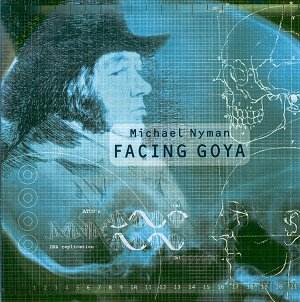

How you respond to Facing Goya will almost certainly

depend on how much you like Michael Nyman’s brand of minimalism. As

the person usually credited with coining the term (at least in a musical

sense) he has, over a period of some twenty-five years, forged what

has now, rather ironically, become known as ‘post-minimalism’. What

this means in pure listening terms, I’m not quite sure (maybe it’s just

critics, who do love ‘tags’). What is certain is that if you are familiar

with almost any of his other scores, particularly the film scores for

Peter Greenaway, you will know what to expect. And you will get it -

in abundance.

What may trouble some people more is the story, a rather

curious, time-travelling concoction that tries hard to address serious

issues (genetics, cloning, racism), but constantly gets bogged down

in its own cleverness. Broadly speaking, it takes as its starting point

the dis-interment of the painter Goya’s headless body in 1888, and uses

a thriller-like narrative to take us on a search, back and forth in

time, for the missing skull. It ends with the discovery of the skull

and the subsequent attempt to clone the artist. All this may seem rather

sci-fi-like, but the deeper point is (according to the composer) that

the opera is a meditation on "the way scientists, geneticists,

politicians and artists use measurement to exclude, coerce and control

others". Some may detect a link here with his chamber opera of

1986, the Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat, and that neurological

case study does have similarities with Facing Goya. But the big

difference is that the previous opera worked, theatrically and on disc.

It had a taught construction, was concise in length and had a musical

texture that had a lightness and transparency not always evident in

his brasher scores. Goya is too long for its material, and Nyman’s

‘pop crossover’ tendencies are very much to the fore. Thus the opening

Prelude, a quite atmospheric, slowly lilting introduction, is followed

by Dogs Drowning in Sand, a pounding ‘aria’ that will either

grab you enthrallingly, or have you biting the carpet in frustration.

Actually, it reminded me somewhat of the wonderful opening counter-tenor

song At Last the Glittering Queen of Night, from The

Draughtsman’s Contract. But where Nyman’s Purcell-like canons and

pulsating ground basses fitted Greenaway’s artificial Restoration world

to perfection, here it simply goes on too long and gives the singers

a hard time trying to scream over it. The instrumental scoring is also

extreme-Nyman, with his characteristic amplified saxophones and solo

fiddles dominating the ensemble texture. In fact it occurred to me,

as I struggled to stay the course, that the musical structure is not

only based on repeated patterns within a single section, but the entire

opera seems made up of slowed down or speeded up versions of two or

three basic patterns. I know that is a fundamental principal of minimalism,

but Nyman really does seem to get away with murder in places.

The other big problem is his refusal to engage emotionally.

His music hardly ever allows for this, and it doesn’t particularly matter

much in most of the film scores he’s picked. But here I had the feeling

that he should pull back, give the listener respite, and maybe allow

his characters to identify with their situations. Of course, as with

much modern theatre, the multiple role-playing used here hardly encourages

this concept, and the overall effect is of a Brechtian alienation, or

emotional distancing, from the plight of the characters. It is possible

that the staging, which was originally at Santiago de Compostela, would

have helped resolve these issues, but the aural experience alone does

not help to assess the score sympathetically.

The singing is presumably what the composer intended

(the cast are all Nyman regulars) and does involve extremes of range

and pitch, virtuosic certainly, but so mechanical and steely-toned as

to be hardly an entirely pleasant listening experience. The work has

already come in for some hostile criticism; BBC Music Magazine found

it ‘cheap and cheerful … with numbingly repetitive rhythms and progressions

which make the common chord truly common’. Nyman fans will not be troubled

by this, and will probably already have the set. For those who, like

me, have been intrigued by his particular sound world for some years,

there simply may not be enough variation, or feeling that the composer

has moved on, to sustain real interest. The booklet is handsomely produced,

with essays by the composer, a critic and a doctor, all making a case

for the subject. I understand the set is medium-priced, which may help,

but one is left with the nagging sense that this really is for aficionados

only.

Tony Haywood