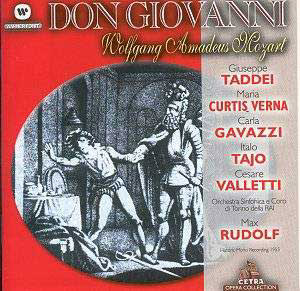

Though Cetra used to be considered valuable above all

for Italian operas that were not otherwise available, this set shows

that at least some of its all-Italian (or nearly so) versions of Mozartís

Italian operas deserve a second look. The more so when we no longer

have to endure Cetra sets in strident sound; this is forward and clear

and equal to practically anything from the same date.

The conductor Max Rudolf was born Max Rudolph in Germany

in 1902, began to work in the German Opera House in Prague in 1929,

emigrated to the USA in 1940 and started his association with the Metropolitan

Opera House in New York in 1945, becoming its artistic administrator

from 1950-1958. In that year he moved to the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra,

where he remained until 1970. There followed three years at the Curtis

Institute and appointments in Dallas and New Jersey. He conducted for

the last time at the age of 90 and died in 1995.

Something of a legend in his adopted country, Rudolf

did not figure much in the major companiesí recording programmes and

his name probably does not mean very much to European listeners. A number

of records made with Cincinnati SO were available on LP in the UK in

the 1970s and failed to make an impression. I suppose you could say

that in the present instance he offers above all clean textures and

a good deal of energy rather than great insights (I certainly thought

this during the overture), but in the opera pit this counts for much.

He sees that the drama unfolds at the right pace and negotiates a labyrinth

of tricky tempo changes in the first act finale without putting a foot

wrong. Many of his tempi are challengingly fast and we should note that,

while the Mozart of many contemporaries who were judged his superior

in their day (Böhm for instance) now sounds heavy, Rudolfís does

not.

Most lovers of this opera will have Taddeiís performance

of Leporello in the famous Giulini set made a few years after this.

They will surely welcome the chance to put his Don alongside it. This

is a Don Giovanni who maintains the veneer of a gentleman and is all

the more dangerous for it. His half-voice in the serenade is a remarkable

piece of vocal control. By his side is Italo Tajo, a skilled practitioner

of small parts on disc over a period of many years. His vocal acting

is excellent and in his scenes with Don Giovanni his rather overbearing,

truculent Leporello sometimes seems to be getting the upper hand. In

their recitatives they really strike sparks off each other; thereís

no match for Italians doing this sort of thing in their own languages.

His actual voice is revealed, especially in the company of Taddeiís

sharply focused vocal production, to be a little cavernous and woolly,

but itís a splendid performance even so.

Cesare Valletti (1921-2000) later sang Don Ottavio

both at the Met and at Salzburg. His way with the part is more openly

passionate than, say, Anton Dermotaís gently besotted lover; itís a

stronger type of voice than we would be likely to use for Mozart today.

On the other hand, any attempt to make Don Ottavio a little less one-sided

as a character than usual is all to the good.

In my recent review of Carla Gavazziís Adriana Lecouvreur

I told what I know about her, and refer readers there. Even taking into

account Taddei, she could be a principal reason for getting the set.

She has character; from the moment she enters her words have

a life that holds the attention. However, you are also warned that this

is a way of singing Mozart to which we are not used today. She unhesitatingly

uses chest tones on lower notes, her vowels are often bitingly brilliant

and she at times applies a rapid vibrato. She throws herself passionately

into the coloratura passages and, while I donít suggest the notes are

not there, itís a far cry from the "string of pearls" concept

of Mozartian passage-work that is more common. For her, also the coloratura

has to mean something. Unorthodox Mozart, but done with such

conviction to make you wonder if her way is not the right one after

all. Though Gavazziís career was curtailed and her records were few,

the evidence is that she was an artist of some importance.

Maria Curtis Verna is the one non-Italian in the cast,

though since she was established in Italy at the time of the recording

she certainly sounds idiomatic enough. Born Mary Curtis, she acquired

an extra Italian surname and Italianised her first name, and was much

admired in Italy for a few years (at about this time she also recorded

Aida, with Franco Corelli, and Un Ballo in Maschera, with

Tagliavini and Valdengo, both for Cetra). After this she returned to

the USA, varied her name again to Mary Curtis-Verna, and appeared regularly

at the Met. I can trace no recordings from her later period. She also

became active as a teacher.

Itís a rich, almost mezzo-like voice. Indeed, certain

signs of strain in the upper register suggest she may actually be a

pushed-up mezzo more than a real soprano, but I must say the coloratura

in Non mi dir is safely negotiated and she is impressive in Or

sai chi líonore. Her style is not always clean, without the compensation

of Gavazziís strong personality, and her vocal production perhaps relies

on volume more than perfect focus. She is the weakest link in a strong

cast, but is by no means to be dismissed.

Elda Ribettiís main claim to fame is that she sang

Oscar in the 1943 Ballo in Maschera with Gigli and Serafin. She

has a soubrettish voice, but with more body than usual for this sort

of part and gives a strong performance. I can find no information about

Vito Susco but this is an acceptable Masetto, and once again he and

Ribetti really know how to make the recitatives fly off the page.

Antonio Zerbini (1924-1987) offers a good Commendatore

without the last ounce of massive authority needed to drive the climatic

moment home.

It hardly need be stated at this stage that the above

information does not come from the booklet which, as is the way

with these Cetra reissues, offers an introductory note, in Italian and

English, and the libretto in Italian. Regarding the performers, the

merits of Taddei are extolled, which most of us know anyway, but nothing

is offered on the more elusive ones. We do get photos of all of them,

however.

With so many important versions of Don Giovanni

in the catalogue I suppose this is not exactly a first choice, but

it adds up to more than the sum of its considerable parts and if it

did happen to be the only one on your shelf youíd get all the right

ideas about the opera. Opera buffs will want it for Taddei, Valletti

and the little recorded Carla Gavazzi.

Christopher Howell

see also review

by Robert J Farr