, it also includes the singer’s own

detailed comments on how to interpret the Schubert cycle, written in

1970. If you are not troubled by a recording which is obviously not

recent – but the voice reproduces well and the piano, if lacking in

range, is mellow – this recording still has claims to be a first choice.

Certainly, all who care about Schubert and lieder singing should have

it.

Christopher Howell