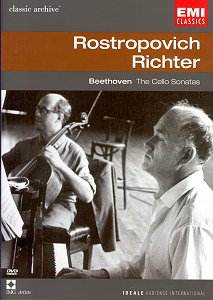

Take two of the twentieth century’s greatest instrumental

soloists, put them together at the service of Beethoven in a live recital,

film it and you get what we have here – an historic musical document

that is both important and inspirational.

This single concert was recorded at the Usher Hall

during the Edinburgh Festival in 1964 and the West was still getting

used to being able see and hear these sensational Soviet artists in

the flesh. Until the late ’fifties they had been virtually locked behind

the "Iron Curtain".

It was an uncompromising recital, starting for some

reason at midnight and consisting entirely of the complete cello sonatas

of Beethoven. Those prepared to stay up late for the event probably

thought, "This is going to be something I can tell my grand-children

about". The audience show their appreciation with prolonged applause

before a note is played. This contributes to a little comedy of errors.

The two mount the platform, Rostropovich carrying his cello, Richter

an extremely dog-eared and heavily sellotaped volume of the sonatas

which he then puts on the piano upside down while the page turning man

starts to fiddle with something at the side of the piano. They sit.

Because the applause will not stop they stand for another bow, getting

tangled with the turning man who is trying to get to his chair. They

sit again. Silence. Then Richter finds his stool at quite the wrong

height so gets up and stands behind it to give the knobs a prolonged

twiddle. Then they start to play and at once we know we are witnessing

something special. A sudden, intense musical concentration takes over

as we are subjected to the beautifully sculptured melodic lines of Rostropovich’s

cello in the opening adagio of the F major sonata followed by the piano’s

announcement of the first subject of the allegro played with that unmatchable

Richterian combination of zip and delicacy.

The recital organised the sonatas in chronological

order which, incidentally, provides us with a sweep from early Beethoven

via middle period to the threshold of late period. The first two sonatas

broke new ground in that they are a genuine dialogue between the two

instruments, the piano elevated from accompanying bit part to virtuoso

partner with the cello. This was new. The last sonata of the evening

(or morning!) matures into what some think the finest of all cello sonatas

culminating in a fugato that sends a message that we are approaching

Beethoven’s so-called third period.

The performances are filmed, as was the way in those

days, with very few camera angles and no fussy panning and zooming to

distract. This helps the viewer to share some of the concentration so

evident on the stage. Here are two artists very much at one although

they cannot see each other – Rostropovich facing the audience, Richter

behind him facing away and sideways. But they play bound with a sure

interdependence, as if attached by some invisible umbilical chord. Occasionally,

at key points, Rostropovich will lean and half glance sideways, and

Richter never looks to his partner, being glued to the music at all

times. I do not know how many times they had played these sonatas before,

although they had recorded them for Philips over the previous three

years. The evidence is that these are highly honed performances, great

ones in which the pair had arrived at a perfect mutual understanding

of each other. There may be interpretative issues that are not to everyone’s

taste, for example there is an occasional approach to tempi that might

sometimes be associated with Richter, that of taking some fast movements

faster than the norm, and some slower ones, slower. But then there are

so many instances of passing moments that one cannot imagine any other

duo matching, for example the profound, quiet stillness of the start

of the great adagio in the final sonata.

As the recital comes to its end after the rigours of

the fugato ending of that last sonata, the players immediately rise

and in what looks to be an expression of joy, satisfaction and mutual

admiration, Rostropovich kisses Richter on the cheek and they bow holding

hands. A lovely little moment in the context of a great recital, all

caught on film that is a privilege to watch.

The DVD’s "bonus" item, Richter playing Mendelssohn’s

Variations sérieuses, was recorded in Moscow two years

later. The film quality is poor and the sound dire, but it is a welcome

curiosity – Richter never recorded the work commercially. It is a piece

that well shows off Richter’s unique brand of virtuosity, power and

delicacy.

John Leeman

![]() Mstislav Rostropovich,

cello

Mstislav Rostropovich,

cello![]() EMI CLASSICS DVB 4928489

EMI CLASSICS DVB 4928489

![]() [128:37]

[128:37]