Those new to Nielsen will start elsewhere, since this

composerís brilliantly personal and original exploration of the orchestra

demands to be heard in state-of-the-art sound. The first two symphonies

here have a rather dull sound, much as one might have experienced from

a medium-wave radio set at the time, and the Grøndahl 2 has quite

a lot of wow at the beginning. Nos. 3 and 4 are much more brilliant,

if top-heavy; the 1952 4th is often strident, though timpani definition

is remarkable for the date. The Paris 5th is opaque again and, in contrast

to the Danish audiencesí rapt attention, the atmospheric opening is

compromised by a bronchial barrage way beyond the barrier that divides

lack of self-control from sheer bad manners. The studio recording of

no. 6 is clear but shallow. That said, the ear quickly adjusts to some

enthralling music making, so if you have modern recordings and want

to investigate the work of three of Nielsenís finest interpreters, donít

let my comments put you off.

This set usefully supplements the work of Dutton Laboratories,

who have transferred the HMV and Decca studio recordings by the same

conductors. But the great thing about the Danacord set is that in only

one case did the conductor here record the same work commercially.

Like Sibelius, Nielsen conducted no recordings of his

own music, though his daughters always maintained that no subsequent

conductor matched his own performances. Furthermore, while Sibeliusís

symphonies were all on disc by the end of the 1930s, during the lifetime

of the composer, whose reactions to some of the recordings are known,

the first Nielsen symphony to be recorded came in 1933, two years after

his death. This was a live performance of no. 5 under Georg Høeberg,

now available in Vol. 6 of Danacordís "Historical Nielsen"

series. The same volume also contains what should have been the next

Nielsen symphony on record, a test pressing of no. 2 under Jensen, made

in 1944. This remained unissued until the Danacord transfer.

So exploration of one of the major symphonic cycles

of the 20th Century began in earnest after the war, and it is fortunate

that it was entrusted to three Danish conductors who had been closely

associated with the composer. First off the mark was Tuxen, who recorded

no. 3 for Decca in 1946, followed by Jensenís remake of no. 2 for HMV

in 1947. Still on HMV came the 5th from Tuxen in 1950 and Grøndahlís

4th in 1951. Jensen recorded the 1st for Decca in 1951, followed by

a rival 5th in 1954. All these have been reissued by Dutton Laboratories.

In the meantime Jensen had completed the cycle, recording no. 6 for

Tono in 1952. This recording was made available in Great Britain by

World Record Club in 1960 and is contained in the present Danacord set.

By the time of the stereo era Nielsen had been taken up by international

conductors and orchestras; the 1960s saw recordings by Markevitch (4),

Barbirolli (4), Bernstein (3, 5) and Ormandy (6), leading to a positive

explosion of rival cycles in the 1990s.

The oldest of the three Danish conductors was Launy

Grøndahl (1886-1960). He was the permanent conductor of the Danish

Radio Symphony Orchestra from 1926 to 1956; the recording of the 2nd

symphony included here comes from his farewell concert. Alongside Grøndahl

the youngest of the trio, Erik Tuxen (1902-1957), who had began his

career as a jazz band leader, had been conducting the orchestra regularly

since 1936 and had frequently appeared with it on foreign tours (an

earlier edition of this Danacord set included his 1950 performance of

no. 5 from the Edinburgh Festival; this performance marked the start

of Nielsenís appreciation in Great Britain). He was the logical choice

to succeed Grøndahl yet I have been unable to find out if the

appointment had actually been made before his untimely death.

Thomas Jensen (1898-1963) had founded the Aarhus Symphony

Orchestra in 1935 and remained its conductor till 1957 when he took

up the appointment with the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra. As an orchestral

cellist he had played most of Nielsenís symphonies under the composer

himself and is said to have had a particularly precise memory of his

tempi. The present set includes the only existing tapes of the two symphonies

he did not record commercially, nos. 3 and 4, so the complete cycle

can be heard under his baton.

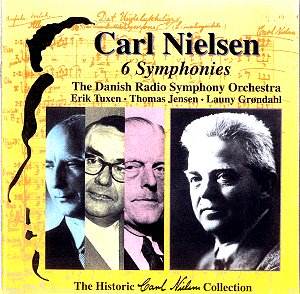

Looking at the photographs of these conductors (included

in the well-documented booklet) it is interesting to reflect whether

an artistís interpretative stance can be guessed from his physiognomy.

In two cases out of three one would say yes, for Tuxen is lithe and

volatile, living dangerously for the moment. He brings a euphoric surge

to Nielsenís remarkable first symphony, galvanising it into life without

neglecting the more lyrical moments. In the fifth I feel he perhaps

fires all his guns too soon, and thus is unable to cap his earlier climaxes

with the final pages. Itís a fine performance, but perhaps the least

exceptional of the six.

Grøndahlís severe, granitic expression, on the

other hand, matches an interpretative approach which seems to survey

the work from on high, taking in all its grand architectural dimensions.

This does not absolutely preclude either vitality or poetry and this

no. 2 has qualities similar to those of the best Boult/Vaughan Williams

performances of the same period.

Jensenís appearance is much more enigmatic. In fact

he is the conductor of the three who seems to shed his own personality

when on the rostrum. When I hear Jensen conduct Nielsen I seem to hear

the voice of the composer, without the interposition of an interpreter.

He finds a little more breadth in the music and gives fullest expression

to its poetic moments. But he can also be electrifying. The third symphony

surges to an overwhelming conclusion, but even more remarkable is the

1952 fourth. From the start he plunges in without pity for his players

and the finale is simply breathtaking; this must be one of the greatest

performances the work has ever received. What an orchestra this was

in those days! Apart from Grøndahl and Tuxenís work with them,

they had the benefit of a long association with Fritz Busch and Nicolai

Malko.

Without an audience to stimulate Jensen, tension is

a notch lower in the sixth. It would be an exaggeration to call it studio-bound,

however, for it is still a fine, vital performance, and the work itself

is in any case not so obviously overwhelming as the others.

For those who want to get under the skin of this music

these recordings are a necessary supplement to the modern cycles.

Christopher Howell