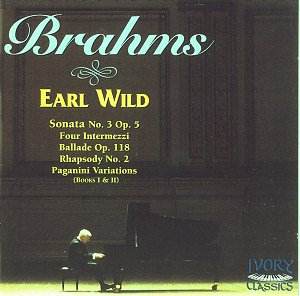

Earl Wild has been a legend for longer than most of

us have been alive; here we have a brand new version of the massive

and taxing third sonata, recorded in his 87th year, a selection

of shorter pieces from two years earlier, and a 1982 live performance

from Paris of the Paganini Variations.

When we think of Wild, the picture in our mindís eye

is that of a keyboard wizard of the old school, one who combines a phenomenal

technical control with a touch of dare-devil "I do it my way".

After all, he has been something of a specialist in works and transcriptions

by composer-pianists of the early 20th Century romantic school

Ė remember his recording with Erich Leinsdorf of one of the Scharwenka

concertos at a time when such music was sneered at. And he looks the

perfect patrician virtuoso wizard. I remember him giving a concerto

in Edinburgh in the early 1970s Ė donít ask me which, it may even have

been the Scharwenka Ė and more than any musical phrase I recall the

visual image of his tall, erect figure (a very straight back) despatching

hair-raising passages with, apparently, total nonchalance. He hardly

seemed to be putting any effort into it at all! In this only Horowitz

surpassed him. I also remember the extreme clarity of his sound which

registered in the back rows almost as if he were only a few feet away.

Though he has been recording since 1937 he has not

been quite a household name on disc. He has not consistently been associated

with one company, like Rubinstein-RCA or Arrau-Philips and some of his

discs, such as the Rachmaninov concertos with Horenstein, came out almost

by stealth (as a Readersí Digest album) and remained unknown for many

years. We have also not had very many opportunities to hear him in extended

works, like the present Brahms sonata, from the general repertoire.

He now records for Ivory Classics and they deserve to make each othersí

fortune.

As befits a pianist in the old-school-virtuoso mould,

"Earl Wild plays Brahms" is definitely "Earl Wild plays

Brahms". If you listen to the recording of the sonata by the admirable

Stephen Hough on Hyperion, you will quickly sit back and find you are

listening to Brahms. At the end you will be grateful to Hough for playing

Brahms so well, but the interpreter is not forever present. I donít

want to suggest that Wild twists the music this way or that according

to his personal whims, in fact he doesnít. But in the same way as Horowitz

would frequently give performances with no detectable deviation from

the score, yet which proclaim his own personality in every bar, so it

is with Wild. Compare the way he begins with that of Hough; there is

something in the sound, so bright and spot lit in every note, something

in the phrasing, imperious and commanding our attention, something maybe

in the timing of rests, of the transition from one idea to the next.

And "Earl Wild plays Brahms" is an enthralling experience,

undimmed by his advanced age. Listen to how the scherzo leaps into life,

or how the textures of the finale are illuminated, or how the melodic

strands in the Andante espressivo are separated out from the accompanying

figures. The final climax of this latter movement put me in mind of

a story about Heifetz, who was berating a student for producing too

little tone at the climax of the Chausson Poème. "You

will be lost under the orchestra". A friend present at the lesson

intervened: "But, Jascha, the violin always is lost under

the orchestra at that point". But Heifetz would have none of it.

Unconvinced (with other violinists the violin was always drowned

at that part of the music) the two could only wait till the next time

Heifetz programmed the piece. And, sure enough, his powerful tone dominated

the whole orchestra. In the same way, Wild has the upper line in the

texture soaring over the rich textures in a way that most of us tend

to think a piano just canít do. Thatís great pianism.

The shorter pieces are equally spot-lit and up-front,

purged of the autumnal melancholy traditionally associated with them.

In at least a few cases I felt that Wildís own bright optimism was at

odds with Brahmsís natural melancholy (might not op.119/3 sound more

teasing at a fractionally slower tempo, and does not op. 76/6 surge

when it should reflect?), but it is salutary to hear them this way once

in a while. Only in op. 79/2 did I seriously feel that Wild was missing

the sheer blackness of one of Brahmsís most tragic and angry utterances.

The Paganini Variations are unique in Brahmsís work;

unique in their exploitation of a sheer virtuosity worthy of the violinist

who inspired them. Wild makes light of them in a marvellous display

of light and shade as well as of infallible technique that rightly evokes

cheers (and the French are inclined not to be lovers of Brahms). This

1982 recording also reminds us that the greatest pianists are harder

to record than the merely good ones. The "ping" to their tone

(Iíve heard Wild use this word in an interview), which is the means

by which they reach the back of the hall, can sound aggressive, even

bashy, under the close-up glare of the microphones. It does a little

here, but donít let that put you off. And in the recent recordings it

has at last proved possible to capture a great pianist without discomfort.

The sound has remarkable richness and presence. Comparison with the

Hough, as admirably recorded as it is played, shows this up too.

You wonít always want to hear Brahms played this way,

but if you care about the composer, or about the piano, youíve got to

have this.

Christopher Howell