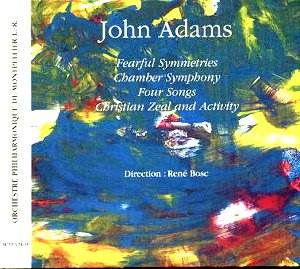

Adams with a Languedoc accent. I’m not quite sure why I was

surprised to see those combustible pieces Fearful Symmetries and the Chamber

Symphony played by the Orchestre Philharmonique de Montpellier – after

all the Lyon Opera Orchestra is hardly a stranger to Adams’ music on record

– but I do admit to a certain curiosity when I saw that the Four Songs

and Christian Zeal and Activity were also on the programme. Zany motoric

propulsion is one thing but how would these French forces cope with the

Baptist certainties of the latter and the gospel and jazz-pop saturation

of the first three songs let alone the rock star guitar heroics of Earthquake?

In the end my fears – scepticism, call it what you will – were pretty

much misplaced.

In an attractive book format with cream coloured pages

and an encomium from the composer himself the French-only notes set

the scene. Let’s get the technicalities over with here; I wish I could

decipher Actes Sud’s CD release numbers. This is the second one in a

row that has taxed my powers beyond breaking point. I hope the number

above is correct but some persistence may be in order because there

are several numbers and a barcode scattered throughout disc and booklet.

You could also try OMA34102. Back to the music. The disc opens with

Fearful Symmetries, that motoric intensifier with its vocalized saxophones

and their human cries. The constant lifting and lightening of the instrumental

textures is realized here with superior skill – those instrumental suspensions,

ingenuous build-ups and releasing of orchestral tension as ever splendid.

The Montpellier orchestra is especially successful in its reaching of

the decisive apex of the piece before the coda of rippling and glacial

treble-orientated writing. The sense of almost absorbed abstraction,

still quiveringly alive, but reaching its by now natural span is gorgeously

– if that’s not too florid a word for the intensely interior experience

– maintained. Perhaps it took a French orchestra to concentrate my mind

on the matter but that coda does have something spatially Gallic about

it.

The Chamber Symphony, one of the great American works

of the last twenty years, was composed in 1992. The marvelous sonorities

of Mongrel Airs, the first of the three movements, the vitality of the

writing and the orchestral colour are vivid and dazzling. There are

moments of drum madness, skittering violins and insistent, manic woodwind,

driven as if by a force of nature. Lest one underestimate it there is

also a sense of the sophisticated and dangerous insistence of cartoon

music throughout much of Mongrel Airs that will later resurface with

decisive finality in the last of the three, the unambiguously titled

Roadrunner. The Aria with Walking Bass second movement opens with an

air of solemnity that becomes increasingly cauterized by eddying fiddles

and absurd orchestral interjections. The bass line meanwhile continues

its now half hidden obscured passage, as if indifferent to the aural

perversity surrounding it. Its dignity is the dignity of a chorale prelude,

assailed but not overthrown by the incessant activity and abrasion around

it. Finally the madcap antics of Roadrunner. Tuned jazz percussion clip

and flip their way through this monstrous burlesque; huge rabble rousing

excitement and the variety and vitality of lurid cartoon colours. It’s

like the Revue de la Cuisine gone berserk. Just as one expects still

more mayhem the solo violin perks up, dusts himself down, slips into

a tuxedo and indulges in a virtuosic cadenza straight out of the nineteenth

century canon. All fall silent except for a tambourine, astonished by

this strange turn of events, as well they might. Adams toys with one’s

expectations with triumphant assurance.

The Four songs derived from I was looking at the

ceiling and then I saw the sky occupy still stranger stylistic ground.

A gospel harmony trio with jazz piano comping vie with a rocking gospel

rip roarer; a pop tinged vamped chords charmer is followed by a tricksy

electronic heavy rock guitar solo, complete with feed back and the whiff

of cordite and the reek of lank, unwashed locks. Christian Zeal and

Activity features the stentorian Emmanuel Djob in full Preacher mode.

This is simpler stuff but full of concentrated power, repetitious certainly

in the manner of such sermons, but reaching full power through an accumulation

of different verbal emphases and rhythms. To that extent it’s stylistically

the opposite of, say, Gavin Bryars’ Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet,

which takes a hymn and repeats it in a loop with subtly changing orchestral

backing.

Clearly directed more at the Francophone market this

is a disc not to be ignored. It scoops up some prime Adams in fine performances,

adds some eclectic flavouring and serves it up in imaginative and committed

performances. I needn’t have worried and nor should you.

Jonathan Woolf