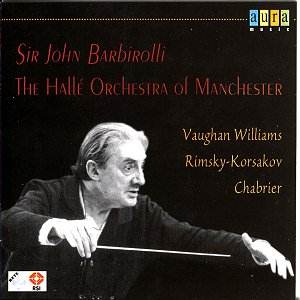

Auraís fine disc catches the Hallé and Barbirolli

on tour in Lugano in 1961. Itís an eclectic concert with Barbirolliís

own Elizabethan Suite and some Spanishry in the form of the Capriccio

Espagnol and Chabrierís España. The main focus of interest however

is the work dedicated to him, Vaughan Williamsí Eighth Symphony.

Firstly the Elizabethan confection, which like his

Purcell Suite is anachronistic (even then) charming and irresistible

in equal measure. Byrd, Farnaby and Bull are the composers whose works

are woven into the Barbirollian tapestry. His efforts were certainly

not as pervasive or as famous as those of his occasionally antagonistic

fellow countryman, Thomas Beecham and his Handelian conflations. But

they are cut from recognisably the same cloth even if Barbirolliís are

less pompous and more obviously pliant. They also remind us of Barbirolliís

place in the scheme of things in the renaissance of sixteenth and seventeenth

century music on record - not least when he was part of André

Mangeotís Quartet in the mid-1920s and recording English chamber music

of this period for Compton Mackenzieís National Gramophonic Society

label (an offshoot of the then newly established The Gramophone

magazine). So in this spirit I was immediately seduced by the string

saturation of the Earl of Salisburyís Pavane and the nobility

and expressive diminuendos Barbirolli imparts. As I was by his vigorous

foot stamps in the Irish ho Hoane Ė lashings of gallantry and

vim here as well. The Kingís Hunt ends the suite Ė hurrying,

scurrying strings and a hilarious muted strings episode that should

raise a smile from even the flintiest of hearts.

Rimsky-Korsakovís Capriccio Espagnol opens with glittering

panache but there is also a lilting gravity in the strings that adds

lustre and depth to the performance. The pizzicati are executed with

precision and clarity, a decisive and unstoppable head of rhythmic steam

thus generated and, dynamically vertiginous, the performance ends in

blazing splendour. España is a six-minute encore of animation

and colour in Barbirolliís hands. The Eighth Symphony was in the Halléís

bloodstream by now and they sound marvellously dramatic here. The vibraharp

emerges with clarity; the cellos sound energised and the violins enter

the Fantasy first movement with passionate sweep. Maybe there are some

ensemble slips here but they pale into insignificance when weighed against

the fervour and animation of the playing and the conducting. The melting

second subject, the hushed intensity generated with what one best call

an intense chastity of sound, are all hallmarks of the Barbirolli string

sound and treasurable examples at that. But Barbirolli marshals the

movement to a close with intense concentration, alive to the complex

evolutionary patterns and mutability of the workís direction. In the

Scherzo alla marcia Barbirolli is adept, as few of his competitors ever

are, at the insouciant humour of the movement. The brass-packed punch,

the off-beat stresses, the idiomatic orchestration; this is every bit

as distinctive and complete a sound world as cultivated by,

say, JanŠček in his own very different brass writing. In the beautiful

Cavatina the weight of string tone and levels of emotive intensity are

wonderful to hear, the rise and falling of the lines accommodated with

perfect touch and timing. Whereas in the Toccata finale Barbirolliís

drive and drama, the swirl and the glitter, the resurgent stentorian

brass are all magnificently aflame. Wonderful stuff.

Barbirolliís commercial Eighth is available on Dutton

in their Barbirolli series CDSJB

1021 coupled with the London. A BBC Legends BBCL

4100-2 has the 1967 Prom performance of the Eighth coupled with

Crown Imperial, the orchestration of Baxís Oboe Quintet, Deliusí Cuckoo

and an acetate of Ferrierís Land and Hope and Glory. But this 1961 Lugano

concert is a most dramatic and persuasively alive performance and the

rest of the concert is brimful with incident and colour and life. No

reservations Ė just acclamation.

Jonathan Woolf