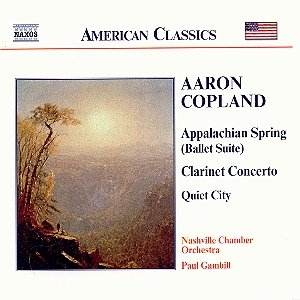

That Aaron Copland is regarded as the quintessential

American composer is completely justified by the inclusivity of his

output. There is no other composer from the United States that better

represents the make-up of the American people in his music. Educated

in Europe, well traveled in Latin America, and the inventor of what

he dubbed the American vernacular style of composition, Coplandís works

express the diversity of his native land. His legitimization of both

the folk and jazz idioms by bringing them to the "classical"

concert hall is a contribution that would affect a number of his fellow

composers, Leonard Bernstein being the most notable among them.

What a find we have here in the Nashville Chamber Orchestra

and its exemplary lineup of soloists. An adolescent amongst performing

ensembles, this mere twelve-year-old stands out as an orchestra of maturity

and virtuosity. Active in the vital arena of the performance of music

by living composers, Paul Gambill and his band have commissioned and

premiered more than two-dozen new works. (Nota bene big five: this little

orchestra in the south is putting all of you to shame in the "music

of our time" department.) One can certainly hope that the worldwide

distribution might of Naxos will garner a great deal of attention for

this outstanding organization.

Nothing is more satisfying to a critic than to hail

a fine program, interestingly planned and excellently executed. And

that is exactly what we have here for the price of a combo meal at the

local fast food joint. Letís start off with the orchestral works. The

Three Latin American Sketches began life as two brief individual

pieces that the composer dismissed as unworthy of the concert repertoire.

It was not until André Kostelanetz commissioned a third piece

in 1971 that Copland revived his two earlier works, putting them together

in a suite ripe with the rhythm and color of Latin America. Played here

with verve and panache, these three minor scores make for a delightful

concert opener.

Appalachian Spring was written in 1944 for Martha

Grahamís dance troupe. This was the work that was to make Copland the

first American composer to gain international recognition. The music

went on to win both a Pulitzer Prize and a New York Criticís Circle

award, and is widely regarded as the finest example of Copland Americana

style of composition. The performance here is clean, sparse and elegant,

with just the right amount of nuance and a very appropriate lack of

sentimentality. The opening melancholy string passages are beautifully

hushed, and the faster rhythmic passages are precise and clear. The

Simple Gifts solo is played to perfection.

There are not sufficient superlatives to heap upon

soloist Laura Arden for this spectacular rendition of the concerto for

clarinet. Commissioned in 1947 by none other than Benny Goodman, the

great jazz man nearly let his exclusive rights to performance of this

work expire before he finally got up the nerve to play this fiendishly

difficult work in public. Of course, he did play the piece and recorded

it many times, twice with Copland himself conducting. This performance

is sheer perfection. Divided into two main sections, the concerto is

played without pause and is a tour de force for the solo instrument.

Opening with a long and mournful melody, Ms. Arden verily weeps through

her instrument, and one is lost in the beauty of both the tune itself

and her playing. There follows a monster of a cadenza and a fast movement

that is pure jazz with an orchestral accompaniment. Pushing the instrument

to the extremes of its range without a moment to breathe, Arden rips

through this incredibly difficult solo with a childís ease. She is a

world-class talent, and we hope to hear more from her soon!

Finally, we come to this writerís very favorite Copland

work, the achingly beautiful Quiet City. Paula Engerer and Scott

Moore are wonderfully expressive in their sedate and lonely solo passages.

Everything is in its place in this performance and one could not ask

for a better-balanced rendition. Everything that the composer wished

to depict in this picturesque score is brought to the fore, painted

on a broad canvas with exquisite colors and the finest of brushes.

Recorded sound is near perfect with a warm reverberant

acoustic and an excellent balance between the instruments and between

soloists and the orchestra. Viola Rothís program essay is concise, informative

and well structured. Recommended without a momentís hesitation.

Kevin Sutton