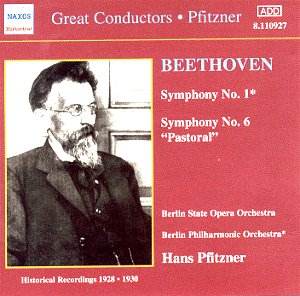

To mark the centenary of Beethoven’s death English

Columbia released a raft of prestigious recordings, amongst them the

complete symphonies with a number conducted by the august Felix Weingartner.

In Germany Grammophon released its own competing series – parcelled

out to Pfitzner, Richard Strauss, Oscar Fried and Erich Kleiber – but

unlike Columbia’s, Grammophon’s series (often to be found on its Polydor

export series) wasn’t to be completed until a tardy 1933. Pfitzner undertook

the recording of the lion’s share, with five symphonies to his credit.

It’s often overlooked that he had a distinct career as a conductor –

in Strasbourg amongst other places – and in certain respects at least

seems to have been considered as accomplished a Beethoven conductor

as the more internationally successful and known Weingartner. Pfitzner’s

virtues were very much those of the subjective German school: tempo

fluctuations, moulded string sonorities, affectionate wind choirs, a

flexible tempo rubato, considerable weight of "bass up" string

tone and in relation specifically to his recording career a pervasive

use of the rallentando to mark side breaks. This was a constant feature

of many artists’ recordings in the 78 era and has always seemed to me

at least as significant a distortion of performance practice as the

much more commonly explored area of tempo – and the rushing adopted

(or not) to accommodate a piece of music onto a 78 side. One can hear

the rallentando on several occasions here – and it was a musical solution

to an unmusical problem, if for us now perhaps something of a difficulty

to reconcile within the context of a given tempo or variance from it.

These 1928-30 Polydor recordings (Polydor was the German

Grammophon Company’s export label) are difficult precisely to date but

have been well transferred by David Lennick, albeit the originals are

definitely inferior to the slightly earlier Columbia series made in

London. Equally they show Pfitzner in both spirited and spiritual engagement

– and also on occasion as a slightly less successful practitioner. The

First Symphony receives much the less compelling reading and not merely

because of the relative standing of the two works. There’s a curious

sense of detachment throughout much of the symphony – not indifference

exactly, but rather more as if Pfitzner had less need or desire to devote

weight of impress upon it. Rob Cowan, sleeve-note writer, calls it "stylistically

unexceptional" and it’s true that whilst there is, from time to

time, a certain affectionate profile the work as a whole is rather disappointingly

underplayed.

Contrast the Pastoral, which clearly engaged

Pfitzner to a very considerable degree. There is some cavernous lower

string moulding in the first movement, with quite splendid cellos and

a sense of continuum and flux. The elasticity is generated at quite

a slow tempo and those rallentandos are particularly noticeable here;

note as well the very heavily and italicised shaping of the wind choir’s

responses to the strings. The second movement is again romantically

and indeed pictorially beautiful, with Pfitzner never holding back from

encouragement of his wind principals whilst allowing them sufficiently

flexible tempi to allow them to phrase with sometimes idiosyncratic

freedom. The scherzo is quite slow but the fourth movement is powerful

and taut whilst the finale, though once more slow, has a flexible, subjective

and incremental power that I find enormously persuasive.

The Pastoral was one of the best, if not the

best, of Pfitzner’s Beethoven cycle; full of insight, affection and

detail it repays study, both in terms of what he saw in the symphony

and in terms of conducting practice generally.

Jonathan Woolf

![]() Berlin Staatsoper

Orchestra [No 6]

Berlin Staatsoper

Orchestra [No 6] ![]() NAXOS 8.110927 [63.50]

NAXOS 8.110927 [63.50]